- Mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy had heavier infants and mothers who lost weight during pregnancy had lighter infants.

- Mothers who gained less weight (particularly <15 pounds) and who lost weight during their pregnancy had increased risk of a low-birth-weight infant (under 5 lb 8 oz).

The relationship between gestational weight change and newborn weight is complex, but many studies provide evidence that greater maternal weight gain during pregnancy is associated with higher infant birth weights (1). This pattern is complicated by the fact that individual mothers have highly variable weight trajectories over the course of their pregnancies. Further, nausea and vomiting due to morning sickness, especially in the first trimester, can lead to temporary weight loss during the early stages of pregnancy. Studies have shown that maternal weight gain in early pregnancy is associated with higher newborn birth weight (2, 3), whereas weight loss during this period—often due to morning sickness—has been linked to lower birth weight (2). We previously explored the relationship between maternal weight loss and gain during pregnancy.

Although recommendations for gestational weight gain differ based on pre-pregnancy BMI category, for most mothers it is only recommended to gain 1-5 pounds in the first trimester (4). Although weight loss may occur in the first trimester, it is generally considered concerning only when it exceeds 5-10% of the mother’s pre-pregnancy body weight (4). Performing accurate studies with longitudinal weights is challenging, and survey-based studies of weight change during pregnancy are often limited by recall bias (3). To address this, we relied on observational data collected at the point of care throughout the pregnancy.

Building on our previous report of maternal weight gain, we were curious to further understand the correlation between maternal gestational weight change and infant birth weight. You can also view this entire study, including methodology, definitions, and the full analysis, directly within Truveta Studio.

Methods

We included a cohort of mothers with linked children within Truveta Data, as we previously described. We captured the first live birth event for pregnant mothers aged 18-50 years who had a linked child and delivery date between January 2019 – August 2025. Mothers with diagnostic codes associated with preterm births and non-singleton births were removed from the analysis.

Methods for calculating maternal weight change are described in our previous report. For infant weights, extreme values (under 3 lbs 5 oz or over 13 lbs 4 oz) were excluded due to the possibility of data errors, or an underlying health condition of either mother or infant contributing to the extreme weight.

We explored the relationship between infant birth weight and gestational weight loss and gain, stratified by the mother’s obesity status, as well as associations by race and ethnicity. Secondly, we classified infants weighing less than 5 lbs 8 oz as low-birth-weight newborns (5). We looked at the probability of a low-birth-weight newborn based on gestational weight loss and gain, including stratification by mother’s obesity status.

Results

Population

We included 117,752 pregnant mothers and their linked infants, who were born between January 2019 and August 2025. Demographic and weight gain/loss factors of mothers is described in our previous report. 57,711 (49%) of infants were female, and 59,975 (51%) were male. The average newborn birthweight was 7.2 pounds.

Total weight gain and newborn weight

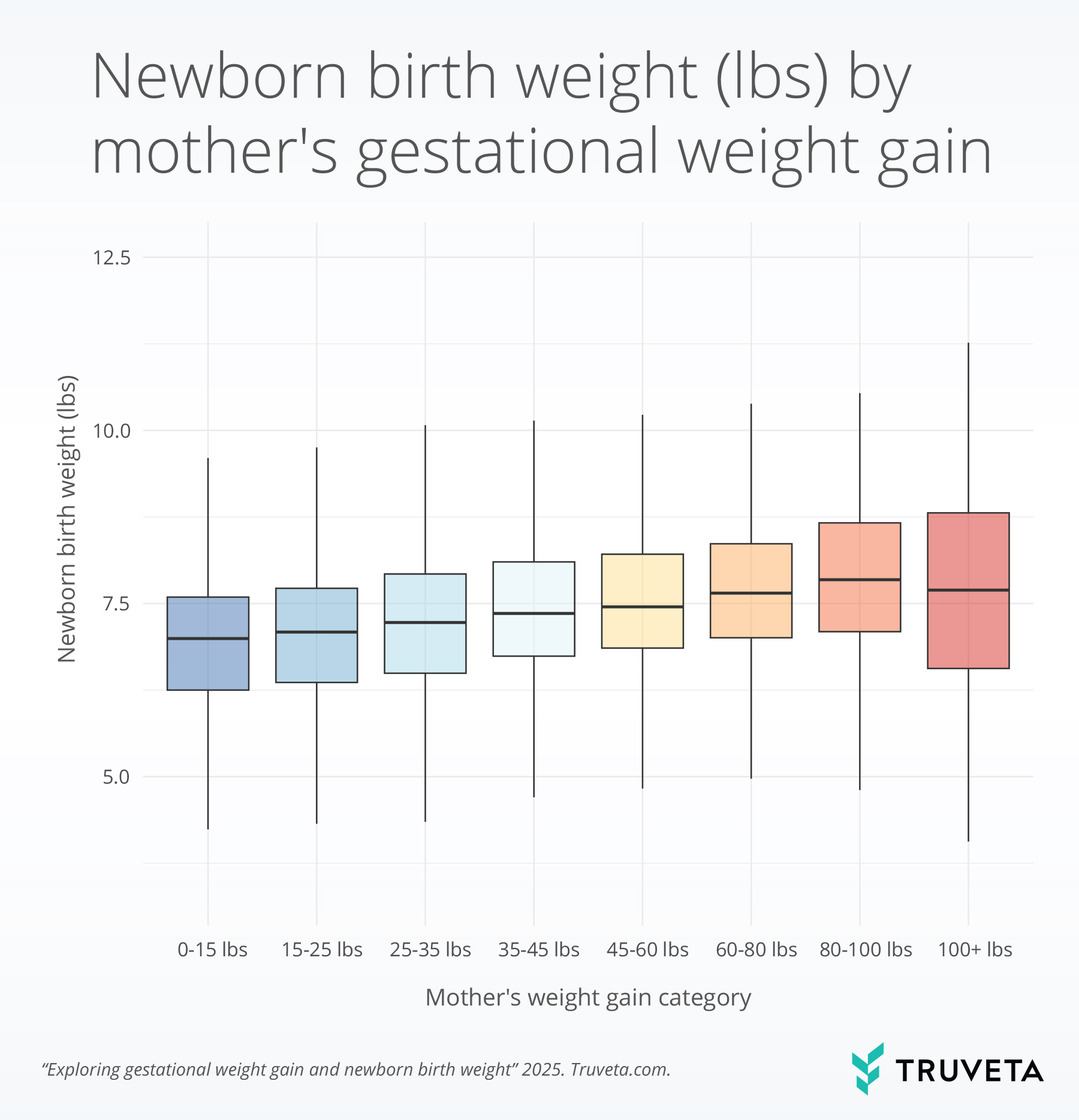

We observed a positive association between mother’s weight gain during pregnancy and newborn birthweight, where mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy had heavier babies. Median infant weight increased with maternal weight gain: infant weight was 7.0 lbs for mothers who gained 0–15 lbs, 7.4 lbs for mothers who gained 35–45 lbs (5.7% heavier), and 7.8 lbs for mothers who gained 80–100 lbs (11.4% heavier).

The below boxplot shows newborn birth weight by maternal weight gain. The line inside each box represents the median weight gain (or the 50th percentile). The bottom and top of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentile. Together the vertical space inside the box represents the middle half of all women. This is known as the interquartile range. The whiskers, or thin lines extending from the box, show typical lower and higher values, reaching up to 1.5 times the height of the box.

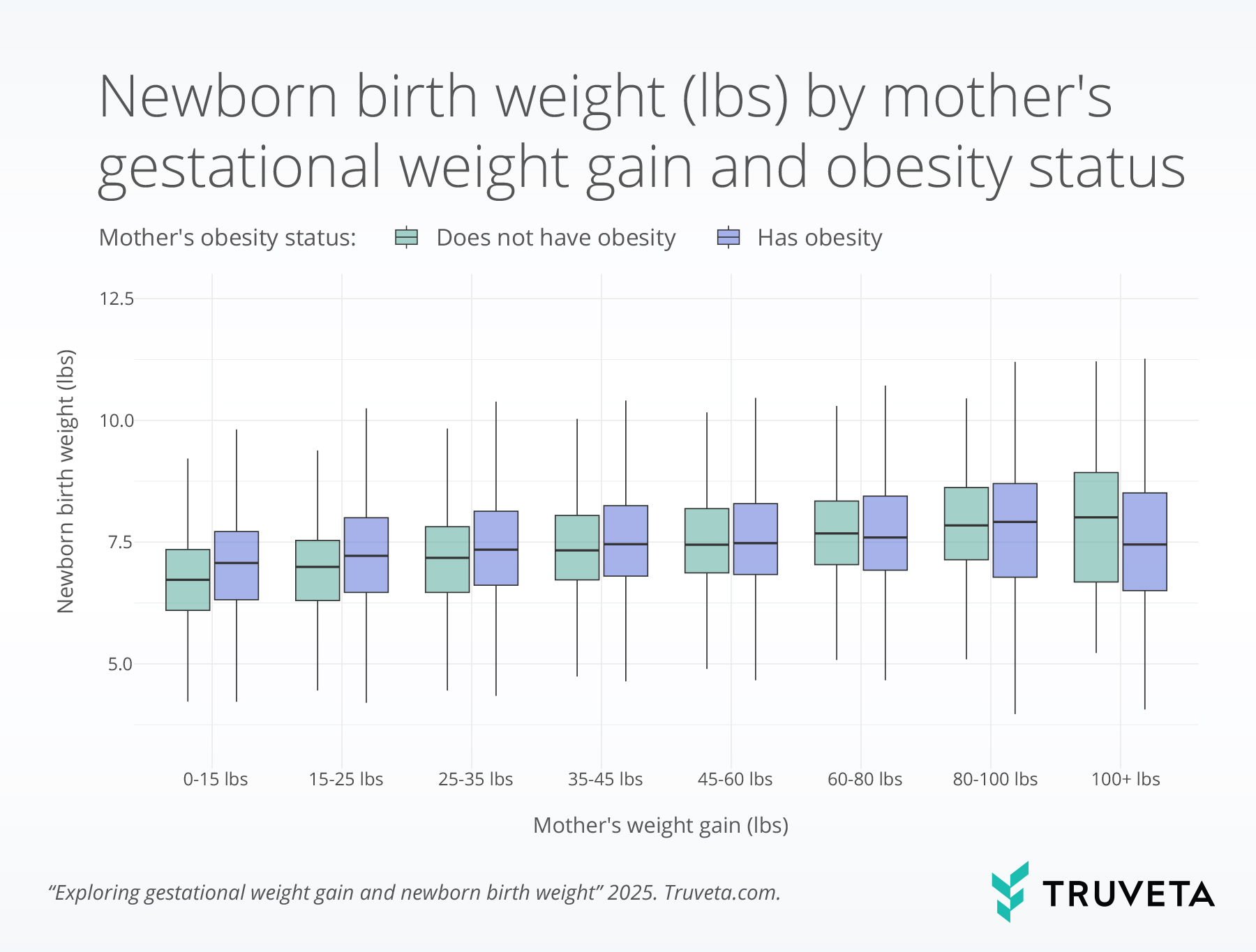

When we compared mothers with and without obesity before pregnancy, we found that for the same amount of weight gained during pregnancy (below 60-80 pounds), mothers with obesity tended to deliver heavier newborns. This difference was especially pronounced when mothers gained only a small amount of weight, suggesting that pre-pregnancy obesity is linked to higher newborn weight even when gestational weight gain is relatively low. However, for mothers who gained 100 pounds or more, the pattern reversed: newborns of mothers with obesity had lower birth weights compared to mothers without obesity.

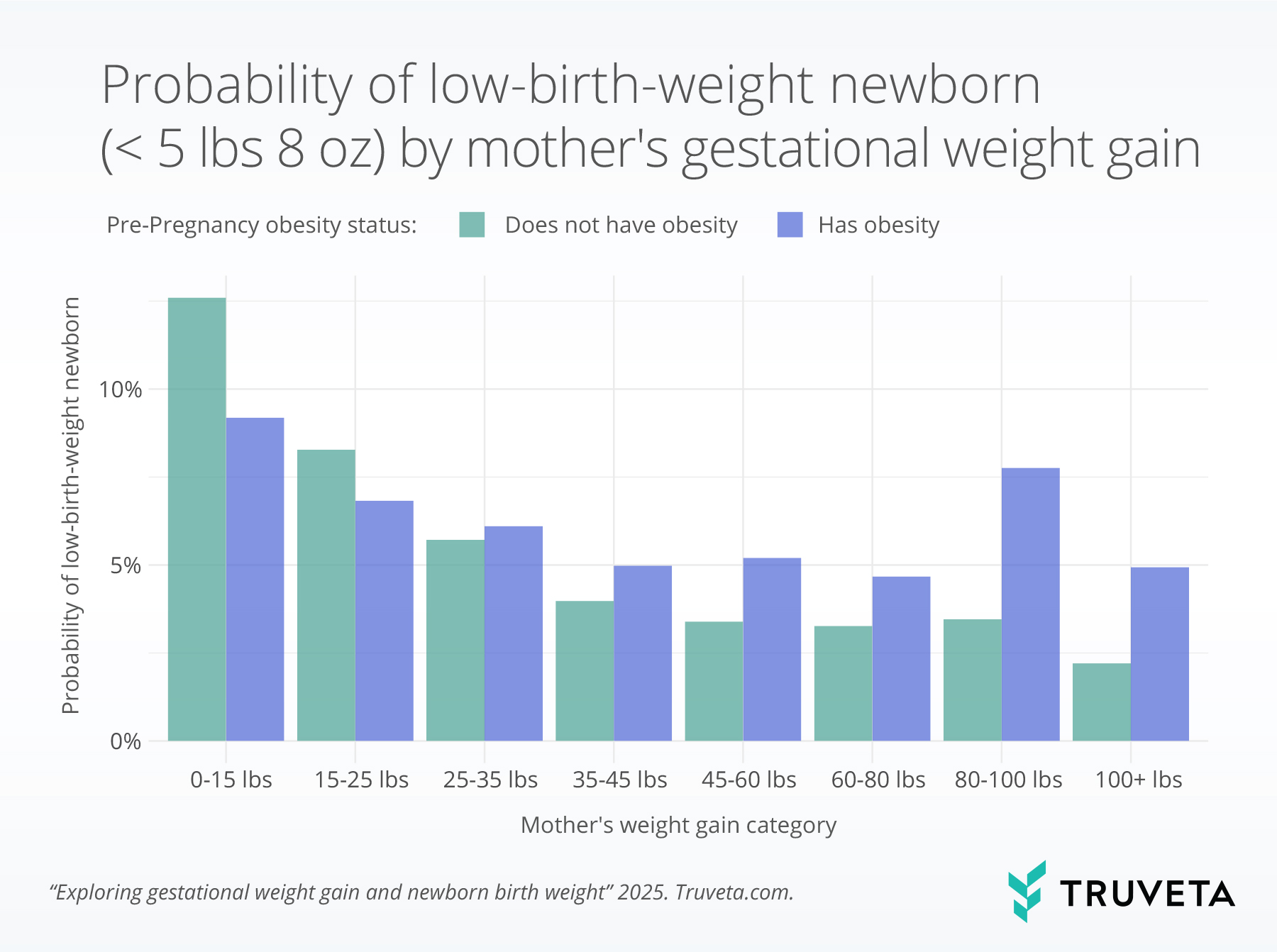

Stratifying by pre-pregnancy obesity status, we saw that mothers who gained 0-15 pounds had the highest chance of delivering a low-birth-weight newborn: 12.6% for mothers without obesity and 9.2% for those with obesity. In general, the risk of low birth weight decreased as gestational weight gain increased. However, among mothers with obesity, the trend shifted for those who gained more than 80 pounds; mothers who gained 80-100 pounds had a higher chance (7.8%) of delivering a low-birth-weight newborn.

Total weight loss and newborn weight

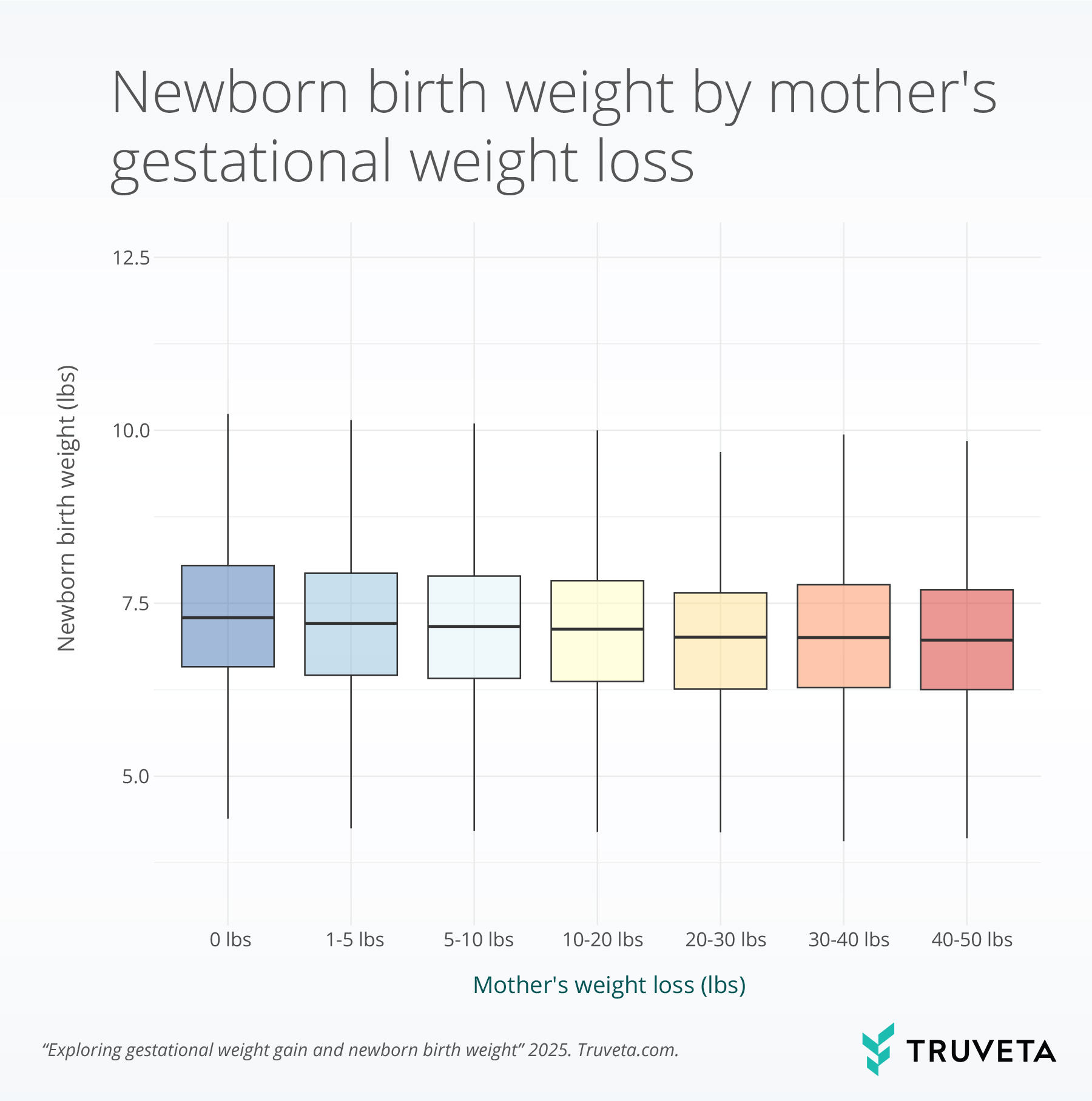

We saw more modest associations between mother’s weight loss during pregnancy—meaning her weight fell below her pre-pregnancy level—and newborn weights. Mothers who did not lose any weight during pregnancy had a median 7.3-pound baby, while mothers who lost 10-20 pounds during pregnancy had a median 7.1-pound baby, and those who lost 40-50 pounds during pregnancy had a median 7.0-pound baby (a 4.1% lower birth weight than those who lost no weight during pregnancy).

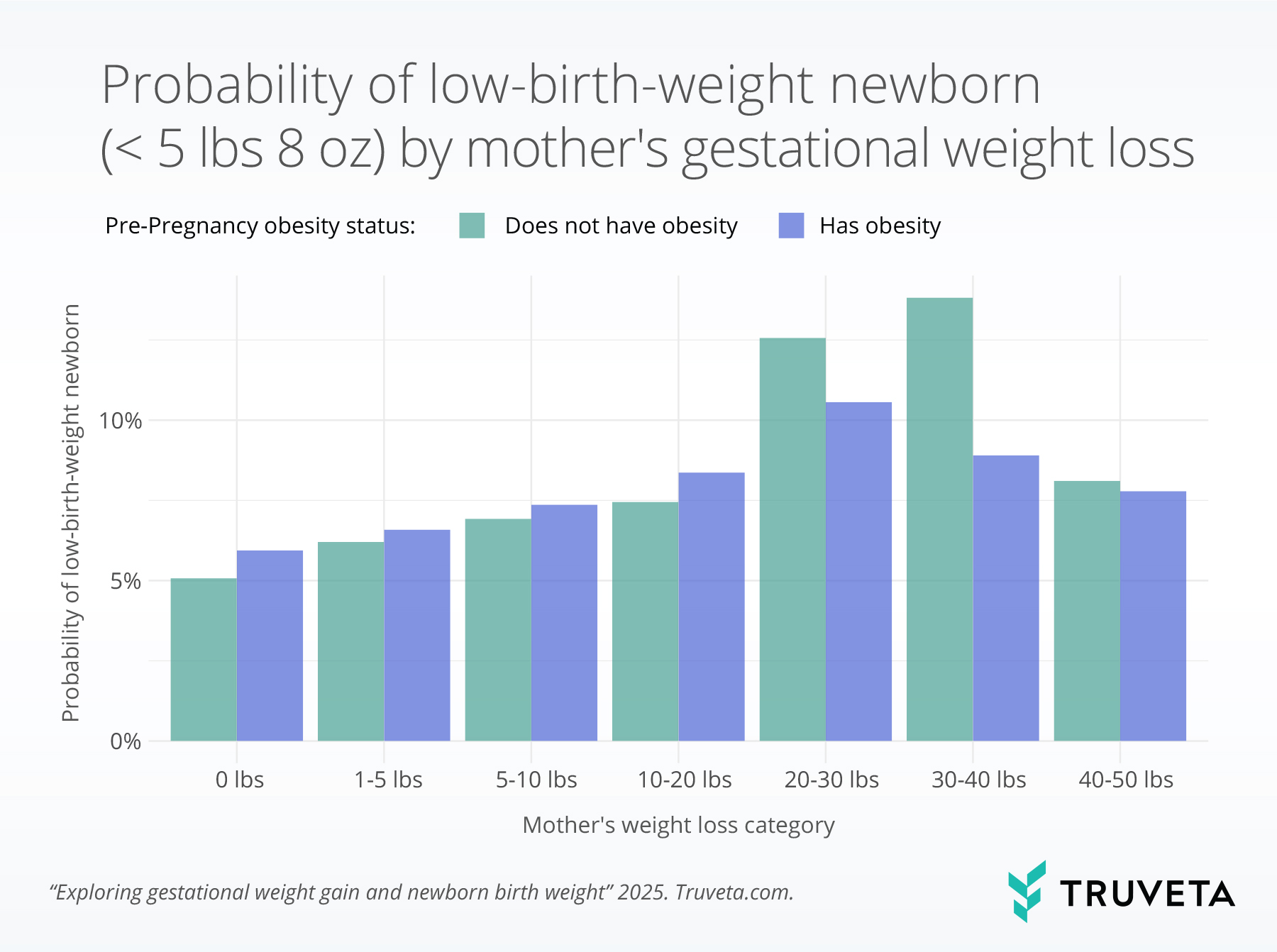

Among mothers without obesity and who did not have recorded weight loss during pregnancy, 5.1 out of every 100 newborns were born with low birth weight, compared to 5.9 out of every 100 newborns among mothers with obesity and no weight loss during their pregnancy.

Among mothers who experienced weight loss, this risk increased—mothers without obesity who lost 30-40 pounds during their pregnancy had a 2.7-fold increased risk of having a low-birth-weight infant as those who lost no weight.

Among mothers with obesity, those who 20-30 pounds during pregnancy had the highest risk of a low-birth-weight infant, a 1.8-fold increase compared to those who lost no weight during pregnancy, but the risk decreased with even greater weight loss.

Discussion

When linking newborn weights to maternal weight trajectories, we saw that mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy had larger babies on average. This matches evidence from the literature from large cohort and cross-sectional studies that found positive, direct effects between gestational weight gain and increased newborn weight (1, 6). We also found an average newborn birthweight of 7.2 pounds across our study, a figure which closely matches the WHO average birthweight of 7.1 – 7.3 pounds for female and male babies, respectively (7).

We also observed that mothers with recorded weight loss during their pregnancy had smaller babies, on average. Few studies (8, 9) have looked at recorded weight loss during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, and any resulting impact or association on newborn weights. Maternal weight change early in pregnancy is thought to influence fetal growth in several ways, including differences in energy intake that affect how many nutrients are available to the fetus, as well as the way fat is stored in early pregnancy and later mobilized to support fetal growth as the pregnancy progresses (8). Studies have found conflicting results on whether mothers who lost weight in early pregnancy had a significantly higher risk of delivering infants who were small for their gestational age (8, 9).

Weight loss during pregnancy has been studied more extensively in populations with obesity, where studies have found that weight loss (over the course of the full pregnancy) was associated with increased risk of small-for-gestational age infants, (10) but can also have benefits, reducing the risk of cesarean section or a large for gestational age infant (11–13).

On the other end of the spectrum, studies have explored extreme weight loss (>15%) among mothers with hyperemesis gravidarum, a serious condition that can lead to hospitalization due to severe nausea and vomiting, and found a significant association with low-birth-weight infants (14). Ultimately, more research is needed to better understand the associations between weight loss during pregnancy—particularly in the first trimester—and resulting impacts on newborn weight.

We explored the probability of a low-birth-weight infant based on maternal gestational weight gain and observed that mothers who gained less weight (specifically those who gained 15 pounds or less) had higher probability of having a low-birth-weight infant, matching numerous studies that have shown that weight gain below gestational weight guidelines is associated with lower birth weight babies (15, 16). We also saw that mothers who lost weight during pregnancy had increased probability of a low-birth-weight infant, again in concordance with literature findings (15).

This analysis has several limitations. Many factors influence both maternal weight changes during pregnancy and newborn weights. Comorbidities and high-risk conditions of both mother and infant, such as gestational diabetes, placental disorders or genetic disorders, likely to have an impact on newborn weights. This analysis did not take such comorbidities into account and thus is unable to evaluate any causal associations.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on September 5, 2025.

Citations

- J. A. Hutcheon, O. Stephansson, S. Cnattingius, L. M. Bodnar, K. Johansson, Is the Association Between Pregnancy Weight Gain and Fetal Size Causal? Epidemiology 30, 234–242 (2019).

- J. E. Brown, M. A. Murtaugh, D. R. Jacobs Jr, H. C. Margellos, Variation in newborn size according to pregnancy weight change by trimester1,2,3. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 76, 205–209 (2002).

- R. Retnakaran, S. W. Wen, H. Tan, S. Zhou, C. Ye, M. Shen, G. N. Smith, M. C. Walker, Association of Timing of Weight Gain in Pregnancy With Infant Birth Weight. JAMA Pediatr 172, 136–142 (2018).

- How much weight should I gain during pregnancy? https://www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/ask-acog/how-much-weight-should-i-gain-during-pregnancy.

- What Is Considered Low Birth Weight?, Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24980-low-birth-weight.

- R. J. C. P. Lima, R. F. L. Batista, M. R. C. Ribeiro, C. C. C. Ribeiro, V. M. F. Simões, P. M. Lima, A. A. M. da Silva, H. Bettiol, Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and birth weight in the BRISA cohort. Rev Saude Publica 52, 46 (2018).

- World Health Organization, Weight for Age Standards. https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards/weight-for-age.

- I. Diouf, J. Botton, M. A. Charles, O. Morel, A. Forhan, M. Kaminski, B. Heude, Specific role of maternal weight change in the first trimester of pregnancy on birth size. Matern Child Nutr 10, 315–326 (2012).

- J. R. Niebyl, Clinical practice. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 363, 1544–1550 (2010).

- E. M. Widen, A. R. Nichols, L. Harper, A. Cahill, J. N. Davis, S. F. Foster, R. R. Rickman, F. Xu, M. M. Hedderson, Weight Loss, Stability, and Low Weight Gain during Pregnancy among Individuals with Obesity: Associations with Adverse Perinatal Outcomes: An Observational Study. Am J Perinatol 41, 1577–1585 (2024).

- Weight Gain During Pregnancy | ACOG. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2013/01/weight-gain-during-pregnancy.

- S. Potti, C. S. Sliwinski, N. J. Jain, V. Dandolu, Obstetric outcomes in normal weight and obese women in relation to gestational weight gain: comparison between Institute of Medicine guidelines and Cedergren criteria. Am J Perinatol 27, 415–420 (2010).

- M. Blomberg, Maternal and neonatal outcomes among obese women with weight gain below the new Institute of Medicine recommendations. Obstet Gynecol 117, 1065–1070 (2011).

- M. S. Fejzo, B. Poursharif, L. M. Korst, S. Munch, K. W. MacGibbon, R. Romero, T. M. Goodwin, Symptoms and Pregnancy Outcomes Associated with Extreme Weight Loss among Women with Hyperemesis Gravidarum. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 18, 1981–1987 (2009).

- R. F. Goldstein, S. K. Abell, S. Ranasinha, M. Misso, J. A. Boyle, M. H. Black, N. Li, G. Hu, F. Corrado, L. Rode, Y. J. Kim, M. Haugen, W. O. Song, M. H. Kim, A. Bogaerts, R. Devlieger, J. H. Chung, H. J. Teede, Association of Gestational Weight Gain With Maternal and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 317, 2207–2225 (2017).

- X. Liu, H. Wang, L. Yang, M. Zhao, C. G. Magnussen, B. Xi, Associations Between Gestational Weight Gain and Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study of 9 Million Mother-Infant Pairs. Front Nutr 9, 811217 (2022).