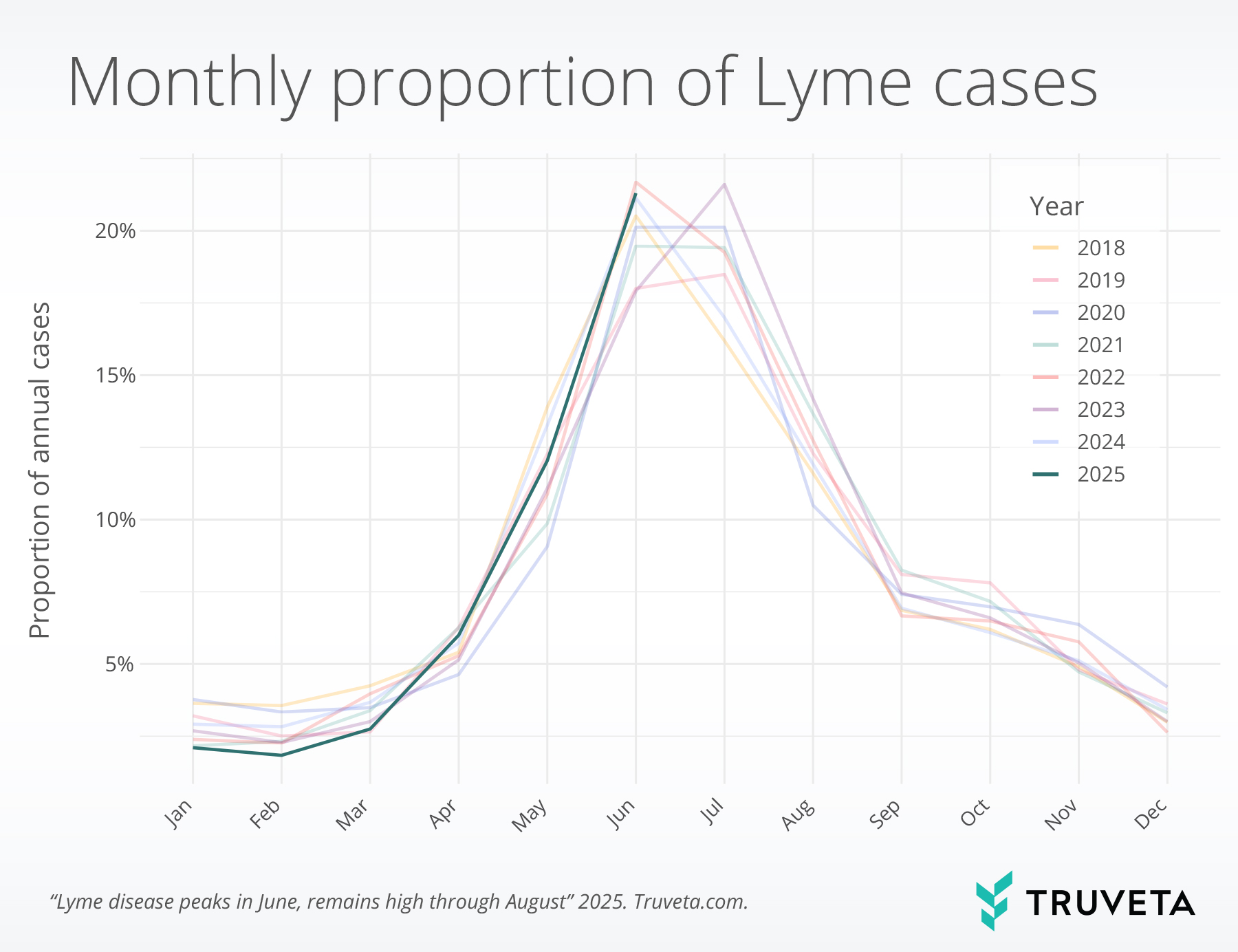

- 62.7% of Lyme cases occurred between May and August, underscoring the heightened risk during late spring and summer.

- June consistently showed the highest activity, accounting for nearly 1 in 5 cases (19.4%) across observed years.

- Risk of Lyme remains elevated in August, historically more than 1 in 10 cases occur this month, even as overall cases begin to decline heading into fall.

Lyme disease, caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, is transmitted through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks, also known as deer ticks (1). It is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States and is endemic in specific regions, particularly in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic, and upper-Midwest regions of the US . Though a notifiable disease, estimates of Lyme disease incidence vary between sources, with CDC reporting nearly 90,000 cases in 2023, while a claims-based study found nearly 500,000 were diagnosed and treated for Lyme a year (2, 3). This likely reflects differences in how cases are diagnosed and recorded and may include patients treated empirically based on clinical suspicion, even if they do not meet strict diagnostic criteria.

Treatment typically involves antibiotics, which are highly effective when administered early. If left untreated, Lyme disease can lead to a range of complications, including fever, the traditional “bullseye” rash, facial paralysis, arthritis, and in some cases, cardiac or neurologic involvement (4). Lyme disease follows a well-established seasonal pattern, with most diagnoses occurring between May and August. Lyme incidence peaks in June and July—when nymphal blacklegged ticks are most active and people spend more time outdoors (5–7). With this seasonal context in mind, we were curious to use Truveta Data to tell us where we are in the cycle this year.

Methods

We used a subset of Truveta Data to identify patients who had been diagnosed and for Lyme disease (henceforth referred to as Lyme cases) between January 2018 and June 2025. Lyme disease was defined as an encounter with a diagnosis of Lyme disease, accompanied by a prescription or dispense of an antibiotic used to treat Lyme disease within 14 days of diagnosis (8, 9).

To better capture new cases of Lyme disease rather than ongoing management, we included only the first diagnosis per patient within each calendar year and required diagnoses to be at least six months apart (9).

For each month within the study period, we calculated the percentage of Lyme cases that month relative to all Lyme disease cases in that calendar year. To account for only having partial data in 2025, we used historical data from 2018–2024 to estimate the typical full-year distribution of Lyme cases. We then scaled the 2025 data to show the percentage of cases by month, accounting for the fact that the year is only partially complete.

We also describe the time to treatments for patients with Lyme disease and the type of treatments they received.

You can view the entire study—including data definitions and code—directly within Truveta Studio.

Results

Seasonal trends

Lyme disease cases showed strong seasonal patterns, with 62.7% of cases occurring between May and August each year. This pattern was consistent across all the years observed, with cases increasing sharply in the spring, peaking in June at 19.4%, and declining by the fall. August accounted for 12.3% of annual Lyme cases in historical data.

Treatment pathways

Among those who received an antibiotic within 14 days of diagnosis, most received that antibiotic very quickly: 91.5% received the antibiotic within three days of diagnosis. Doxycycline was the most commonly used treatment, received by 83.8% of patients overall. Among patients under eight years old, 74.7% received amoxicillin.

Discussion

Lyme disease cases demonstrate clear seasonal variation, with the majority of cases occurring between May and August. This pattern aligns with existing data and previous research showing that Lyme disease tends to peak during late spring and summer, when tick activity is highest and outdoor exposure increases (7, 10). Notably, our findings show that more than one in ten Lyme cases occur in August, indicating that risk remains elevated even after the early summer peak. These findings reinforce the importance of seasonal awareness, usage of insect repellent, and performing tick checks to mitigate Lyme disease risk, especially during the months when risk is known to be elevated (1, 11). Continued vigilance into late summer may be particularly important in Lyme-endemic areas.

In this report, most patients received timely treatment following Lyme disease diagnosis, with nearly all receiving antibiotics within three days. Doxycycline was the predominant therapy overall. However, among children under eight, amoxicillin was the most frequently used antibiotic, and treatment was typically initiated within a day of diagnosis. These treatment patterns are consistent with clinical guidelines, which recommend initiating antibiotics within 72 hours of diagnosis and using amoxicillin for children under the age of eight (12).

There are a few limitations with this analysis. First, this analysis only included people who had evidence of both Lyme disease and subsequent antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease. This may result in undercounting patients who were diagnosed but not prescribed antibiotics within the observed window, such as those treated outside a Truveta member health system or through over-the-counter interventions. In Lyme-endemic areas, it is common clinical practice to treat based on clinical suspicion without laboratory confirmation. Accordingly, these estimates are grounded in treatment patterns that reflect real-world care in such settings, rather than a gold standard diagnosis (13). Finally, while we adjusted 2025 estimates based on historical data, the partial year of available data could still introduce uncertainty in the current year’s trends, should they diverge from historical patterns.

As Lyme continues to expand into new regions, access to timely, high-quality, longitudinal data is critical for public health response (14). Having access to -time data are essential to track emerging trends in diagnosis and treatment, assess adherence to guidelines, and identify opportunities to improve care delivery across populations and regions.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on July 31, 2025.

Citations

- CDC, About Lyme Disease, Lyme Disease (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/about/index.html.

- K. J. Kugeler, A. M. Schwartz, M. J. Delorey, P. S. Mead, A. F. Hinckley, Estimating the frequency of Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerging infectious diseases 27, 616 (2021).

- CDC, Lyme Disease Surveillance Data, Lyme Disease (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/data-research/facts-stats/surveillance-data-1.html.

- CDC, Signs and Symptoms of Untreated Lyme Disease, Lyme Disease (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs-symptoms/index.html.

- CDC, How Lyme Disease Spreads, Lyme Disease (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/causes/index.html.

- J. C. Burtis, P. Sullivan, T. Levi, K. Oggenfuss, T. J. Fahey, R. S. Ostfeld, The impact of temperature and precipitation on blacklegged tick activity and Lyme disease incidence in endemic and emerging regions. Parasites Vectors 9, 606 (2016).

- P. Mead, A. Hinckley, K. Kugeler, Lyme disease surveillance and epidemiology in the United States: a historical perspective. The Journal of infectious diseases 230, S11–S17 (2024).

- K. Nagavedu, K. Eberhardt, S. Willis, M. Morrison, A. Ochoa, S. Soliva, S. Scotland, N. M. Cocoros, M. Callahan, L. M. Randall, C. M. Brown, M. Klompas, Electronic Health Record Data for Lyme Disease Surveillance, Massachusetts, USA, 2017–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 30, 1374–1379 (2024).

- A. M. Schwartz, K. J. Kugeler, C. A. Nelson, G. E. Marx, A. F. Hinckley, Use of Commercial Claims Data for Evaluating Trends in Lyme Disease Diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 27, 499–507 (2021).

- K. J. Kugeler, E. Scotty, A. F. Hinckley, S. A. Hook, C. C. Nawrocki, A. M. Nikolai, A. M. Linz, J. Meece, A. M. Schotthoefer, “Epidemiology of Lyme disease as identified through electronic health records in a large midwestern health system, 2016–2019” in Open Forum Infectious Diseases (Oxford University Press US, 2025; https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article-abstract/12/2/ofae758/7945120)vol. 12, p. ofae758.