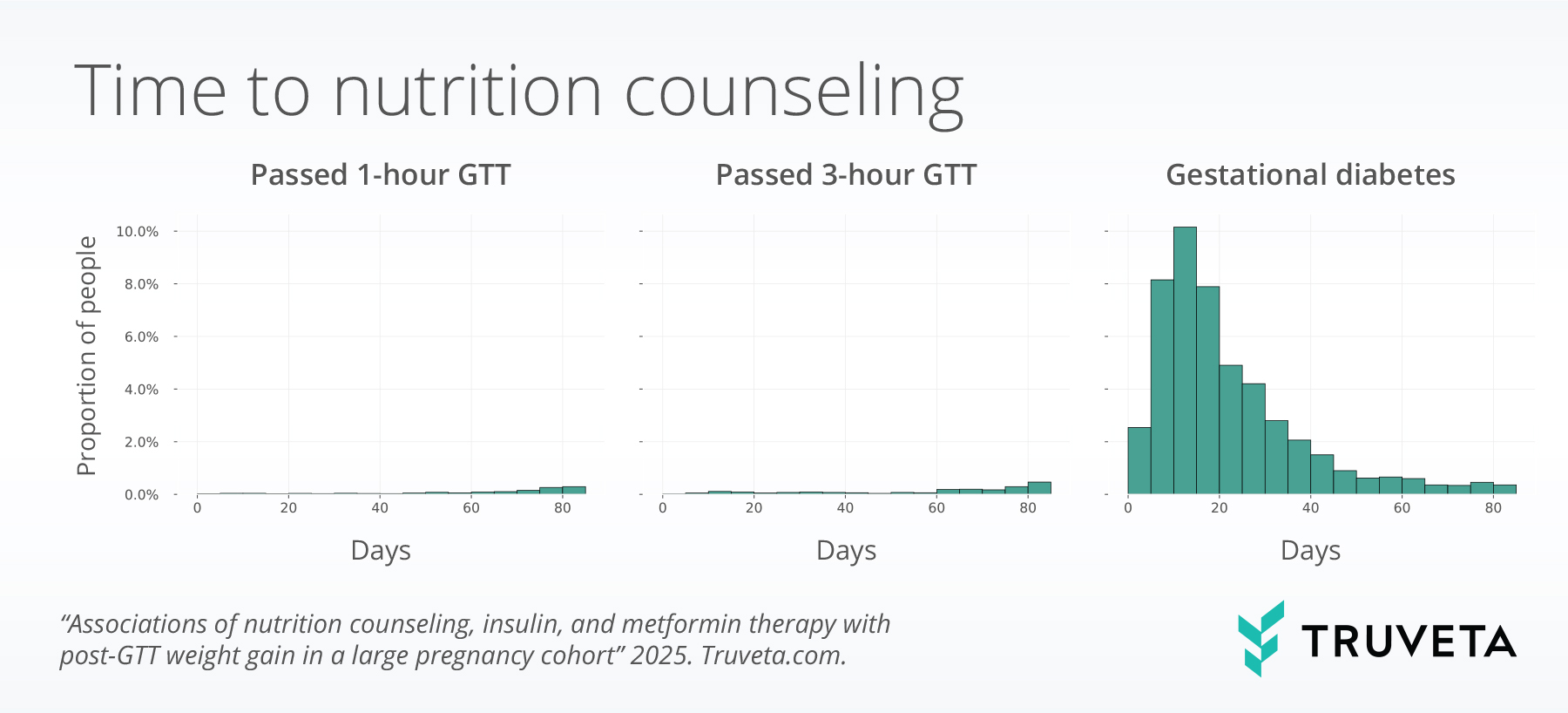

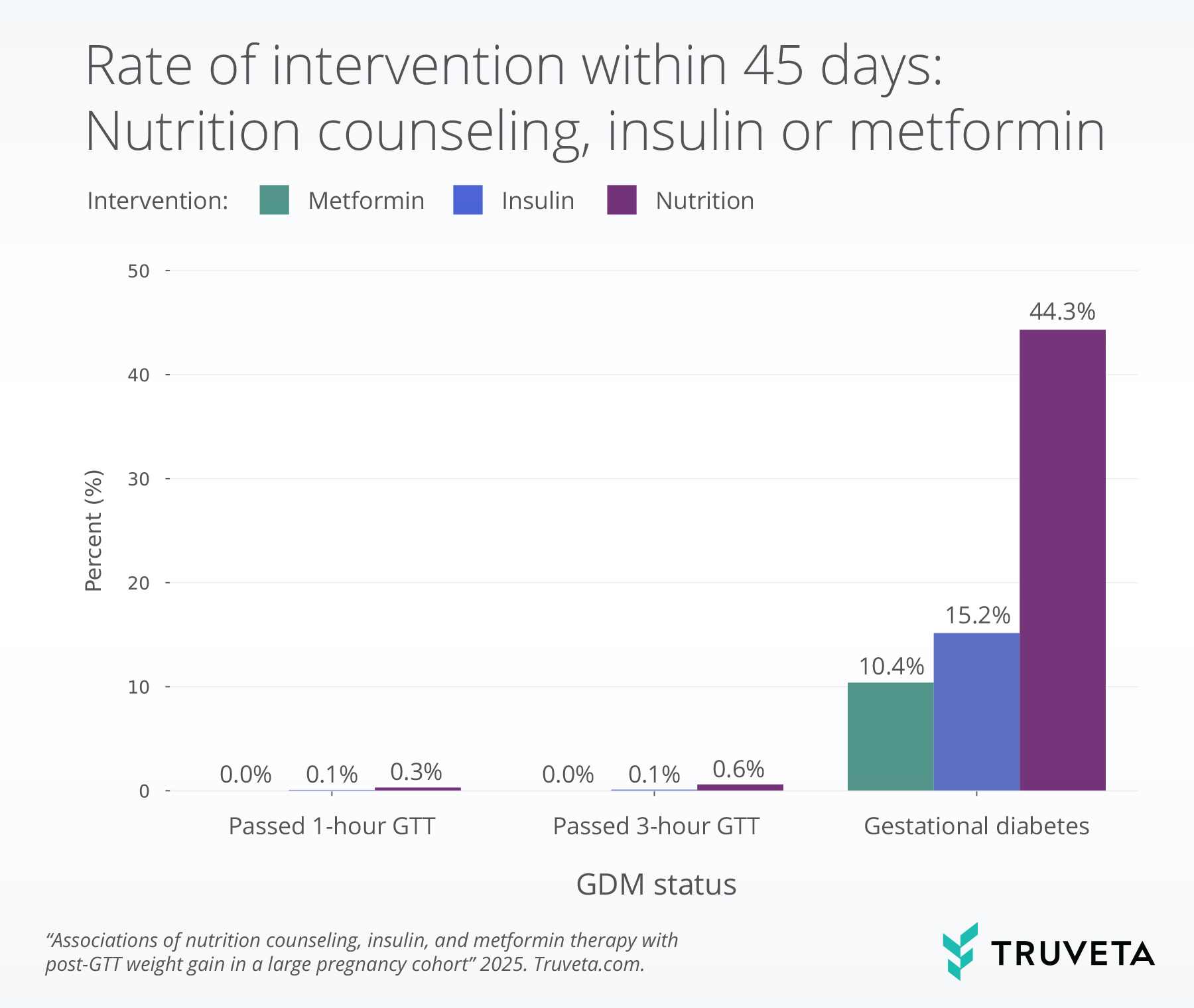

- Nearly half of patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) received nutrition counseling within 45 days of diagnosis, while smaller proportions initiated insulin (15%) or metformin (10%). Despite being the first-line intervention, about half of patients with GDM did not receive counseling.

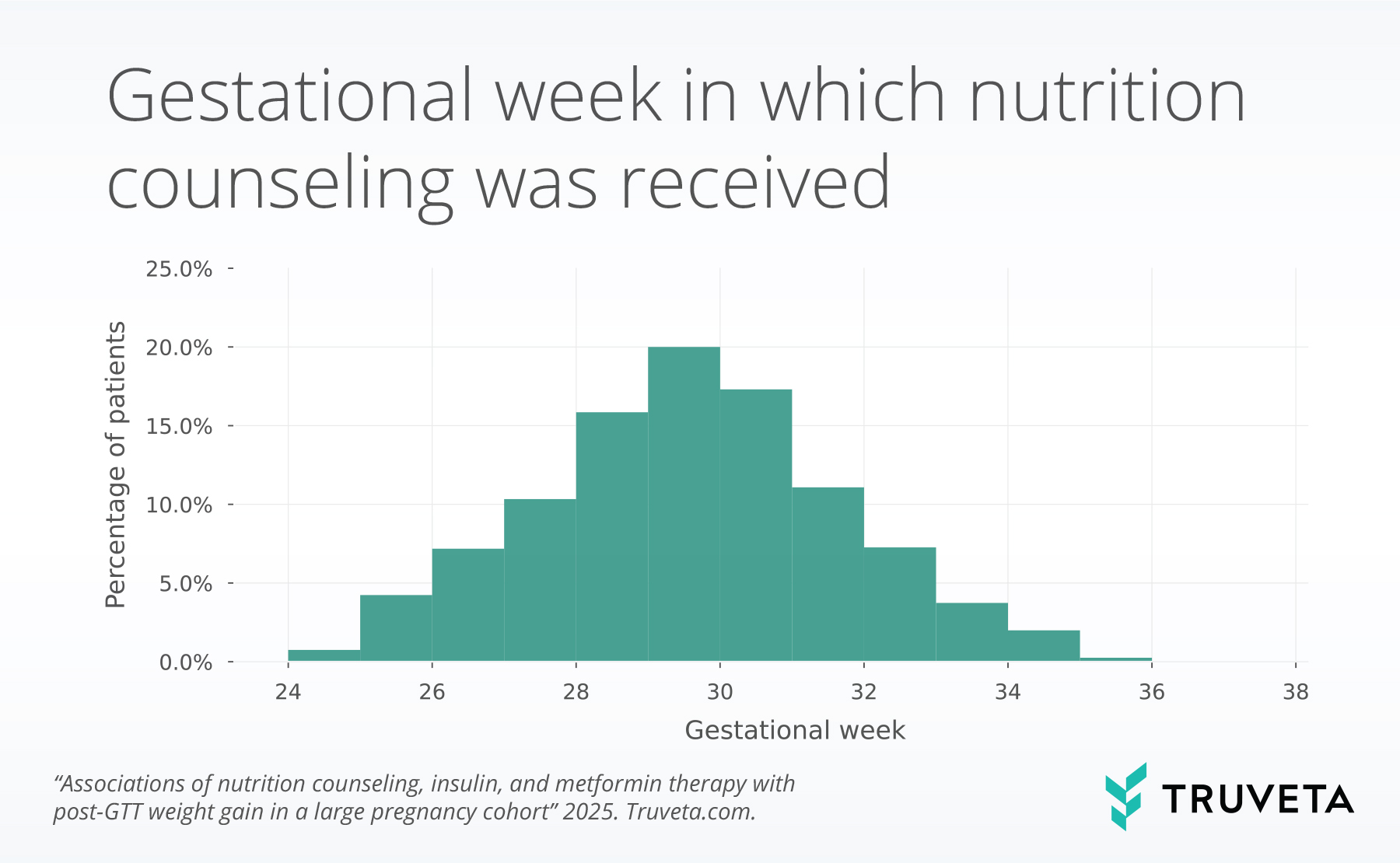

- Among those who received counseling, 2 in 5 began at or after 30 weeks gestation, suggesting potential opportunities to improve timely intervention after diagnosis.

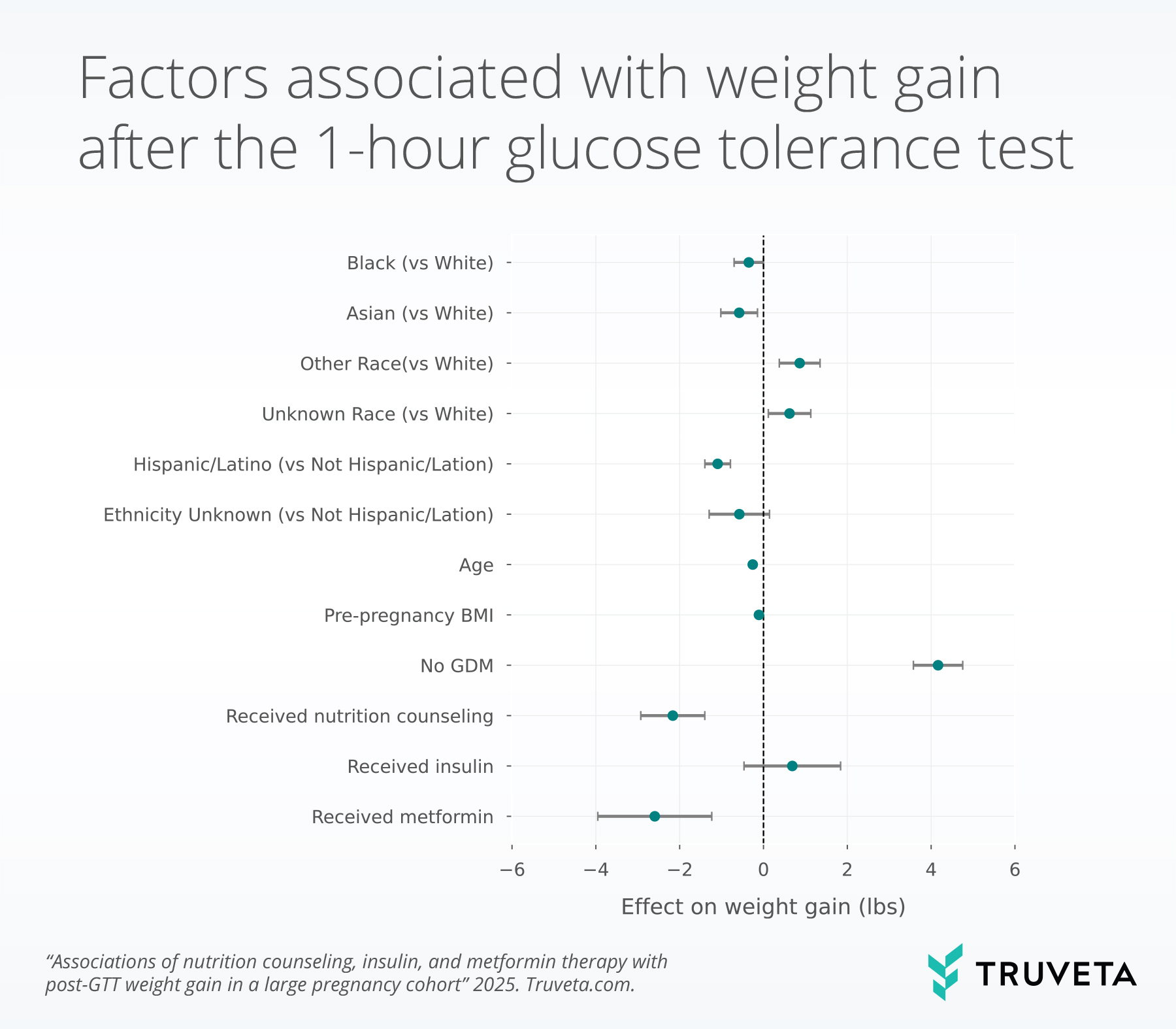

- Nutrition counseling and metformin use were each significantly associated with lower gestational weight gain following glucose testing (reductions of 2.2 and 2.6 pounds, respectively), when controlling for other factors, supporting their role in improving maternal outcomes during pregnancy.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is one of the most common complications of pregnancy, affecting an estimated 6–9% of pregnancies in the United States (1). GDM is associated with increased risk of hypertensive disorders, cesarean delivery, and macrosomia in the short term, as well as long-term risk of type 2 diabetes for both the mother and child (1–3). First-line management for GDM typically includes nutrition counseling designed to optimize glucose control during pregnancy (4). If lifestyle modifications are insufficient, pharmacologic therapy such as insulin or metformin may be initiated (5). While guidelines consistently recommend nutrition counseling as the cornerstone of GDM care, less is known about how consistently guidelines are followed in routine practice, how quickly they occur after diagnosis, and how they influence pregnancy weight gain.

Understanding these care patterns is important because timely nutrition counseling and appropriate pharmacotherapy can mitigate excess gestational weight gain, reduce the risk of macrosomia and cesarean delivery, and improve postpartum metabolic outcomes (6, 7).

Using a subset of Truveta Data, we built upon our prior analyses classifying GDM by lab values and weight gain in pregnancy to examine the receipt and timing of nutrition counseling, insulin, and metformin therapy among patients undergoing GDM testing. We further evaluated whether receipt of these interventions was associated with differences in weight gain following glucose testing, adjusting for demographic and clinical factors. You can explore the full analysis directly in Truveta Studio.

Methods

We used the same cohort as described in the previous analysis. In brief, using a subset of Truveta Data, we identified a cohort of women with evidence of a 1-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) between 2018 and August 2025, during their first pregnancy, and between the ages of 16–50 years. Women were required to have a gestational age diagnosis code (Z3A), continuous coverage of closed medical claims from 24–42 weeks gestation, and no prior type 1 or type 2 diabetes, claims for a glucose monitor, or nutrition counseling.

Glucose testing

We included three cohorts in this study:

- Passed 1-hour GTT cohort: This is the population who passed the 1-hour GTT.

- Passed 3-hour GTT cohort: This is the population who received the 3-hour GTT and passed with less than 2 elevated values.

- Gestational diabetes cohort: Patients were included in this cohort if they had one of the following: 2 elevated values on the 3-hour GTT or a gestational diabetes diagnosis. We describe the lab values in more detail in our previous report.

Nutrition counseling, insulin, and metformin therapy

Pregnancy weight gain

We used a logistic regression model to test the effect of weight gain after the 1-hour GTT test, controlling for race, ethnicity, age, pre-pregnancy BMI, receipt of nutrition counseling, insulin, and metformin.

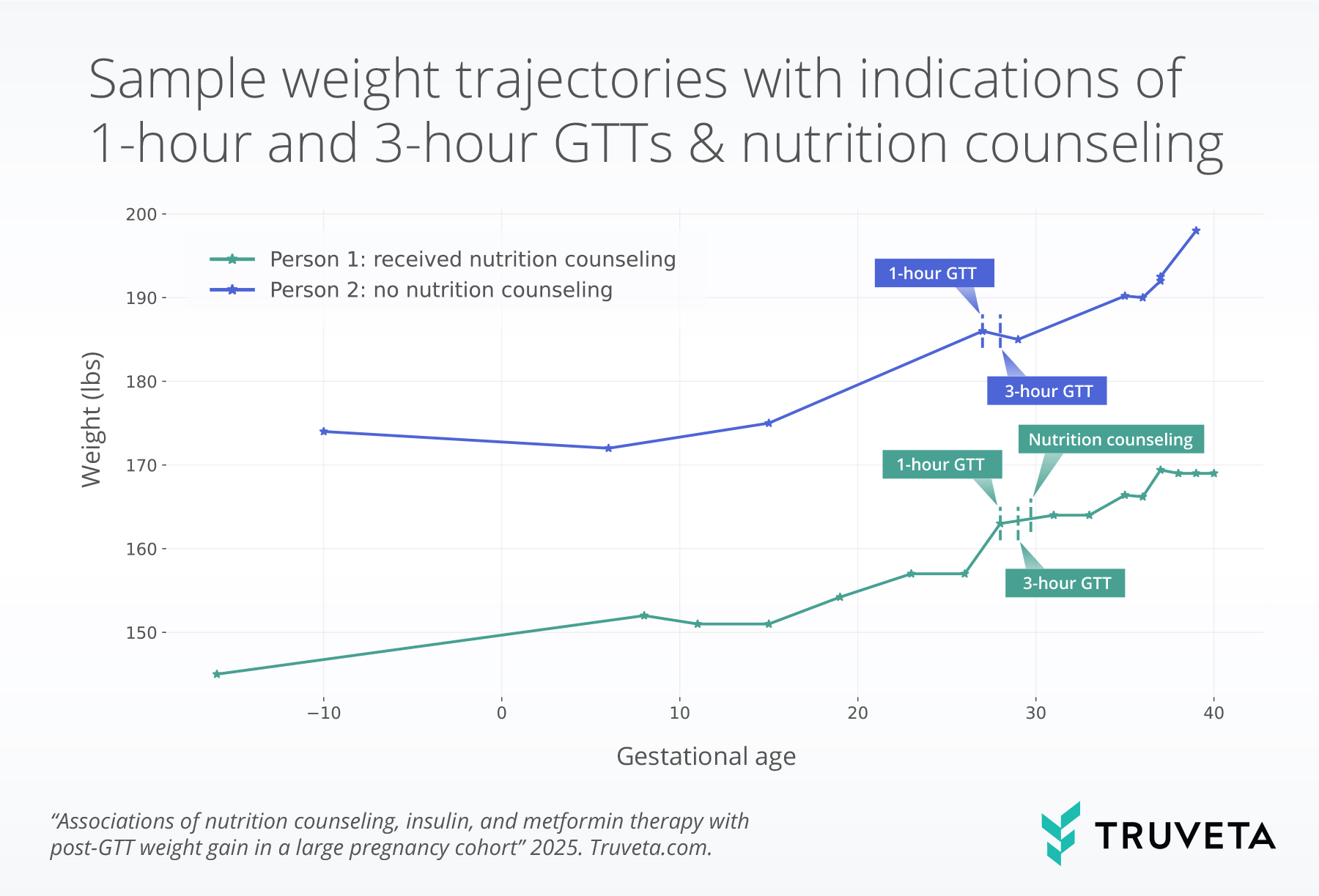

The sample figure below shows weight trajectories for two patients with GDM. The two patients had both the 1-hour and 3-hour glucose tests. Patient 1 received nutrition counseling, while patient 2 did not receive nutrition counseling.

Results

Evidence of nutrition counseling, insulin, or metformin

Time to treatment

Weight gain after GTT

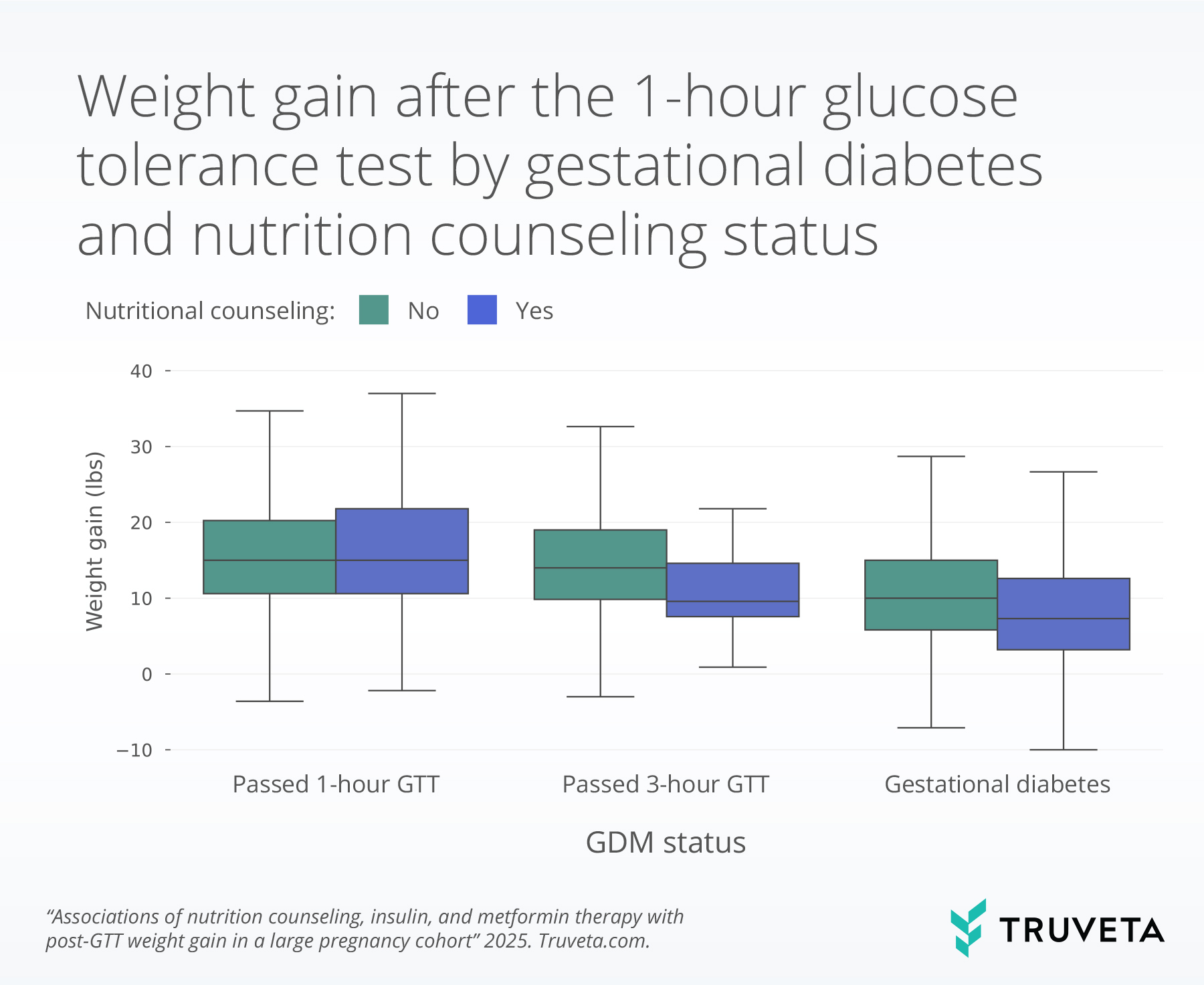

The boxplot below shows weight gain for a population who received nutrition counseling and for those who did not, by GDM cohorts. The line inside each box represents the median weight gain (or the 50th percentile). The bottom and top of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentile. Together the vertical space inside the box represents the middle half of all women. This is known as the interquartile range. The whiskers, or thin lines extending from the box, show typical lower and higher values, reaching up to 1.5 times the height of the box.

Predictors of weight gain after GTT

Metformin use within 45 days also showed a significant association with lower weight gain after the 1-hour GTT, with patients receiving metformin gaining a mean 2.6 fewer pounds than those who did not (p <0.001); however, the same trends were not seen in patients who received insulin.

Patients without gestational diabetes gained significantly more weight after the test than those who with gestational diabetes (coefficient 4.2, p<0.001).

Increased age, increased BMI, Asian or Black / African American race, and Hispanic ethnicity were also associated with less weight gain.

Discussion

Importantly, receipt of nutrition counseling was associated with lower weight gain after the GTT, with a mean reduction of 2.2 pounds compared to those without counseling. This finding is consistent with prior randomized trials and observational studies showing that nutrition therapy can reduce excess gestational weight gain and improve glycemic outcomes (4, 6, 12). Notably, a reduction of this magnitude represents a meaningful proportion of the weight typically recommended in the third trimester, which ranges from approximately 5 to 16 pounds depending on pre-pregnancy BMI (13). Moreover, even among women without GDM those who received nutrition counseling gained less weight, suggesting potential benefits beyond patients with confirmed GDM, although total gestational weight gain across the full pregnancy should also be considered.

Metformin use was less common than both nutrition counseling and insulin but showed a greater association with less weight gain. Both metformin and insulin are Class B drugs and typically reserved for women with more severe hyperglycemia. Still, our findings are consistent with prior studies reporting modest effects of metformin on gestational weight gain, even when compared to insulin (14–16). Beyond maternal weight, the literature has shown that metformin can improve glycemic control, reduce the need for insulin therapy, and in some cases, lower rates of pregnancy-induced hypertension and neonatal complications and may be easier to adhere to (14, 15, 17, 18). Although metformin may provide additional benefits for patients with GDM, it crosses the placental barrier (19) and therefore warrants additional research to balance the benefits and risks as part of comprehensive management strategies.

There are a few limitations associated with this study. First, to be included in the study, women were required to have continuous linked medical claims coverage. If a women changed coverage between 24 – 42 weeks gestation and either the first or second coverage was not part of the linked data, she would not be included in this study. Additionally, women who are uninsured are not captured in these data. We also required the 1-hour GTT to occur between 23 – 29 weeks gestation. We allowed a one-week buffer around the recommended window of 24 – 28 weeks (9); however, if a woman deviated from the standard recommended clinical care, she would not be included. If the 3-hour GTT happened outside a Truveta member health system, it would not be captured in this analysis; however, it is relatively unlikely that a patient would receive the follow up 3-hour GTT at a different facility than the 1-hour GTT. We used EHR data linked with closed medical claims to capture nutrition counseling, providing more complete coverage. However, if a patient was dually enrolled and those data were not available in the linked sources, evidence of counseling may still have been missed. Additionally, if patients talked with their primary provider and did not have a specialty visit for nutrition counseling, this may have been missed. We also assumed a prescription or dispense of a medication meant the patient was taking the medication, however we did not study adherence or differences by time to initiation. Finally, we used weight gain following the 1-hour GTT as a proxy measure. Future work should also examine other outcomes, including infant size, glucose measures, and subsequent development of gestational diabetes in both mother and child.

Despite these limitations, this study has several notable strengths, including its large, diverse population and linkage of EHR and claims data to capture both laboratory values and nutrition counseling encounters. By examining real-world care across more than 61,000 pregnancies, our analysis provides robust evidence on the timing and uptake of nutrition counseling and metformin therapy following glucose tolerance testing. Importantly, we demonstrate that nutrition counseling is associated with meaningful reductions in gestational weight gain, even among women who did not meet diagnostic thresholds for GDM. These findings highlight the central role of nutrition counseling in GDM management and suggest that timely intervention is linked to more favorable weight trajectories during pregnancy. Expanding access to dietary counseling offers an opportunity to limit excess gestational weight gain and improve outcomes for both mothers and infants.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on September 30, 2025.

Citations

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Gestational Diabetes (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/gestational-diabetes.html.

- The HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. N Engl J Med 358, 1991–2002 (2008).

- L. Bellamy, J.-P. Casas, A. D. Hingorani, D. Williams, Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 373, 1773–1779 (2009).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee, N. A. ElSayed, R. G. McCoy, G. Aleppo, K. Balapattabi, E. A. Beverly, K. Briggs Early, D. Bruemmer, J. B. Echouffo-Tcheugui, L. Ekhlaspour, R. Garg, K. Khunti, R. Lal, I. Lingvay, G. Matfin, N. Pandya, E. J. Pekas, S. J. Pilla, S. Polsky, A. R. Segal, J. J. Seley, R. C. Stanton, R. R. Bannuru, 15. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 48, S306–S320 (2025).

- K. C. Bishop, B. S. Harris, B. K. Boyd, E. S. Reiff, L. Brown, J. A. Kuller, Pharmacologic Treatment of Diabetes in Pregnancy. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 74, 289–297 (2019).

- S. Thangaratinam, E. Rogozinska, K. Jolly, S. Glinkowski, T. Roseboom, J. W. Tomlinson, R. Kunz, B. W. Mol, A. Coomarasamy, K. S. Khan, Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMJ 344, e2088–e2088 (2012).

- R. Wu, Q. Zhang, Z. Li, A meta-analysis of metformin and insulin on maternal outcome and neonatal outcome in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 37, 2295809 (2024).

- M. W. Carpenter, D. R. Coustan, Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 144, 768–773 (1982).

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstetrics & Gynecology 131, e49–e64 (2018).

- S. Guo, D. Liu, X. Bi, Y. Feng, K. Zhang, J. Jiang, Y. Wang, Barriers and facilitators to self-management among women with gestational diabetes: A systematic review using the COM-B model. Midwifery 138, 104141 (2024).

- U. Sovio, H. R. Murphy, G. C. S. Smith, Accelerated Fetal Growth Prior to Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study of Nulliparous Women. Diabetes Care 39, 982–987 (2016).

- K. Kapur, A. Kapur, M. Hod, Nutrition Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Ann Nutr Metab 76, 17–29 (2020).

- Institute of medicine, “Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines” (2009); https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/12584/Resource-Page—Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy.pdf.

- M. Balsells, A. Garcia-Patterson, I. Sola, M. Roque, I. Gich, R. Corcoy, Glibenclamide, metformin, and insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 350, h102–h102 (2015).

- S. Butalia, L. Gutierrez, A. Lodha, E. Aitken, A. Zakariasen, L. Donovan, Short‐ and long‐term outcomes of metformin compared with insulin alone in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabet. Med. 34, 27–36 (2017).

- K. He, Q. Guo, J. Ge, J. Li, C. Li, Z. Jing, The efficacy and safety of metformin alone or as an add‐on therapy to insulin in pregnancy with GDM or T2DM: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of 21 randomized controlled trials. Clinical Pharmacy Therapeu 47, 168–177 (2022).

- D. Farrar, M. Simmonds, M. Bryant, T. A. Sheldon, D. Tuffnell, S. Golder, D. A. Lawlor, Treatments for gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7, e015557 (2017).

- G. Priya, S. Kalra, Metformin in the management of diabetes during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs Context 7, 212523 (2018).

- T. N. Nanovskaya, I. A. Nekhayeva, S. L. Patrikeeva, G. D. V. Hankins, M. S. Ahmed, Transfer of metformin across the dually perfused human placental lobule. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 195, 1081–1085 (2006).