Extracting meaning from unstructured clinical text remains one of the hardest problems in healthcare. To solve this, many researchers rely on BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), a model first developed at Google in 2018. BERT reads language in both directions at once, allowing it to understand how words relate to one another in context. It set a new standard for natural language understanding and has become a foundation for many biomedical AI models.

In new findings presented at IJCAI 2025, researchers from Truveta and Iowa State University explored how large language models (LLMs) could help overcome this challenge. Their framework, called LLM-guided synthetic annotation, uses fine-tuned LLMs to generate structured biomedical labels—synthetic annotations that can then be used to train and enhance BERT-based models. (Download the full report here.)

The team found that combining human-labeled data with LLM-generated annotations improved BERT’s performance across biomedical named entity recognition (NER) tasks.

Introduction

Named entity recognition (NER) is a key task in biomedical natural language processing (NLP), helping identify important concepts such as diseases, drugs, and genes from unstructured text. While BERT-based models achieve strong performance in biomedical NER, they rely heavily on large amounts of high-quality annotated data—resources that are often limited and costly to obtain in the healthcare domain.

Large Language Models (LLMs), by contrast, excel at understanding context and generating coherent text, but tend to be less precise when it comes to fine-grained token-level predictions. This study investigates how LLMs can be leveraged as auxiliary annotators to enhance BERT’s performance, aiming to achieve a balance between efficiency and accuracy for real-world biomedical applications.

Methods

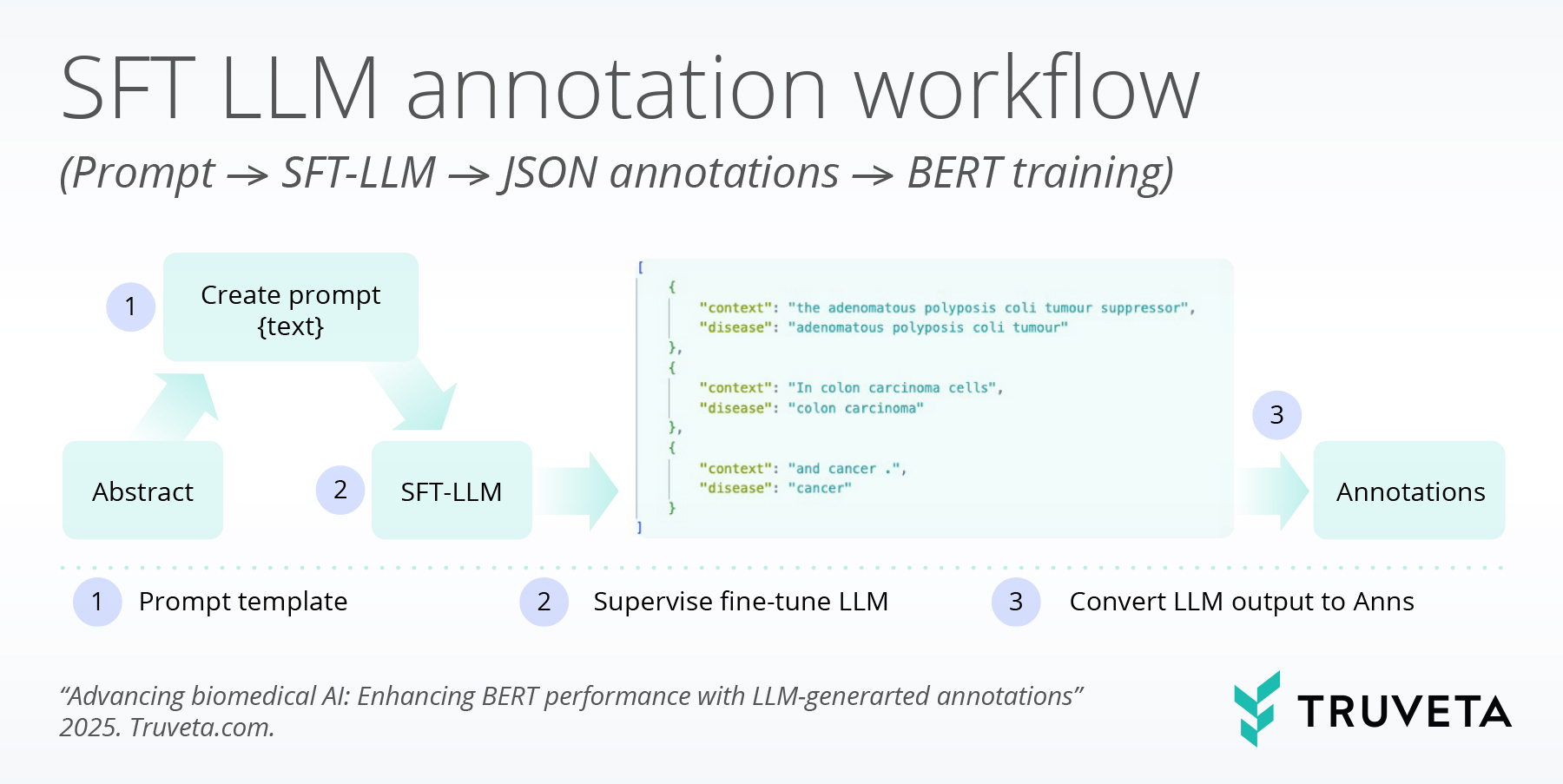

The team introduced LLM-guided synthetic annotation, a framework that leverages supervised fine-tuned (SFT) LLMs to produce structured biomedical annotations in JSON format. These structured outputs are then transformed into token-level labels for BERT-based NER models. The framework includes four key steps:

- Fine-tuning the LLM on existing biomedical annotations.

- Generating structured JSON outputs that capture entity spans, context, and labels.

- Decoding the JSON annotations into token-level NER labels.

- Integrating synthetic annotations with gold-standard labeled data to train span-based BERT NER models.

This method effectively turns the LLM into a large-scale auxiliary annotator. By blending high-quality human annotations with LLM-generated synthetic data, BERT can be trained more efficiently and robustly.

Results

Datasets

The researchers tested this approach on both public biomedical datasets and de-identified clinical notes from Truveta Data.

Experiments were conducted on the following datasets:

– NCBI Disease Corpus: 793 PubMed abstracts (593 train / 100 validation / 100 test).

– Truveta Dataset: 2,306 de-identified clinical notes (1,679 train / 313 validation / 314 test).

Auxiliary datasets:

– BC5CDR Corpus: 1,500 PubMed abstracts.

– BioRED Corpus: 5,935 PubMed abstracts.

– NCBI Validation Set: 100 abstracts.

– Unlabeled Clinical Notes from the proprietary corpus.

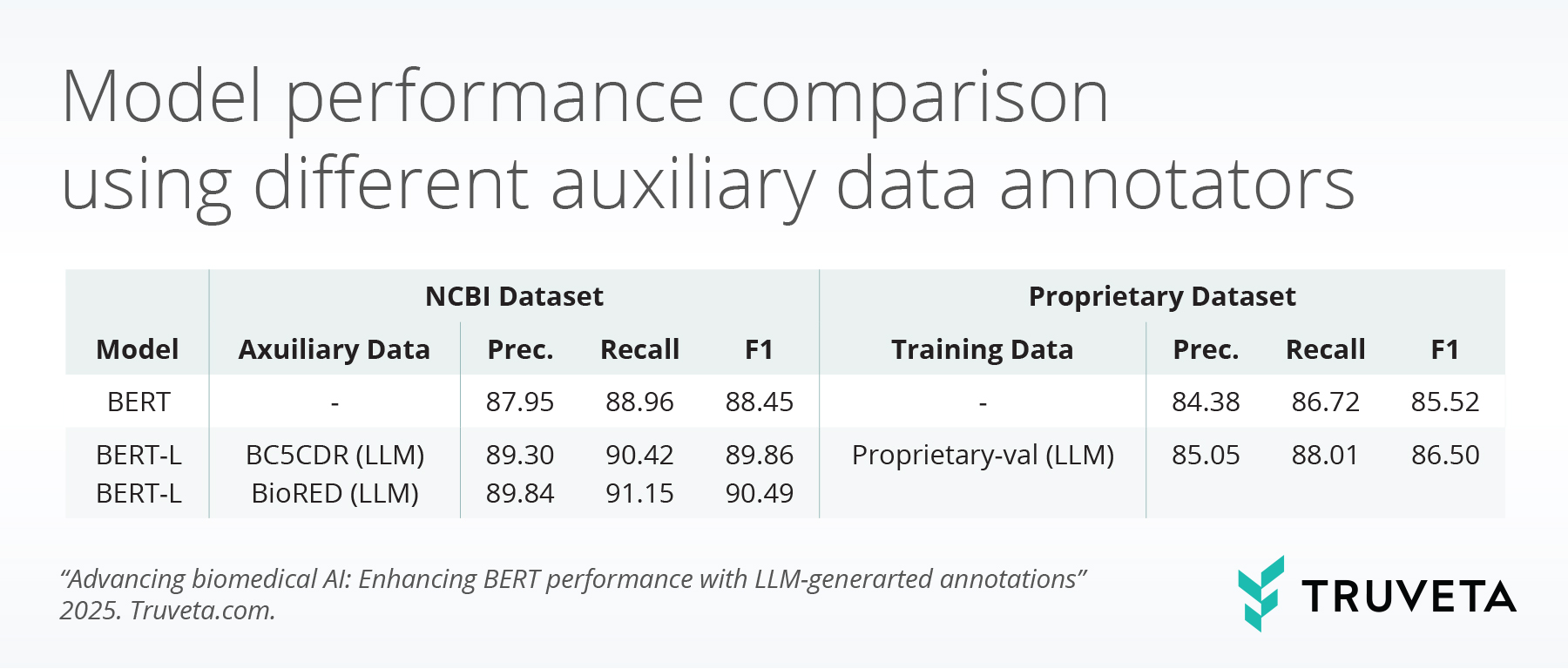

Model Performance

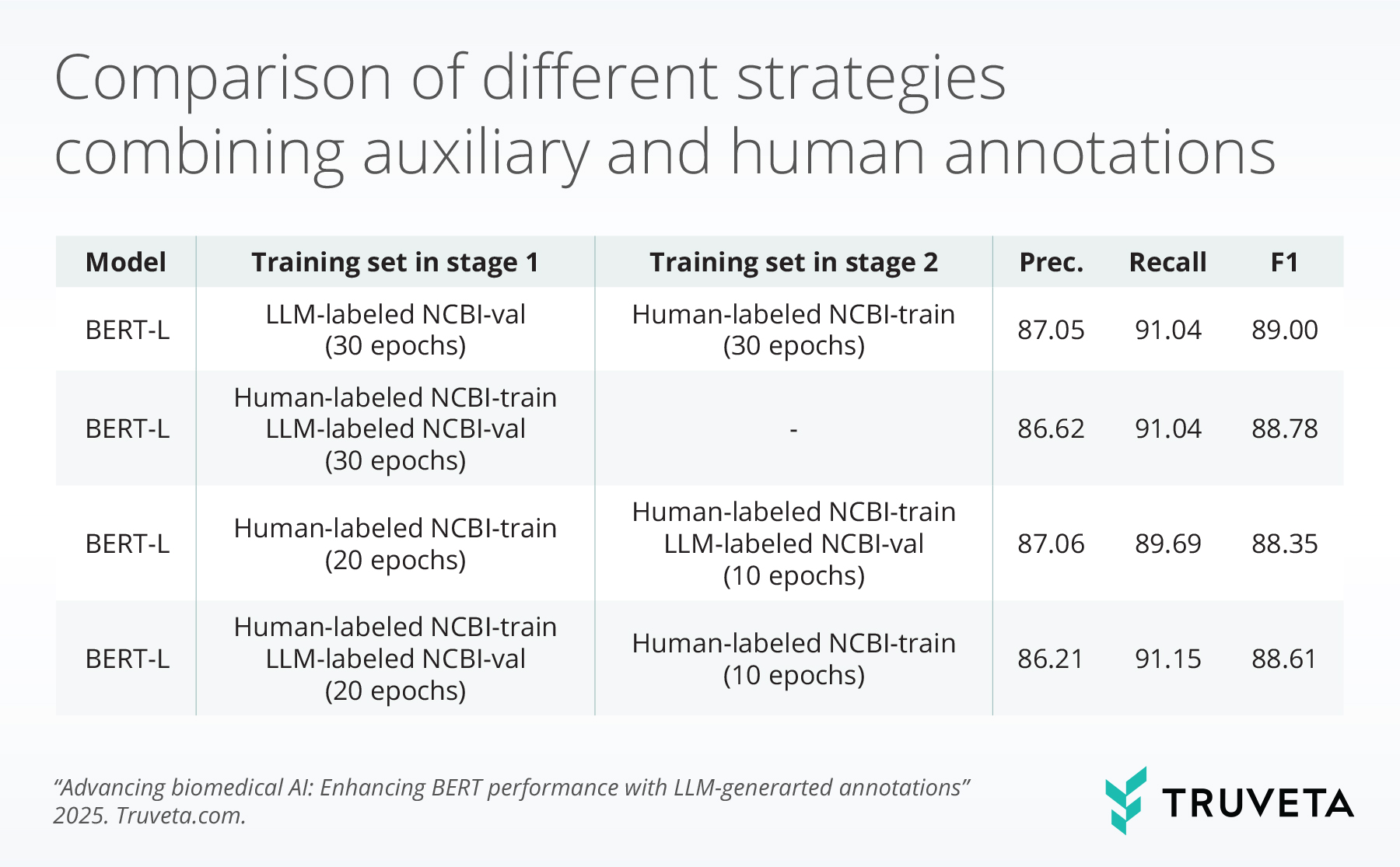

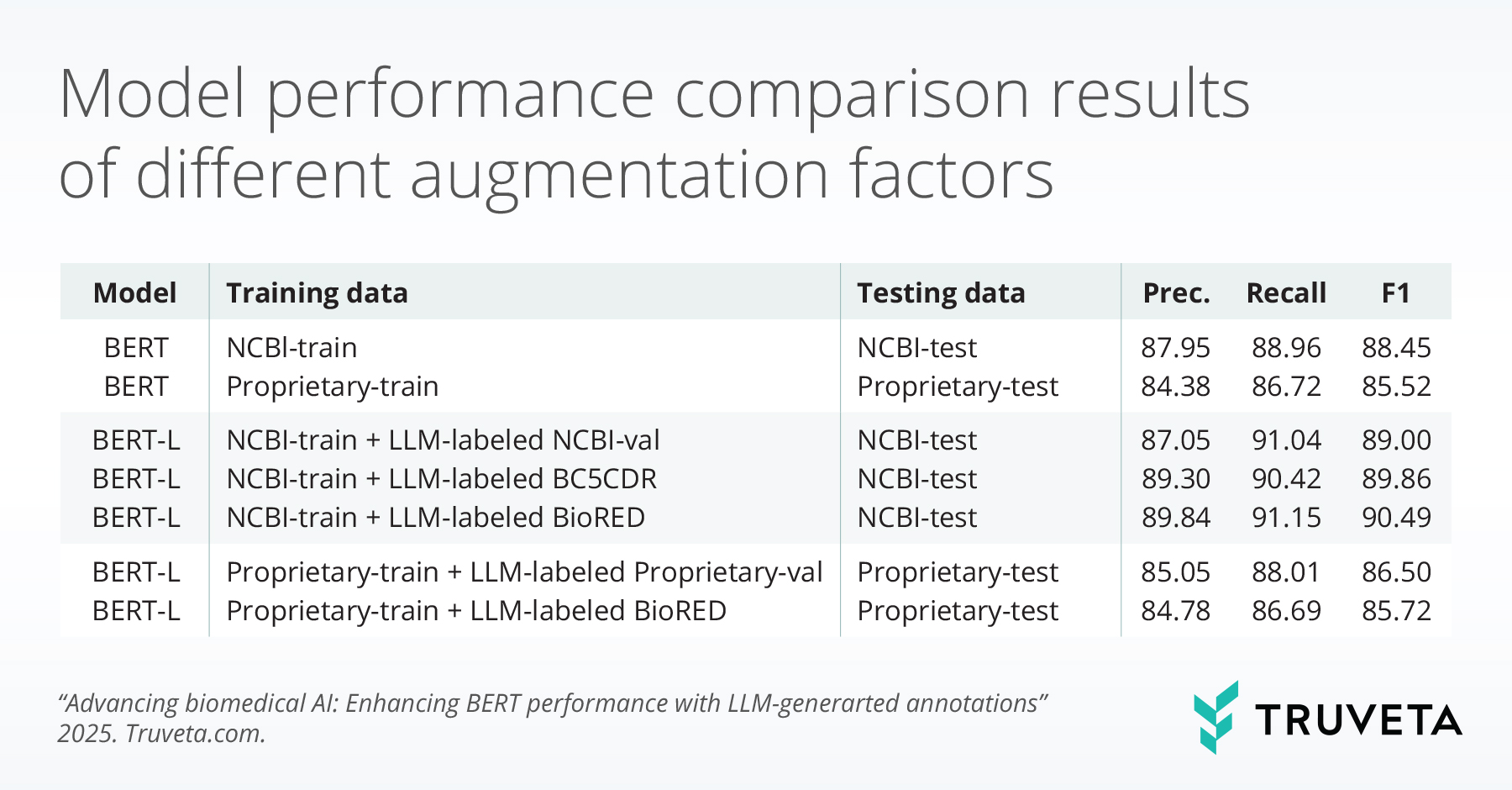

The tables below summarize BERT model performance enhancements from different perspectives when LLM-guided synthetic annotations are used.

Discussion

These findings show that LLMs, despite weaker direct NER performance, produce higher-quality auxiliary annotations than BERT models. This leads to consistent performance gains when augmenting BERT with LLM-generated data. Training strategies matter: early integration of auxiliary annotations, either jointly or in a warm-up phase, yields the strongest performance. Additionally, annotation scale has a positive effect, with large datasets such as BioRED delivering further improvements. Domain relevance is critical, as in-domain data yields higher performance, but large-scale out-of-domain annotations can mitigate domain mismatch.

This study demonstrates that LLM-generated auxiliary annotations effectively enhance BERT-based biomedical NER models. Combining small amounts of gold-labeled data with large-scale synthetic annotations yields substantial gains. LLM-based supervision is thus a scalable and practical alternative to manual annotation in low-resource biomedical domains.

Citations

[1] J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, K. Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–4186, 2019.

[2] Q. Lu, R. Li, A. Wen, J. Wang, L. Wang, H. Liu. Large language models struggle in token-level clinical named entity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.00731, 2024.

[3] C. Sun, Z. Yang, L. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Lin, J. Wang. Biomedical named entity recognition using BERT in the machine reading comprehension framework. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 118:103799, 2021.

[4] Z. Gouliev, R. R. Jaiswal. Efficiency of LLMs in identifying abusive language online: A comparative study of LSTM, BERT, and GPT. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Human Centred Artificial Intelligence–Education and Practice, 1–7, 2024.

[5] T. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. D. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:1877–1901, 2020.

[6] T. Schick, J. Dwivedi-Yu, R. Dessì, R. Raileanu, M. Lomeli, E. Hambro, L. Zettlemoyer, N. Cancedda, T. Scialom. Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36:68539–68551, 2023.

[7] Y. Zhang, D. G. Vlachos, D. Liu, H. Fang. Rapid adaptation of chemical named entity recognition using few-shot learning and LLM distillation. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 2025.

[8] X. Zhu, F. Dai, X. Gu, B. Li, M. Zhang, W. Wang. GL-NER: Generation-aware large language models for few-shot named entity recognition. In: International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Springer, 433–448, 2024.

[9] F. Villena, L. Miranda, C. Aracena. LLMNER: (Zero|Few)-shot named entity recognition, exploiting the power of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.04528, 2024.

[10] T. Hiltmann, M. Dröge, N. Dresselhaus, T. Grallert, M. Althage, P. Bayer, S. Eckenstaler, K. Mendi, J. M. Schmitz, P. Schneider, et al. NER4ALL or context is all you need: Using LLMs for low-effort, high-performance NER on historical texts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04351, 2025.

[11] S. Wang, X. Sun, X. Li, R. Ouyang, F. Wu, T. Zhang, J. Li, G. Wang. GPT-NER: Named entity recognition via large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.10428, 2023.

[12] M. Monajatipoor, J. Yang, J. Stremmel, M. Emami, F. Mohaghegh, M. Rouhsedaghat, K.-W. Chang. LLMs in biomedicine: A study on clinical named entity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07376, 2024.

[13] G. Tolegen, A. Toleu, R. Mussabayev. Enhancing low-resource NER via knowledge transfer from LLM. In: International Conference on Computational Collective Intelligence, Springer, 238–248, 2024.

[14] S. Sharma, A. Joshi, Y. Zhao, N. Mukhija, H. Bhathena, P. Singh, S. Santhanam. When and how to paraphrase for named entity recognition? In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 7052–7087, 2023.

[15] J. Ye, N. Xu, Y. Wang, J. Zhou, Q. Zhang, T. Gui, X. Huang. LLM-DA: Data augmentation via large language models for few-shot named entity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.14568, 2024.

[16] Y. Naraki, R. Yamaki, Y. Ikeda, T. Horie, K. Yoshida, R. Shimizu, H. Naganuma. Augmenting NER datasets with LLMs: Towards automated and refined annotation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.01334, 2024.

[17] W. Xu, R. Dang, S. Huang. LLM’s weakness in NER doesn’t stop it from enhancing a stronger SLM. In: Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Ancient Language Processing, 170–175, 2025.

[18] K. Hakala, S. Pyysalo. Biomedical named entity recognition with multilingual BERT. In: Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on BioNLP Open Shared Tasks, 56–61, 2019.

[19] U. Naseem, M. Khushi, V. Reddy, S. Rajendran, I. Razzak, J. Kim. BioALBERT: A simple and effective pre-trained language model for biomedical named entity recognition. In: International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), IEEE, 1–7, 2021.

[20] M. G. Sohrab, M. S. Bhuiyan. Span-based neural model for multilingual flat and nested named entity recognition. In: IEEE 10th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), 80–84, 2021.

[21] M. Zuo, Y. Zhang. A span-based joint model for extracting entities and relations of bacteria biotopes. Bioinformatics, 38:220–227, 2022.

[22] Y. Tang, J. Yu, S. Li, B. Ji, Y. Tan, Q. Wu. Span classification based model for clinical concept extraction. In: International Conference on Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery, Springer, 1880–1889, 2020.

[23] J. Santoso, P. Sutanto, B. Cahyadi, E. Setiawan. Pushing the limits of low-resource NER using LLM artificial data generation. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 9652–9667, 2024.

[24] M. S. Obeidat, M. S. A. Nahian, R. Kavuluru. Do LLMs surpass encoders for biomedical NER? arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.00664, 2025.

[25] S. Gao, O. Kotevska, A. Sorokine, J. B. Christian. A pre-training and self-training approach for biomedical named entity recognition. PLOS ONE, 16:e0246310, 2021.

[26] Z.-z. Li, D.-w. Feng, D.-s. Li, X.-c. Lu. Learning to select pseudo labels: A semi-supervised method for named entity recognition. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering, 21:903–916, 2020.

[27] Y. Wei, Q. Li, J. Pillai. Structured LLM augmentation for clinical information extraction. In: MEDINFO 2025—The Future Is Accessible, IOS Press, 2025.