Authors: Patricia J. Rodriguez, PhD, MPH ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA Duy Do, PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Brianna M. Goodwin Cartwright, MS ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Jennifer Liang, MD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Keenan Robbins, MBBS ⊕Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, Madhu Iyengar, MD ⊕Colorado Permanente Medical Group, Denver, CO,

Nicholas L. Stucky, MD, PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA

- CRC screening among adults aged 45–49 increased following May 2021 USPSTF recommendations to begin screening at age 45, instead of 50.

- After the recommendation change, pre-cancerous polyps were detected more often, while cancer was detected less often for ages 45-49.

This blog is an extension of our poster presented at ASCO 2025, titled Colorectal Cancer Screening and Detection Following USPSTF Recommendations for Ages 45-49: Insights from a Large EHR Cohort.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the US and a leading cause of cancer-related death (1). While most new CRC cases occur in adults aged 65-84 (1), CRC incidence and mortality in younger adults have been increasing over the past several decades (2–6). Individuals under age 50 now account for 12% of new CRC cases, with incidence increasing by approximately 2.2% per year (7).

Most CRC arises from polyps, which can progress to cancer over a period of many years (8–10). Routine CRC screening procedures, such as colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies, allow for polyp detection and removal, averting potential cases of CRC (11). Routine screening can also detect existing cancer at an earlier stage, leading to more favorable treatment prognoses.

In response to increasing CRC incidence in younger populations, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated its CRC screening recommendations in May 2021 to recommend that average-risk, asymptomatic adults begin CRC screening at age 45 instead of 50 (12). This followed similar guidance from the American Cancer Society in 2018 (13). Importantly, USPSTF recommendations impact insurance coverage, as insurers are currently required to cover USPSTF recommendations (grades A or B recommendations) without cost-sharing (e.g., no deductibles, copays, or coinsurance). As such, the USPSTF recommendation expanded both clinical guidance and effective access to CRC screening for average-risk adults aged 45-49.

A prior study found increased screening in this age group following the recommendation change (14). However, changes in detection of polyps and CRC following the USPTF recommendation have not been characterized. In this study, we used information extracted from clinical notes to compare CRC screening outcomes before and after the USPSTF recommendation change, stratified by 5-year age bands.

Methods

Using a subset of Truveta Data, we identified a population of patients aged 40-64 with no prior history of CRC who underwent a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy between 2018 and 2024 and had a pathology report from colonic specimens available. Truveta Data contains de-identified electronic health record (EHR) data from a collective of US health care systems.

Pathology findings were extracted from clinical notes using natural language processing. Only notes with “signed,” “final,” or “addendum” statuses were considered, and extraction was limited to the first pathology report per patient. Models extracted findings of polyps (tubular adenoma/adenomatous polyp, hyperplastic polyp, tubulovillous adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma, traditional sessile adenoma, juvenile polyp, and inflammatory polyp), cancer (adenocarcinoma), and benign/normal findings. Extracted findings were then mapped to SNOMED concepts. Family history of CRC and related syndromes (e.g., Lynch, Peutz-Jeghers) were similarly extracted from notes.

Screenings in May 2021 or earlier were classified as occurring before the USPSTF recommendation change. Patients were grouped by age (40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64) and timing relative to new USPSTF recommendations. Screening outcomes and patient characteristics within each age band were compared between time periods using chi-squared tests.

Results

Patient population

We identified 85,062 patients aged 40-64 who underwent screening with pathology reports available. Of these, 46,168 (54.3%) occurred before the USPSTF recommendation change, and 38,894 (45.7%) occurred after.

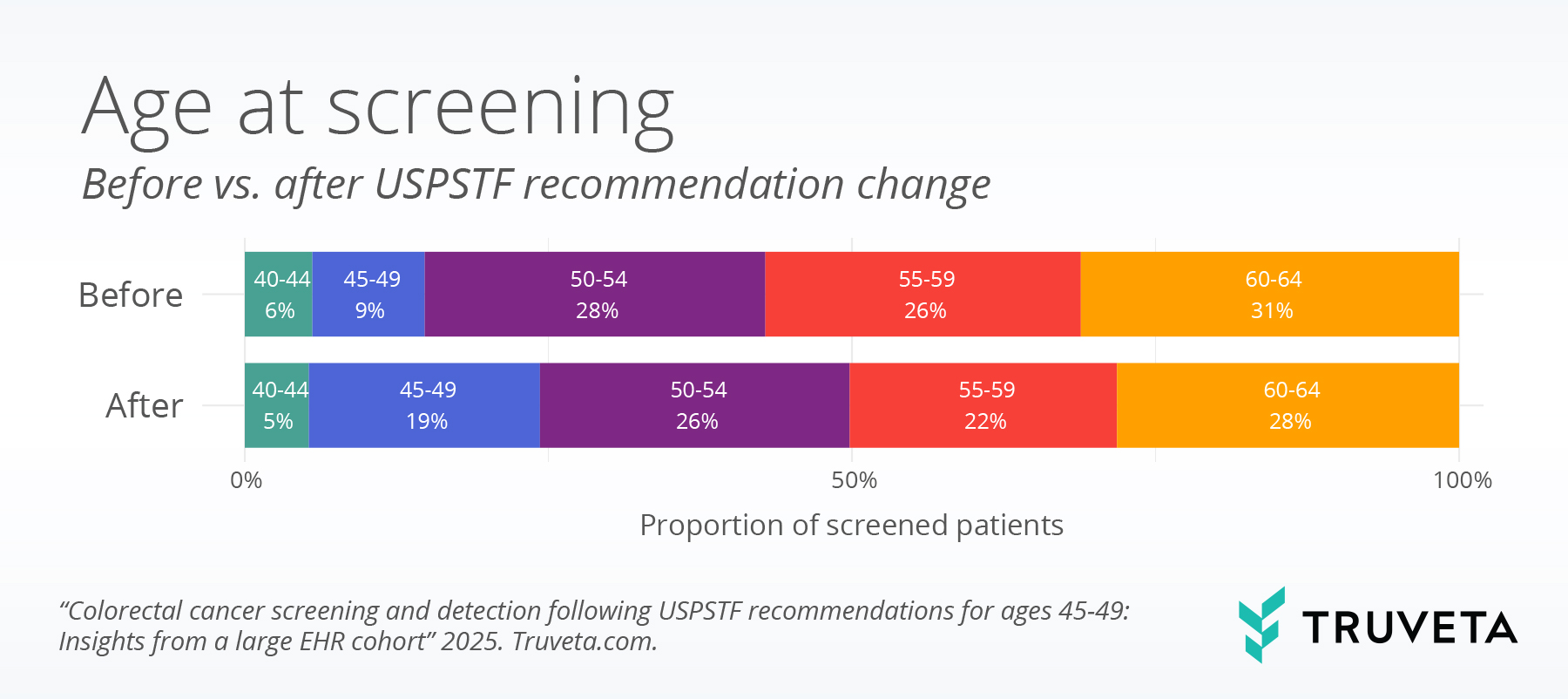

Figure 1: Age distribution at screening, before vs. after the USPSTF recommendation change.

Most patients included in the study were aged 50 or older (n = 68,769, 80.8%). However, adults aged 45-49 comprised a significantly larger proportion of the screened population following USPTF the recommendation change: 9% before vs 19% after (figure 1).

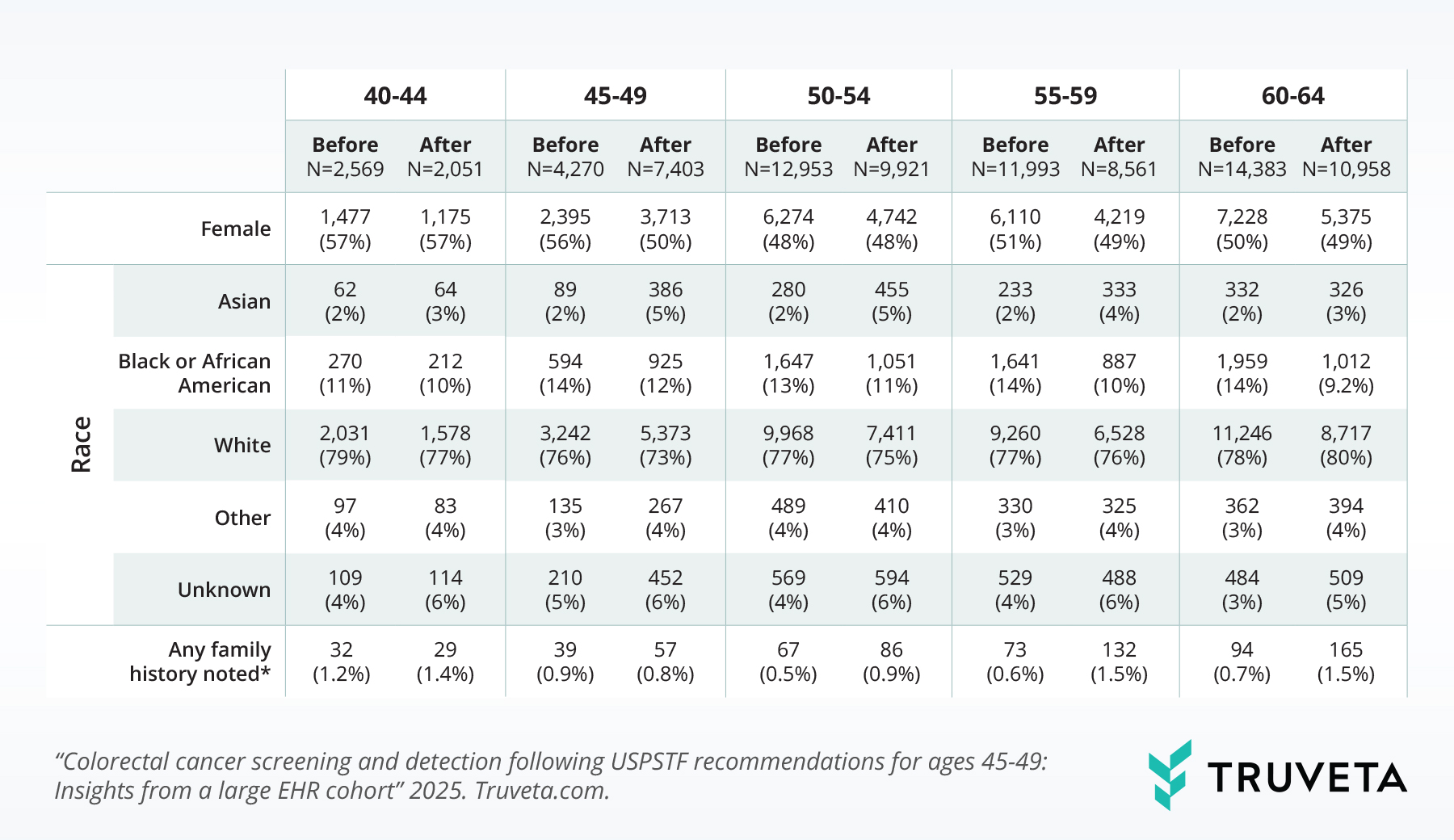

Table 1: Characteristics of patients at screening, by 5-year age band and time relative to USPTF guidelines. Note: Family history of CRC and related syndromes (e.g., Lynch, Peutz-leeghers) extracted from clinical notes.

Following the recommendation, the sex distribution in the 45–49 age group became more balanced (56% female before recommendations vs. 50% female after). Changes in sex balance were not observed in most other age groups (40-44: 57% female before vs. 57% female after, 50-54: 48% vs. 48%, 55-59: 51% vs.49%, 60-64: 50% vs. 49%; p < 0.05 for 55-59 only).

Screening outcomes

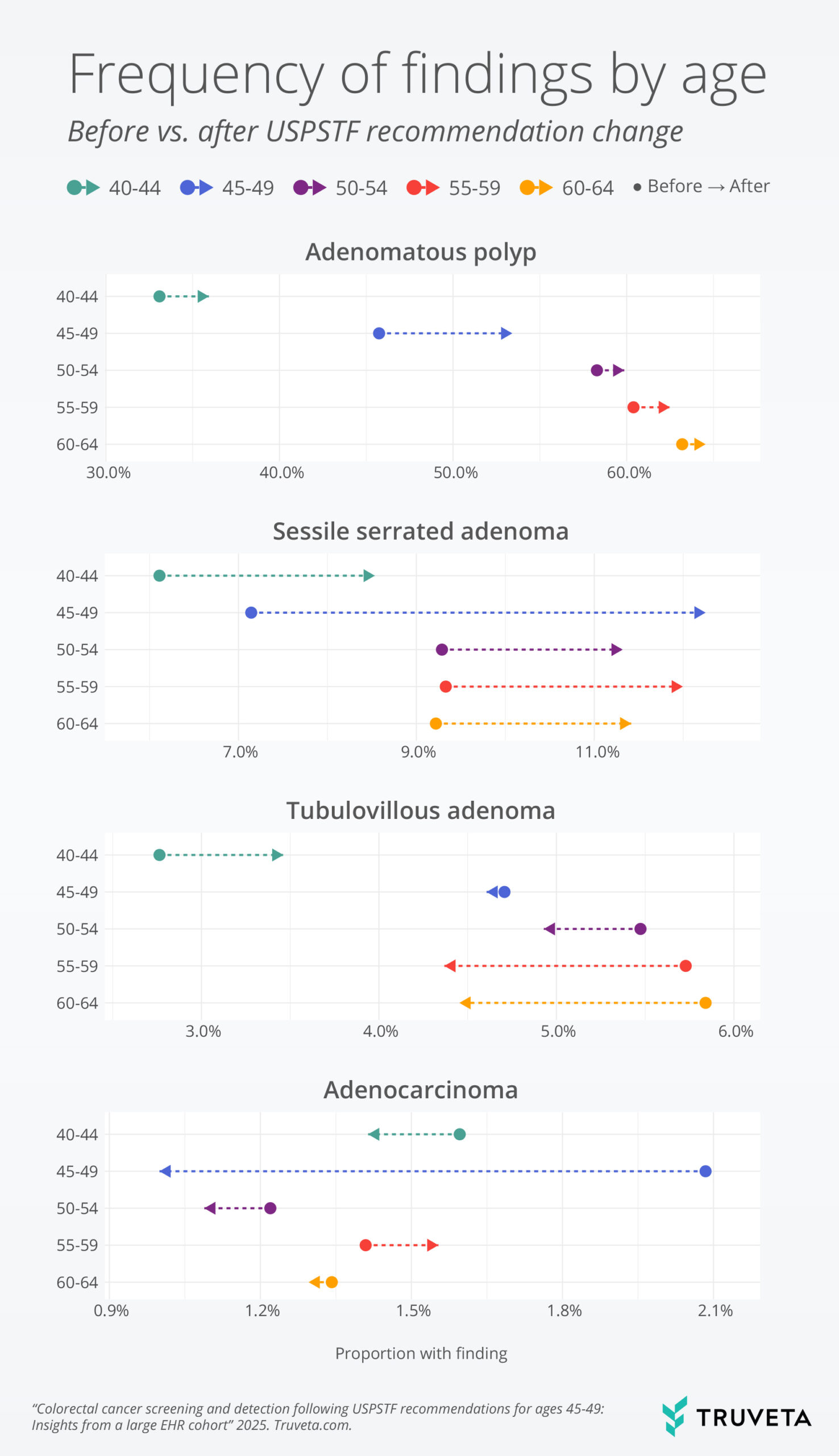

In both time periods, abnormal findings occurred more frequently for older patients. However, the largest changes in abnormal findings between periods were observed for patients aged 45-49. Adenomatous polyp findings increased significantly for patients aged 45-49, from 45.7% before to 53.4% after the recommendation change (p <0.01). In contrast, no significant differences in adenomatous polyps were observed for either younger or older age groups (40-44: 33.1% pre- vs. 35.9% post-, 50-54: 58.3% vs. 59.9%, 55-59: 60.4% vs. 62.5%, 60-64: 63.2% vs. 64.5%; all p <0.05). Sessile serrated adenomas increased significantly in all age groups, but to the largest degree for patients aged 45-49, from 7.1% to 12.3% (figure 2).

Conversely, adenocarcinoma (cancer) was detected less frequently for ages 45-49 after the new recommendations, occurring in 2.1% of screened patients before vs. 1.0% after (p < 0.01). In contrast, adenocarcinoma detection remained stable before vs. after recommendations in both younger patients and older age groups (40-44: 1.6% before vs. 1.4% after, 50-54: 1.2% vs. 1.1%, 55-59: 1.4% vs. 1.6%, 60-64: 1.3% vs. 1.3%; all p > 0.05) (figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of patients with findings noted, by age group and timing relative to USPTF recommendations. Adenomatous polyps and more specific adenoma categories are not mutually exclusive. Multiple findings can be noted within a screening, including both benign and abnormal findings.

Discussion

Following the USPSTF guideline change, CRC screening involving pathology increased substantially among 45–49-year-olds, and the gender balance of those screened improved. Within this age group, we observed higher detection of pre-cancerous polyps and lower detection of cancer. Similar changes were not observed for younger or older age groups.

Findings of increased screening align with a prior claims-based study finding significant increases in screening among those aged 45-49 following the recommendation change (14). This mirrors similar increases observed when Medicare adopted reimbursement for average-risk adults 50 and over in 2001 (15, 16).

Our study has several strengths. The use of extracted clinical notes allowed us to extend the work of previous studies that focused exclusively on screening uptake by assessing outcomes of the screenings. In addition, this study was not limited to patients with insurance. While USPSTF recommendations improve access and reduce the cost burden for insured patients, previous studies have documented disparities for uninsured patients (17).

This study also has several limitations. Only patients with pathology reports from colonic specimens were included, representing approximately 35% of all colonoscopies (18). As a result, these findings do not reflect patients with normal screenings in which no specimen collection or pathology occurred. Additionally, we focused on the first screening with a pathology report available, which may not represent the patient’s first-ever screening. Lastly, we did not adjust for potential delays in screening due to the COVID-19 pandemic (19, 20), which may have influenced detection rates.

CRC screening among adults aged 45–49 increased following USPSTF recommendations. In this group, detection of pre-cancerous polyps increased while cancer detection declined. These findings may reflect a positive impact of USPSTF recommendations, leading to earlier screening and removal of polyps before they become cancerous, or expected decreases in cancer detection with expansion to relatively lower-risk populations. Future studies are needed to explore complex causal relationships and long-term impacts of USPSTF recommendations.

Citations

- R. L. Siegel, T. B. Kratzer, A. N. Giaquinto, H. Sung, A. Jemal, Cancer statistics, 2025. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 75, 10–45 (2025).

- R. L. Siegel, S. A. Fedewa, W. F. Anderson, K. D. Miller, J. Ma, P. S. Rosenberg, A. Jemal, Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 109, djw322 (2017).

- E. M. Montminy, M. Zhou, L. Maniscalco, W. Abualkhair, M. K. Kim, R. L. Siegel, X.-C. Wu, S. H. Itzkowitz, J. J. Karlitz, Contributions of Adenocarcinoma and Carcinoid Tumors to Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates in the United States. Ann Intern Med 174, 157–166 (2021).

- G. Mauri, A. Sartore-Bianchi, A.-G. Russo, S. Marsoni, A. Bardelli, S. Siena, Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Molecular Oncology 13, 109–131 (2019).

- C. E. Bailey, C.-Y. Hu, Y. N. You, B. K. Bednarski, M. A. Rodriguez-Bigas, J. M. Skibber, S. B. Cantor, G. J. Chang, Increasing Disparities in the Age-Related Incidences of Colon and Rectal Cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surgery 150, 17–22 (2015).

- R. L. Siegel, K. D. Miller, A. Jemal, Colorectal Cancer Mortality Rates in Adults Aged 20 to 54 Years in the United States, 1970-2014. JAMA 318, 572–574 (2017).

- R. L. Siegel, K. D. Miller, A. Goding Sauer, S. A. Fedewa, L. F. Butterly, J. C. Anderson, A. Cercek, R. A. Smith, A. Jemal, Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 70, 145–164 (2020).

- B. Morson, The Polyp-Cancer Sequence in the Large Bowel. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 67, 451–457 (1974).

- S. J. Stryker, B. G. Wolff, C. E. Culp, S. D. Libbe, D. M. Ilstrup, R. L. MacCarty, Natural history of untreated colonic polyps. Gastroenterology 93, 1009–1013 (1987).

- S. J. Winawer, Natural history of colorectal cancer. The American Journal of Medicine 106, 3–6 (1999).

- M. Bretthauer, M. Løberg, P. Wieszczy, M. Kalager, L. Emilsson, K. Garborg, M. Rupinski, E. Dekker, M. Spaander, M. Bugajski, Ø. Holme, A. G. Zauber, N. D. Pilonis, A. Mroz, E. J. Kuipers, J. Shi, M. A. Hernán, H.-O. Adami, J. Regula, G. Hoff, M. F. Kaminski, Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death. New England Journal of Medicine 387, 1547–1556 (2022).

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 325, 1965–1977 (2021).

- A. M. D. Wolf, E. T. H. Fontham, T. R. Church, C. R. Flowers, C. E. Guerra, S. J. LaMonte, R. Etzioni, M. T. McKenna, K. C. Oeffinger, Y. T. Shih, L. C. Walter, K. S. Andrews, O. W. Brawley, D. Brooks, S. A. Fedewa, D. Manassaram‐Baptiste, R. L. Siegel, R. C. Wender, R. A. Smith, Colorectal cancer screening for average‐risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 68, 250–281 (2018).

- S. Siddique, R. Wang, F. Yasin, J. J. Gaddy, L. Zhang, C. P. Gross, X. Ma, USPSTF Colorectal Cancer Screening Recommendation and Uptake for Individuals Aged 45 to 49 Years. JAMA Network Open 7, e2436358 (2024).

- D. N. Prajapati, K. Saeian, D. G. Binion, D. M. Staff, J. P. Kim, B. T. Massey, W. J. Hogan, Volume and yield of screening colonoscopy at a tertiary medical center after change in medicare reimbursement. Am J Gastroenterology 98, 194–199 (2003).

- G. Harewood, Colonoscopy practice patterns since introduction of medicare coverage for average-risk screening. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2, 72–77 (2004).

- G. A. Benavidez, A. Zgodic, W. E. Zahnd, J. M. Eberth, Disparities in Meeting USPSTF Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines Among Women in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis 18, E37 (2021).

- D. A. Corley, C. D. Jensen, A. R. Marks, W. K. Zhao, J. K. Lee, C. A. Doubeni, A. G. Zauber, J. de Boer, B. H. Fireman, J. E. Schottinger, V. P. Quinn, N. R. Ghai, T. R. Levin, C. P. Quesenberry, Adenoma Detection Rate and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Death. New England Journal of Medicine 370, 1298–1306 (2014).

- G. S. Cooper, A. Chak, S. Koroukian, The polyp detection rate of colonoscopy: A national study of Medicare beneficiaries. The American Journal of Medicine 118, 1413.e11-1413.e14 (2005).

- A. K. Gupta, J. Samadder, E. Elliott, S. Sethi, P. Schoenfeld, Prevalence of any size adenomas and advanced adenomas in 40- to 49-year-old individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy because of a family history of colorectal carcinoma in a first-degree relative. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 74, 110–118 (2011).

- M. Aloysius, H. Goyal, T. Nikumbh, N. Shah, G. Aswath, S. John, A. Bapaye, S. Guha, N. Thosani, Overall Polyp Detection Rate as a Surrogate Measure for Screening Efficacy Independent of Histopathology: Evidence from National Endoscopy Database. Life 14, 654 (2024).

- H. Valian, M. Hassan Emami, A. Heidari, E. Amjadi, A. Fahim, A. Lalezarian, S. Ali Ehsan Dehkordi, F. Maghool, Trend of the polyp and adenoma detection rate by sex and age in asymptomatic average-risk and high-risk individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy, 2012–2019. Preventive Medicine Reports 36, 102468 (2023).

- R. L. Barclay, J. J. Vicari, A. S. Doughty, J. F. Johanson, R. L. Greenlaw, Colonoscopic Withdrawal Times and Adenoma Detection during Screening Colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 355, 2533–2541 (2006).

- R. C. Chen, K. Haynes, S. Du, J. Barron, A. J. Katz, Association of Cancer Screening Deficit in the United States With the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Oncology 7, 878–884 (2021).

- S. A. Fedewa, J. Star, P. Bandi, A. Minihan, X. Han, K. R. Yabroff, A. Jemal, Changes in Cancer Screening in the US During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open 5, e2215490 (2022).