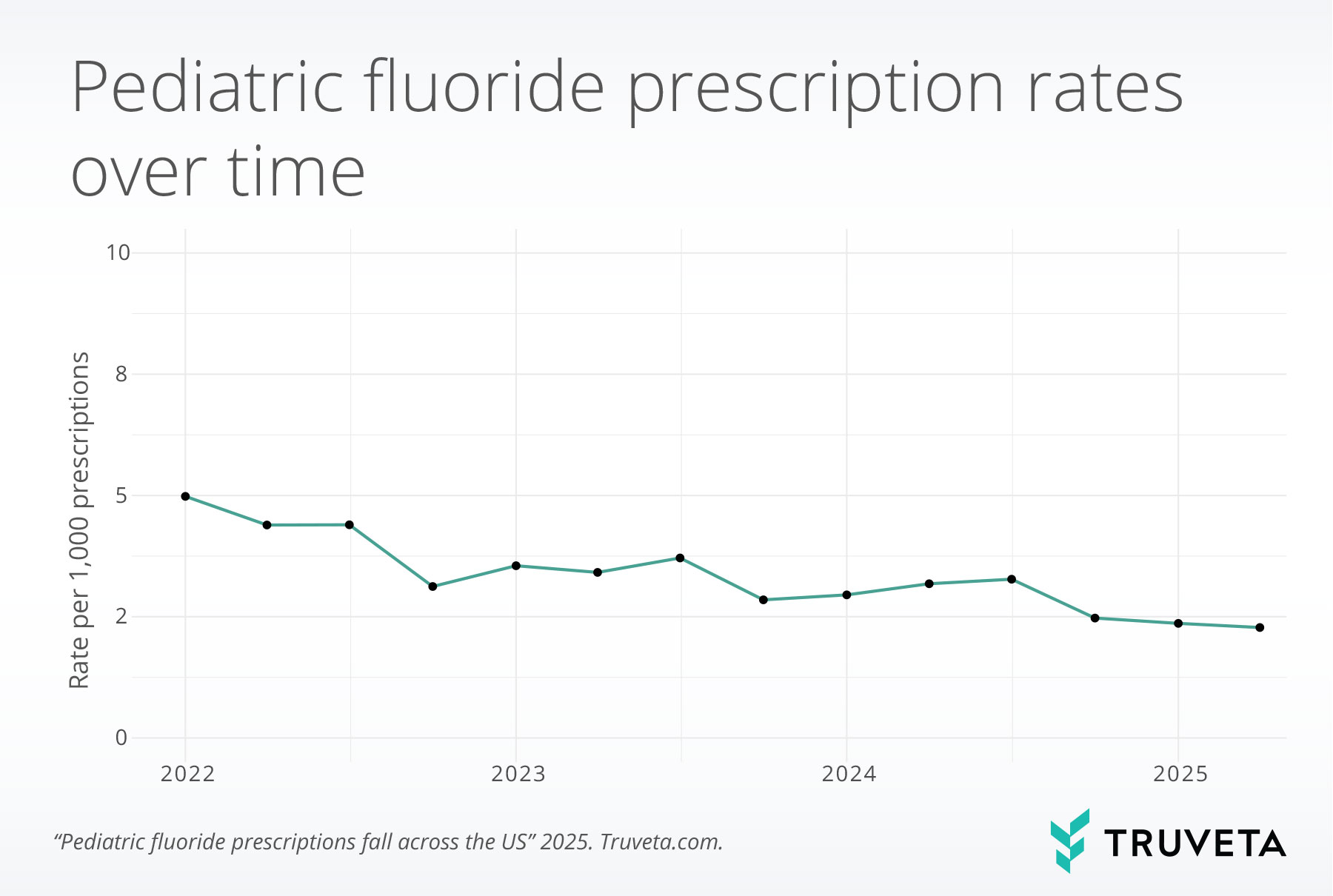

- The rate of pediatric fluoride prescriptions per all prescriptions decreased by 54.3% from the first quarter of 2022 (5.0 per 1,000 prescriptions) to the second quarter of 2025 (2.3 per 1,000 prescriptions).

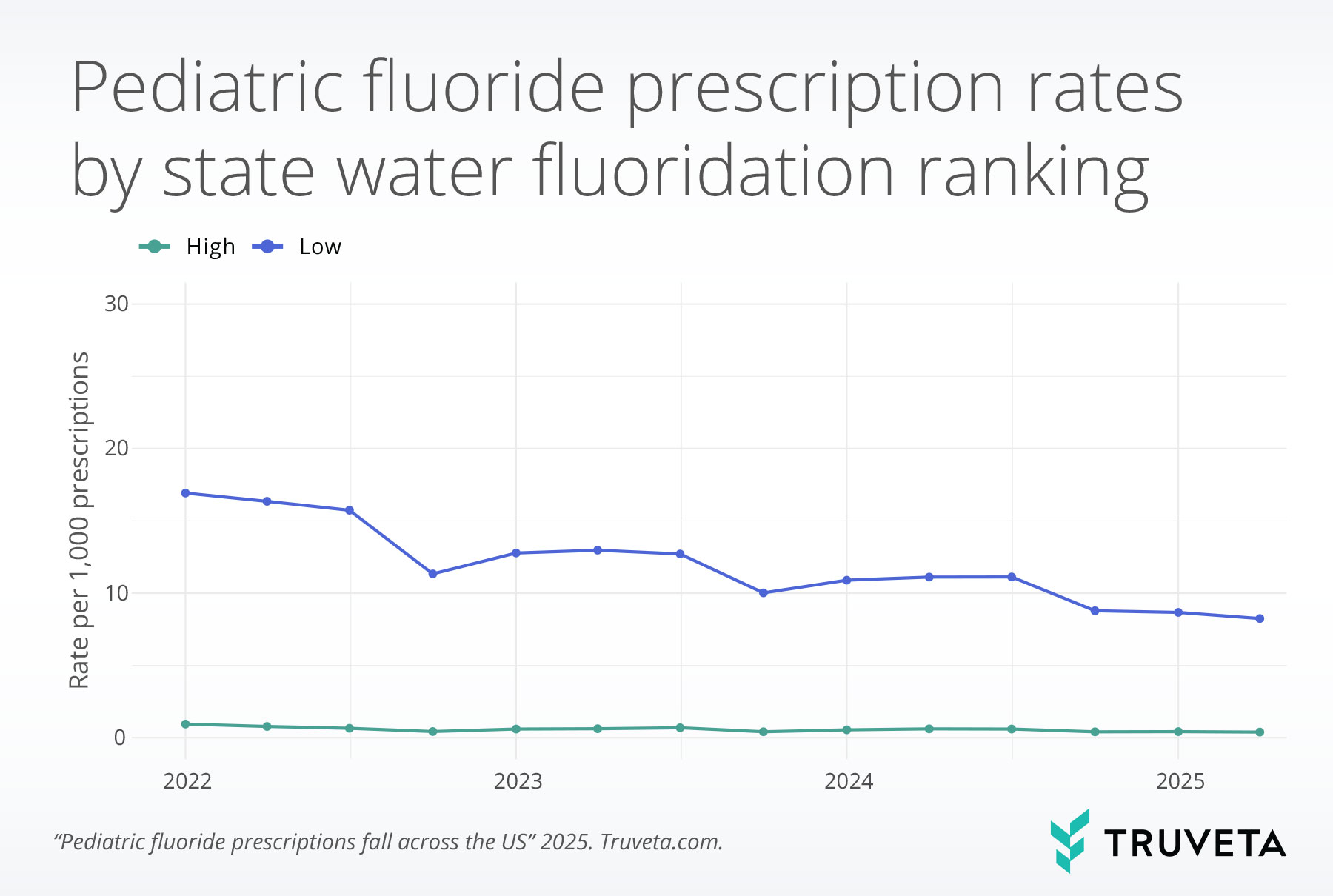

- Across the study period, the 10 US states with lowest community water fluoridation had a 20.8-fold higher rate of fluoride prescriptions compared to the 10 US states with high fluoridation. Although rates decreased for both sets of states across the study, absolute rates decreased more for states with low fluoridation (a decrease of 51.3% across the study period).

Decades of research demonstrate strong evidence that adding fluoride to community drinking water reduces the risk of tooth decay by strengthening enamel and reducing the risk of cavities (1–9). Community water fluoridation is a long-standing public health practice and is widely recognized by many leading professional organizations as the most effective method to deliver fluoride to large populations (1, 9–11). Water fluoridation was considered amongst the top 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century by the CDC (12).

An individual’s fluoride intake varies based on local fluoridation practices and household water sources; some communities do not fluoridate their water, and private wells may lack adequate fluoride (13). For children who do not receive enough fluoride through drinking water, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend fluoride supplements (14–18). These recommendations may be especially important for children at increased risk of tooth decay, such as those with limited access to dental care or those from lower-income households (18, 19).

Recently, there have been public discussions about the possibility of removing fluoride from public water supplies (20). Utah and Florida have enacted legislation limiting or prohibiting fluoride in public water, and at least 14 other states have proposed similar bills since the beginning of 2025 (21).

As communities consider reducing or eliminating fluoride in drinking water, one potential alternative for maintaining dental health is the use of fluoride supplements. While strong evidence supports the benefits of water fluoridation for dental health, research on the effectiveness of fluoride supplements is more nuanced and shows varied results (25–32). Although several studies have shown that fluoride supplements may reduce the risk of tooth decay, findings have been inconsistent, with outcomes varying based on factors such as patient age, type of supplement (e.g., ingestible tablet vs. topical gel), and differences in study design and evaluation methods (25–32). Methodological limitations—such as poor study quality, short follow-up periods, low adherence to supplements, and reliance on parent recall rather than clinical assessment—may also contribute to mixed results (33, 34). Additionally, some research suggests that exposure to fluoride levels above the recommended amounts may increase the risk of mild dental fluorosis, a cosmetic condition that can result in white spots or streaks on teeth but is unrelated to tooth function except in severe cases (35, 36).

In May 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced plans to review and potentially restrict fluoride prescription drug products for children (22). Taken together with proposed reductions in public water fluoridation, these actions could substantially decrease population-level fluoride exposure (23, 24).

Given potential changes to fluoridation in drinking water, it’s important to understand how fluoride supplement prescribing has shifted over time, especially across states with different fluoridation coverage and among different age groups. This report examines trends in pediatric fluoride prescription rates from 2022 through June 2025 to better inform public health strategies aimed at preventing tooth decay.

You can also view the entire study—including data definitions and code—directly within Truveta Studio.

Methods

We used a subset of Truveta Data to identify a population of pediatric patients between 6 months and 18 years who had a prescription between January 2022 and June 2025. For each month, we calculated the total number of prescriptions and the total number of fluoride prescriptions. We then computed the rate of monthly fluoride prescription relative to all prescriptions.

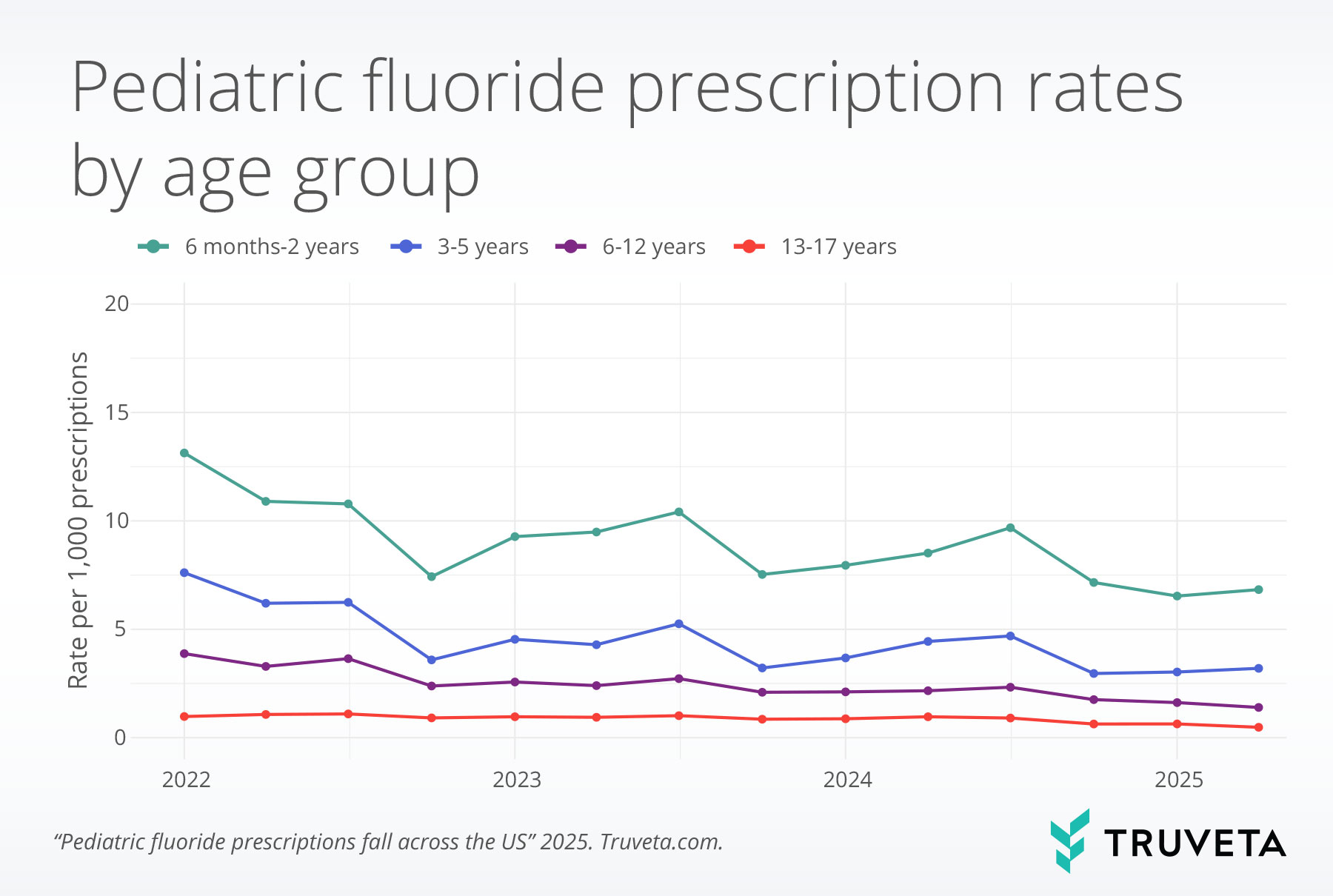

We examined overall trends in fluoride prescribing over time and also explored differences based on state fluoridation ranking, as well as patient age groups (6 months–2 years, 3–5 years, 6–12 years, 13–17 years).

To assess the relationship between community water fluoridation and fluoride prescribing patterns, we used the CDC’s 2022 National Water Fluoridation Statistics, which estimated fluoridation coverage among people served by public water systems (13). We identified the ten states with the highest (Kentucky, Minnesota, Illinois, North Dakota, Virginia, Georgia, South Dakota, Maryland, Ohio, South Carolina) and lowest (Hawaii, New Jersey, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Louisiana, Alaska, Utah, New Hampshire, Mississippi) fluoridation ranking and compared fluoride prescription rates across these two groups.

Results

Overall trends in fluoride prescriptions

We observed a shift in the proportion of fluoride prescriptions relative to total prescriptions over time. Fluoride prescriptions declined from 5.0 per 1,000 prescriptions in the first quarter of 2022 to 2.3 per 1,000 prescriptions in the second quarter of 2025, representing a 54.3% decrease.

Trends by state water fluoridation ranking

Across the study period, states with a low fluoridation ranking (i.e., lowest levels of community water fluoridation) had a 20.8-fold higher rate of fluoride prescriptions compared to states with a high fluoridation ranking (i.e., highest fluoridation levels).

Although prescription rates declined for both groups over time, absolute rates decreased more in the low-ranking states, with a 51.3% reduction observed across the study period.

In states with a high fluoridation ranking, fluoride prescriptions declined from 1.0 per 1,000 prescriptions in the first quarter of 2022 to 0.4 per 1,000 prescriptions in the second quarter of 2025.

In states with a low fluoridation ranking, fluoride prescriptions declined from 16.9 per 1,000 prescriptions in the first quarter of 2022 to 8.3 per 1,000 in the second quarter of 2025.

Trends by age

Between the first quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2025, fluoride prescription rates declined across pediatric age groups. Fluoride prescription rates were highest for the youngest age group and decreased with increasing age.

For children aged 6 months to 2 years, rates decreased from 13.1 to 6.8 per 1,000 prescriptions, a 48.0% decrease.

Among those aged 3 to 5 years, rates declined from 7.6 to 3.2 per 1,000 prescriptions, a 58.0% decrease.

Discussion

In this study, we found a substantial decline in the rate of pediatric fluoride prescriptions between 2022 and 2025. Fluoride prescriptions dropped by more than half during the study period, falling from 5.0 per 1,000 prescriptions in early 2022 to 2.3 per 1,000 prescriptions by mid-2025. This decline was observed nationwide, but patterns varied significantly by state fluoridation ranking.

In states with low public water fluoridation rankings, fluoridation prescription rates were over 20-fold higher than in states with high fluoridation rankings. This difference is consistent with public health recommendations to prescribe supplements in areas without access to fluoridated water. Prescription rates declined over time in both groups; from 16.9 to 8.3 per 1,000 prescriptions in low-fluoridation states, and from 1.0 to 0.4 per 1,000 prescriptions in high-fluoridation states. This sharp decline raises concern that children in areas with limited access to fluoridated water may increasingly lack sufficient fluoride exposure to prevent cavities, underscoring the need to monitor both clinical practices and community-level fluoride delivery strategies.

Declines were also observed across all pediatric age groups. Fluoride prescription rates were highest among younger children and lowest among adolescents. Our findings are consistent with earlier research showing that fluoride is more commonly prescribed for younger children (37). This likely reflects existing preventive care guidelines, which focus on early childhood, and the structure of pediatric care delivery. As children grow older and begin receiving regular dental care, physicians may prescribe fluoride less frequently.

Several factors may be contributing to the decline in pediatric fluoride prescriptions. Increased public discussion around the safety, toxicity, and effectiveness of fluoride may be influencing prescribing behavior and parental acceptance (38). A growing body of evidence suggests that this skepticism may be part of a broader trend, as a prior study found a significant association between opposition to fluoride and opposition to COVID-19 vaccination (39). Given the rise in vaccine hesitancy in recent years, it is plausible that fluoride hesitancy has increased in parallel (40, 41). Some of the current public discourse surrounding fluoride has also be influenced by recent research; a study published in January 2025 reported an association between lower childhood IQ and fluoride exposure at levels more than twice the concentration recommended for US community water systems (42).

In addition to evolving public attitudes, changes in clinical practice may also explain the decline in fluoride prescriptions. A study analyzing data from 2014 to 2018 observed an increase in the use of fluoride varnish—a professionally applied topical treatment—which may have continued in subsequent years (43). Physicians are more likely to recommend over-the-counter (OTC) fluoride toothpaste and fluoride varnish, rather than prescribe supplements (38). As a result, some providers may view fluoride supplements as unnecessary when fluoride is being delivered through these alternative methods.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis includes only prescriptions prescribed within a Truveta constituent healthcare system and thus does not capture fluoride treatments or supplements provided by dentists. Although a prior research study found that physicians are three times more likely to prescribe fluoride supplements than dentists (37), the absence of dental data may result in an underestimation of total fluoride prescriptions. This analysis also did not capture the use of toothpaste or other OTC products which contain fluoride. Additionally, we categorized states based on the 2022 CDC-reported fluoridation ranking, which reflects the proportion of residents receiving fluoridated public water systems. However, this metric may not fully capture individual-level access to fluoridated water, as in some states more than 25% of the population relies on non-public water sources (13). Finally, differences in the volume of prescribing activity may contribute to variation in rates.

Our findings highlight a meaningful shift in pediatric fluoride prescriptions in recent years. We observed a marked decline in prescribing, including in states with limited access to fluoridated water, where supplements are typically recommended as an alternative source of fluoride. These findings take on greater urgency in light of recent legislative efforts to limit or eliminate community water fluoridation, as well as the FDA’s announced plans to review the use of fluoride prescription drug products in children (22). If access to community water fluoridation declines, supplements may become a more important source of fluoride exposure, and these data provide a retrospective and current view into the prescribing landscape. This highlights a potential gap in preventive care that warrants close attention, particularly for children in communities without fluoridated water who may face greater risk for dental health problems.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on July 21, 2025.

Citations

- D. M. O Mullane, R. J. Baez, S. Jones, M. A. Lennon, P. E. Petersen, A. J. Rugg-Gunn, H. Whelton, G. M. Whitford, Fluoride and oral health. Community dental health 33, 69–99 (2016).

- D. Kanduti, P. Sterbenk, B. Artnik, FLUORIDE: A REVIEW OF USE AND EFFECTS ON HEALTH. Mater Sociomed 28, 133–137 (2016).

- K. Rošin-Grget, K. Peroš, I. Šutej, K. Bašić, The cariostatic mechanisms of fluoride. (2013).

- G. D. Slade, W. B. Grider, W. R. Maas, A. E. Sanders, Water Fluoridation and Dental Caries in U.S. Children and Adolescents. J Dent Res 97, 1122–1128 (2018).

- C.-Y. S. Hsu, K. J. Donly, D. R. Drake, J. S. Wefel, Effects of Aged Fluoride-containing Restorative Materials on Recurrent Root Caries. J Dent Res 77, 418–425 (1998).

- J. D. B. Featherstone, Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluoride. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 27, 31–40 (1999).

- Z. Iheozor-Ejiofor, T. Walsh, S. R. Lewis, P. Riley, D. Boyers, J. E. Clarkson, H. V. Worthington, A.-M. Glenny, L. O’Malley, Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Panel on Community Water Fluoridation, U.S. Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Rep 130, 318–331 (2015).

- H. P. Whelton, A. J. Spencer, L. G. Do, A. J. Rugg-Gunn, Fluoride Revolution and Dental Caries: Evolution of Policies for Global Use. J Dent Res 98, 837–846 (2019).

- L. W. Ripa, A Half-century of Community Water Fluoridation in the United States: Review and Commentary. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 53, 17–44 (1993).

- T. Zokaie, H. Pollick, Community water fluoridation and the integrity of equitable public health infrastructure. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 82, 358–361 (2022).

- Ten Great Public Health Achievements — United States, 1900-1999. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056796.htm.

- CDC, 2022 Water Fluoridation Statistics, Community Water Fluoridation (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/php/statistics/2022-water-fluoridation-statistics.html.

- M. B. Clark, M. A. Keels, R. L. Slayton, SECTION ON ORAL HEALTH, P. A. Braun, S. A. Fisher-Owens, Q. A. Huff, J. M. Karp, A. R. Tate, J. H. Unkel, D. Krol, Fluoride Use in Caries Prevention in the Primary Care Setting. Pediatrics 146, e2020034637 (2020).

- M. Jenco, AAP stands by recommendations for low fluoride levels to prevent caries (2024). https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/29918/AAP-stands-by-recommendations-for-low-fluoride.

- Task Force Recommends Fluoride for Oral Health in Children, AAFP (2021). https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20210601uspstfcaries.html.

- H. Silk, W. McCallum, Fluoride: The Family Physician’s Role. American Family Physician 92, 174–179 (2015).

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Screening and Interventions to Prevent Dental Caries in Children Younger Than 5 Years: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 326, 2172–2178 (2021).

- S. O. Griffin, C.-H. Li, Lorena Espinoza, B. F. Gooch, Filled dietary fluoride supplement prescriptions for Medicaid-enrolled children living in states with high and low water fluoridation coverage. J Am Dent Assoc 150, 854–862 (2019).

- EPA Press Office, EPA Will Expeditiously Review New Science on Fluoride in Drinking Water (2025). https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-will-expeditiously-review-new-science-fluoride-drinking-water.

- A. Jennemann, Get the Facts: What states have considered fluoride bans?, WBAL (2025). https://www.wbaltv.com/article/what-states-have-considered-fluoride-bans/64855417.

- R. G. Rozier, S. Adair, F. Graham, T. Iafolla, A. Kingman, W. Kohn, D. Krol, S. Levy, H. Pollick, G. Whitford, S. Strock, J. Frantsve-Hawley, K. Aravamudhan, D. M. Meyer, Evidence-Based Clinical Recommendations on the Prescription of Dietary Fluoride Supplements for Caries Prevention: A report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. The Journal of the American Dental Association 141, 1480–1489 (2010).

- D. G. Pendrys, O. Haugejorden, A. Baårdsen, N. J. Wang, F. Gustavsen, The risk of enamel fluorosis and caries among Norwegian children: implications for Norway and the United States. The Journal of the American Dental Association 141, 401–414 (2010).

- J. D. Bader, R. G. Rozier, K. N. Lohr, P. S. Frame, Physicians’ roles in preventing dental caries in preschool children: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. American journal of preventive medicine 26, 315–325 (2004).

- E. Oganessian, E. Lencova, Z. Broukal, Is systemic fluoride supplementation for dental caries prevention in children still justifiable. Prague Medical Report 108, 306–314 (2007).

- L. M. Lampert, D. Lo, Limited evidence for preventing childhood caries using fluoride supplements. Evid Based Dent 13, 112–113 (2012).

- S. Tubert-Jeannin, C. Auclair, E. Amsallem, P. Tramini, L. Gerbaud, C. Ruffieux, A. G. Schulte, M. J. Koch, M. Rège-Walther, A. Ismail, Fluoride supplements (tablets, drops, lozenges or chewing gums) for preventing dental caries in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2011).

- A. I. Ismail, H. Hasson, Fluoride supplements, dental caries and fluorosis: A systematic review. The Journal of the American Dental Association 139, 1457–1468 (2008).

- K. W. Davidson, M. J. Barry, C. M. Mangione, M. Cabana, A. B. Caughey, E. M. Davis, K. E. Donahue, C. A. Doubeni, M. Kubik, L. Li, Screening and interventions to prevent dental caries in children younger than 5 years: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama 326, 2172–2178 (2021).

- L. Tomasin, L. Pusinanti, N. Zerman, The role of fluoride tablets in the prophylaxis of dental caries. A literature review. Annali di stomatologia 6, 1 (2015).

- S. Flood, K. Asplund, B. Hoffman, A. Nye, K. E. Zuckerman, Fluoride Supplementation Adherence and Barriers in a Community Without Water Fluoridation. Academic Pediatrics 17, 316–322 (2017).

- A. I. Ismail, R. R. Bandekar, Fluoride supplements and fluorosis: a meta‐analysis. Comm Dent Oral Epid 27, 48–56 (1999).

- C. M. Vargas, Fluoride supplements prevent caries but can cause mild to moderate fluorosis. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice 11, 18–20 (2011).

- F. and D. Administration (FDA), FDA Begins Action to Remove Ingestible Fluoride Prescription Drug Products for Children from the Market (2025). https://www.hhs.gov/press-room/fda-to-remove-ingestible-fluoride-drug-products-for-children.html.

- Fluoride Amendments (2025; https://le.utah.gov/~2025/bills/static/HB0081.html).

- Governor Ron DeSantis Celebrates Action to Protect Floridians from Chemical and Technological Interference, Execuritve Office of the Governor Ron Desantis 46th Governor of Florida (2025). https://www.flgov.com/eog/news/press/2025/governor-ron-desantis-celebrates-action-protect-floridians-chemical-and.

- A. Ko, J. Banks, C. Hill, D. L. Chi, Fluoride Prescribing Behaviors for Medicaid-Enrolled Children in Oregon. Am J Prev Med 62, e69–e76 (2022).

- T. Bass, C. M. Hill, J. L. Cully, S. R. Li, D. L. Chi, A cross-sectional study of physicians on fluoride-related beliefs and practices, and experiences with fluoride-hesitant caregivers. PLOS ONE 19, e0307085 (2024).

- N. Weinstein, K. Schwarz, I. Chan, R. Kobau, R. Alexander, L. Kollar, L. Rodriguez, G. Mansergh, T. Repetski, P. Gandhi, L. Pechta, COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among US Adults: Safety and Effectiveness Perceptions and Messaging to Increase Vaccine Confidence and Intent to Vaccinate. Public Health Rep 139, 102–111 (2024).

- A. Kaushik, J. Fomicheva, N. Boonstra, E. Faber, S. Gupta, H. Kest, Pediatric Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States—The Growing Problem and Strategies for Management Including Motivational Interviewing. Vaccines 13, 115 (2025).

- G. J. Nowak, M. A. Cacciatore, State of Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States. Pediatric Clinics 70, 197–210 (2023).

- K. W. Taylor, S. E. Eftim, C. A. Sibrizzi, R. B. Blain, K. Magnuson, P. A. Hartman, A. A. Rooney, J. R. Bucher, Fluoride Exposure and Children’s IQ Scores: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 179, 282–292 (2025).

- T. Gracner, A. M. Kranz, K. Li, A. W. Dick, K. Geissler, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and Pediatric Medical Clinicians’ Application of Fluoride Varnish. JAMA Netw Open 6, e2343087 (2023).