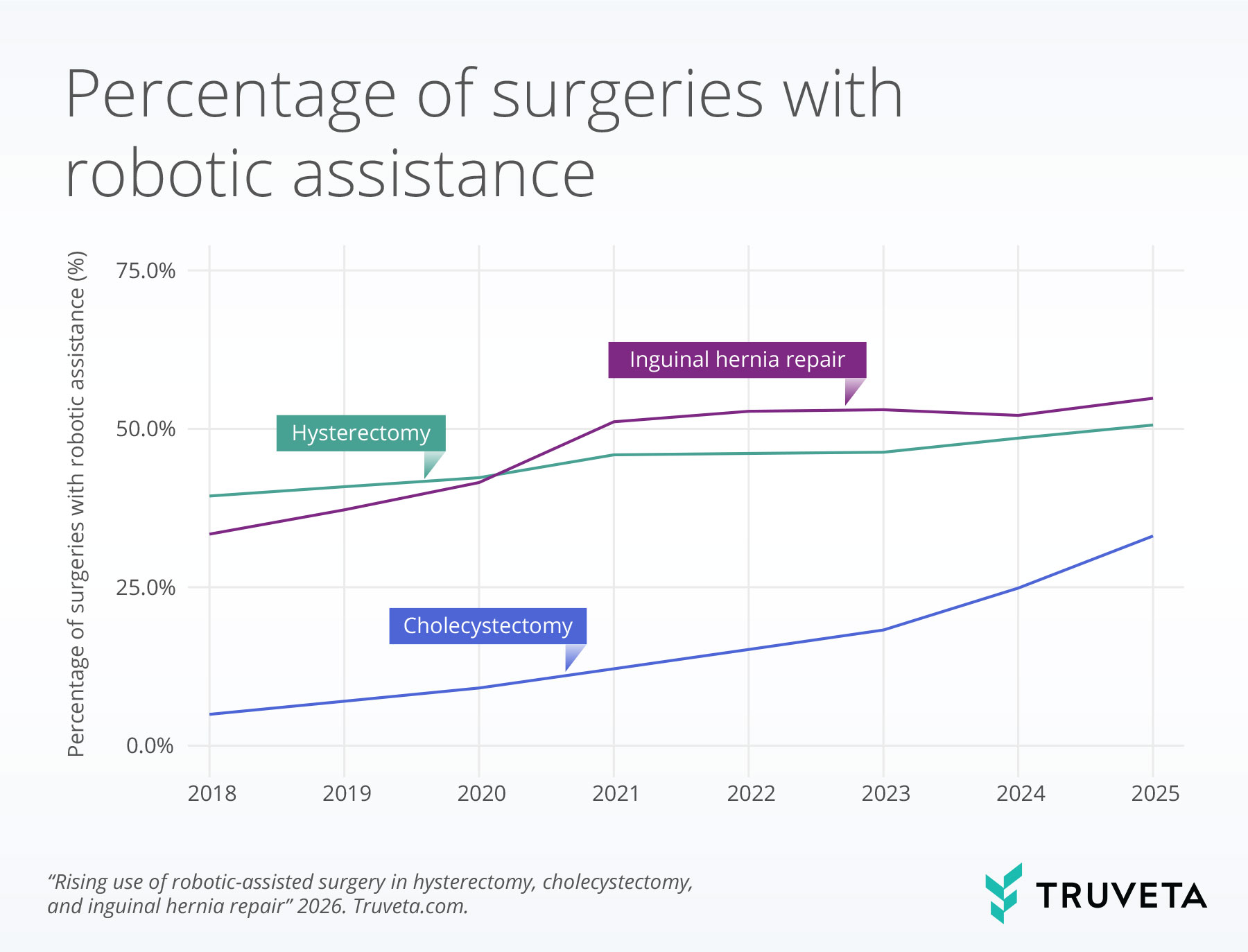

- From 2018 to 2025, robotic-assisted surgery increased across hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, with robotic use in cholecystectomy increasing more than six-fold over the study period.

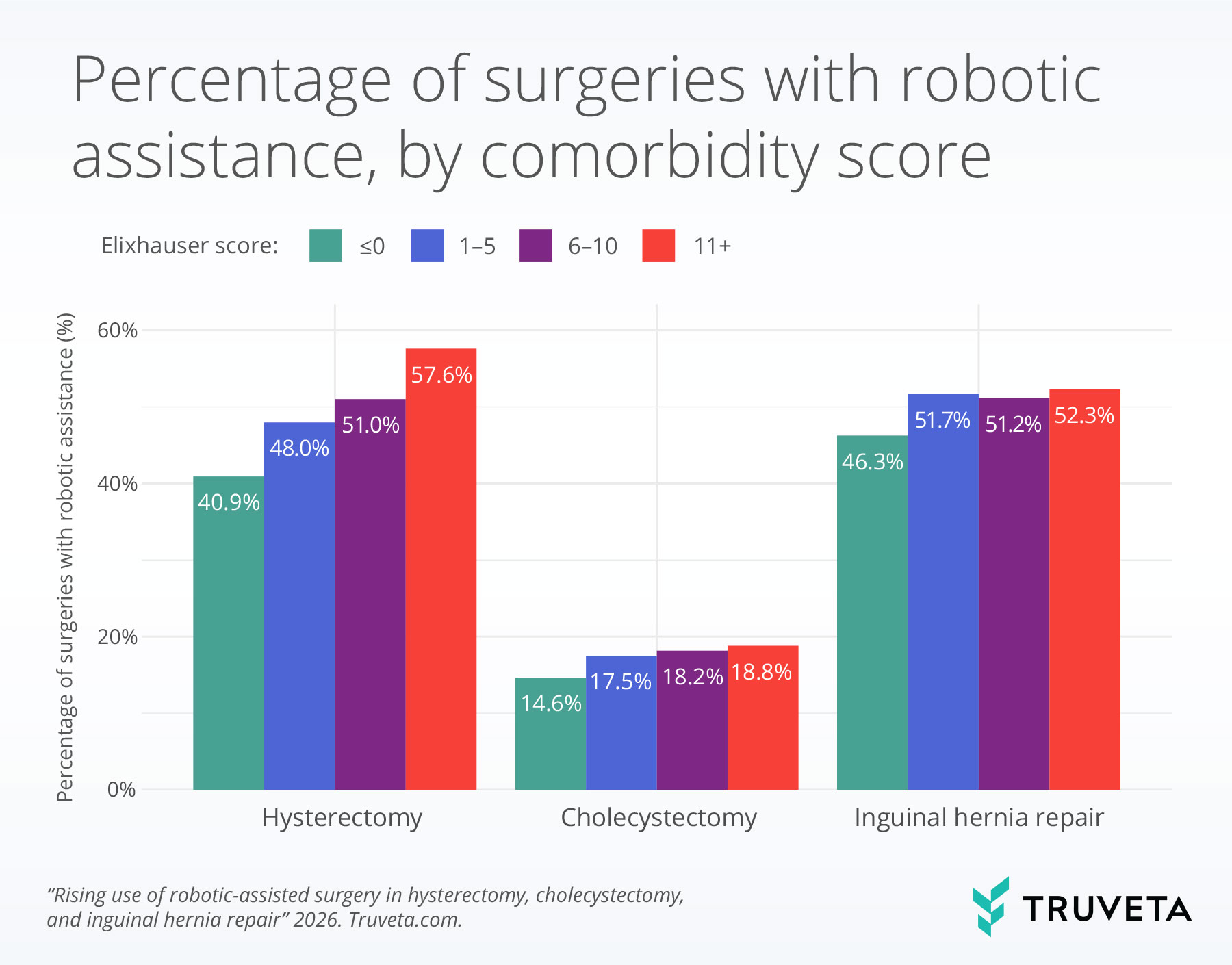

- Across all procedures, patients with higher comorbidity burden (measured by the Elixhauser comorbidity score) were more likely to undergo robotic-assisted surgery.

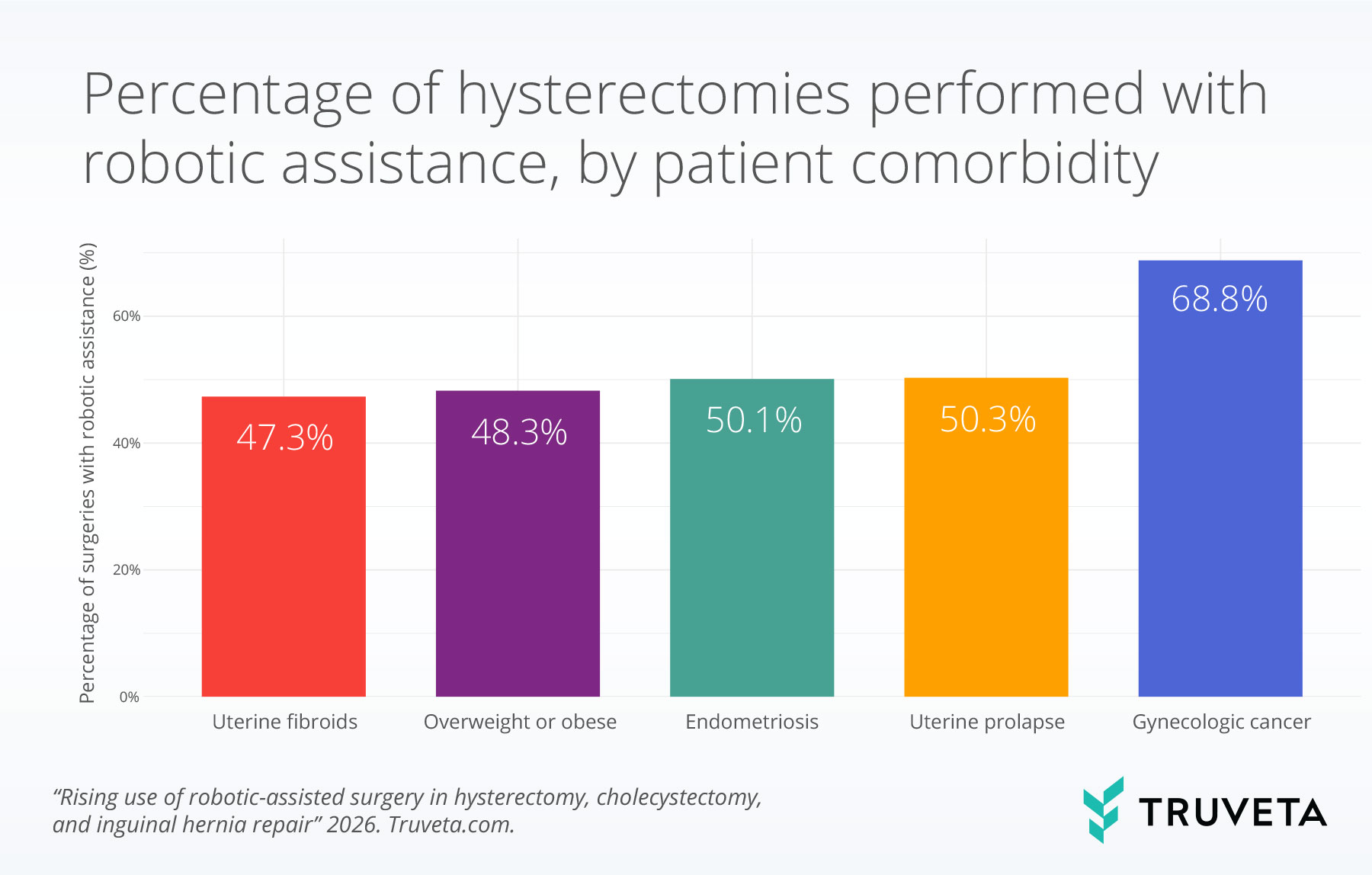

- For hysterectomy, robotic-assisted surgery was most used by gynecologic oncology physicians and among patients with gynecologic cancer.

Minimally invasive surgery has transformed surgical care over the past several decades, resulting in lower mortality, shorter hospital stays, reduced postoperative pain, and faster recovery compared to open procedures (1–3). Robotic-assisted surgery is an extension of minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that uses robotic arms to position and manipulate surgical instruments under the surgeon’s control (4). These systems provide high-definition, three-dimensional views of the surgical field, and more flexible instruments, which are designed to give surgeons greater precision than standard laparoscopy (4, 5). Studies comparing robotic-assisted surgery with standard laparoscopy generally show similar clinical outcomes, including comparable rates of major complications and readmissions (6–9). Some studies suggest lower blood loss with robotic-assisted surgery, but nearly all report longer operating times and higher costs (7, 10–12).

Since their introduction, robotic platforms have been adopted across multiple surgical specialties, with use expanding to a wide range of procedures over time (13–15). In parallel, the robotic surgery landscape has continued to evolve, with new robotic platforms entering the market and ongoing technological advancements (16–18). These developments may influence how and where robotic-assisted surgery is used as newer technologies are incorporated into clinical practice. While several studies have documented increases in robotic-assisted surgery use, there is limited published evidence describing how the use of robotic-assisted surgery has changed in recent years (2, 19, 20). Moreover, real-world adoption of robotic-assisted surgery is shaped not only by available technology but also by patient characteristics, including age, comorbidity burden, and clinical complexity, which may influence when and for whom robotic approaches are used (21, 22). This study includes three common surgical procedures: hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair. A hysterectomy is surgery to remove the uterus and is often performed to treat conditions such as heavy bleeding, fibroids, endometriosis, or cancer. A cholecystectomy is surgery to remove the gallbladder, most commonly to treat gallstones that cause pain or infection. An inguinal hernia repair is surgery to fix a weakness in the lower abdomen or groin where tissue can bulge through. Looking at these procedures, we examine recent trends in robotic-assisted surgery and evaluate how use varies by patient characteristics, clinical context, and provider-related factors.

Methods

We used a subset of Truveta Data to identify adults undergoing one of three common laparoscopic procedures: hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, or inguinal hernia repair from January 1, 2018 to October 31, 2025. A surgery was classified as robotic-assisted if either a robotic procedure code or documentation of a robotic device was present on the day of surgery.

For each patient, we captured demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and rural–urban residence), the surgeon’s sex and specialty, and the weighted Elixhauser comorbidity score on the day of surgery. The Elixhauser comorbidity score provides a single number that reflects how many chronic health conditions a patient has and how serious those conditions are (23). We calculated the score on the day of surgery by checking for a standardized list of medical conditions in the patient’s prior health records and applying established weights that indicate the relative impact of each condition on health risk. Higher scores reflect worse underlying health.

For each procedure, we also looked at comorbidities within the prior two years relevant to each surgery type:

- Hysterectomy: Gynecological cancers, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, uterine prolapse, overweight or obesity

- Cholecystectomy: Cholecystitis, gallstone disease, and overweight or obesity

- Inguinal hernia repair: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, benign prostatic hyperplasia, constipation, and overweight or obesity

We examined trends in robotic-assisted surgery. Using logistic regression, a statistical tool for understanding what factors are associated with the likelihood of an outcome occurring, we examined how variation in robotic-assisted surgery use was associated with patient demographics, surgeon characteristics, Elixhauser comorbidity scores, and procedure-specific clinical conditions. This approach allows us to assess the relationship between each factor while accounting for the others at the same time. We only highlight a subset of associations that were statistically significant.

You can view the entire study directly in Truveta Studio.

Results

This analysis included a total of 1,068,653 surgeries, including 308,810 laparoscopic hysterectomies, 549,959 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, and 209,884 laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. Across the study period, robotic-assisted surgery accounted for 45.6% of hysterectomies, 16.4% of cholecystectomies, and 49.0% of inguinal hernia repairs.

Trends in robotic-assisted surgeries

Robotic adoption increased steadily across all procedures over the study period, though the magnitude of growth varied substantially by operation. Use in hysterectomy rose modestly, increasing from 39.4% in 2018 to 50.6% in 2025 (28.4% relative growth). In contrast, robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair saw more rapid uptake, climbing from 33.4% to 54.8% (64.1% relative increase). The sharpest change occurred in cholecystectomy, where robotic use expanded more than sixfold—from 4.9% to 33.1%—representing a 575.5% relative increase over the study period.

Comorbidities and disease severity

Across all procedures, patients with higher Elixhauser comorbidity scores, a measure of how many chronic health conditions a patient has, were more likely to undergo robotic-assisted surgery. A lower score, such as 0, indicates few or no recorded chronic conditions, while a higher score, such as 11 or more, reflects a greater number of coexisting health conditions.

For hysterectomy, robotic assistance was used in 40.9% of surgeries performed on patients with an Elixhauser comorbidity score less than or equal to 0 and was used in 57.6% of surgeries in patients with an Elixhauser comorbidity score greater than or equal to 11.

Similar, though less pronounced, patterns were observed for cholecystectomy and inguinal hernia repair.

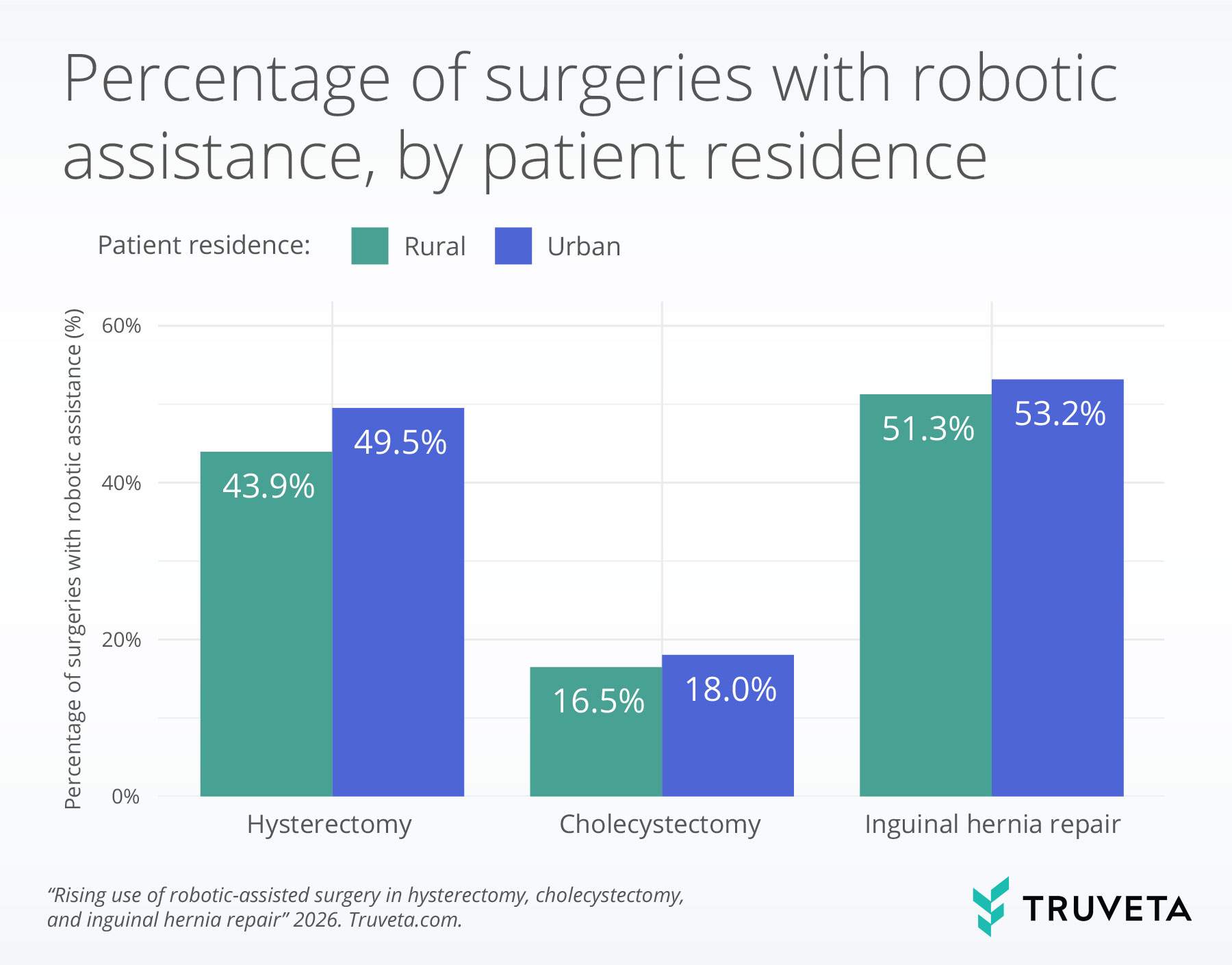

Patient residence

Across all three procedures, robotic assistance was significantly higher among patients living in urban areas compared with those in rural areas.

For hysterectomy, 49.5% of patients living in urban areas received robotic-assisted surgery compared with 43.9% of patients living in rural areas.

In cholecystectomy, 18.0% of patients living in urban areas received robotic-assisted surgery compared with 16.5% of patients living in rural areas.

For inguinal hernia repair, 53.2% of patients living in urban areas received robotic-assisted surgery compared with 51.3% of patients living in rural areas.

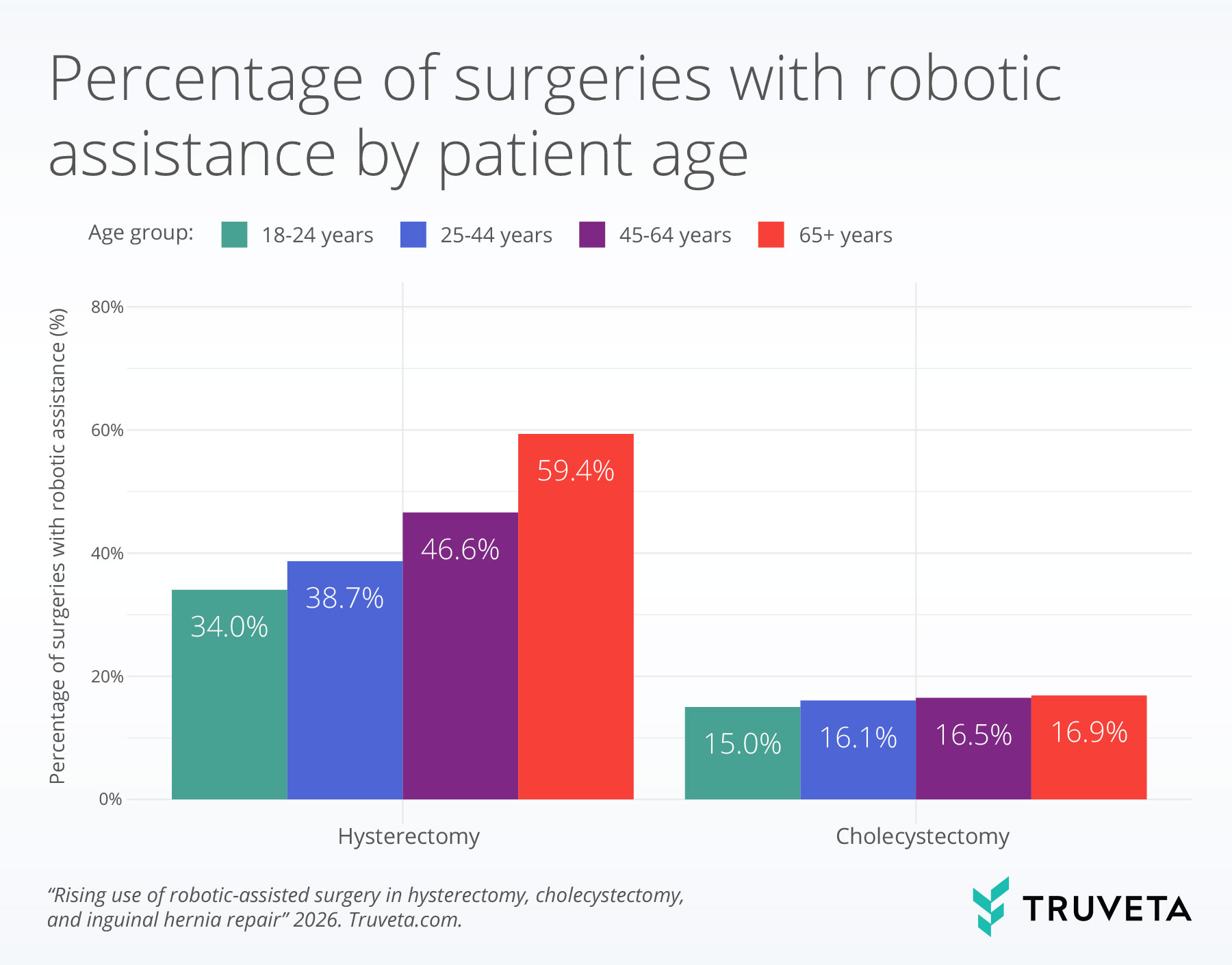

Patient age

Robotic assistance increased significantly with patient age for hysterectomy and cholecystectomy procedures.

For hysterectomy, robotic-assisted surgery increased from 34.0% among patients aged 18–24 years to 59.4% among those aged 65 years and older.

For cholecystectomy, robotic use increased from 15.0% among patients aged 18–24 years to 16.9% among patients aged 65 years and older.

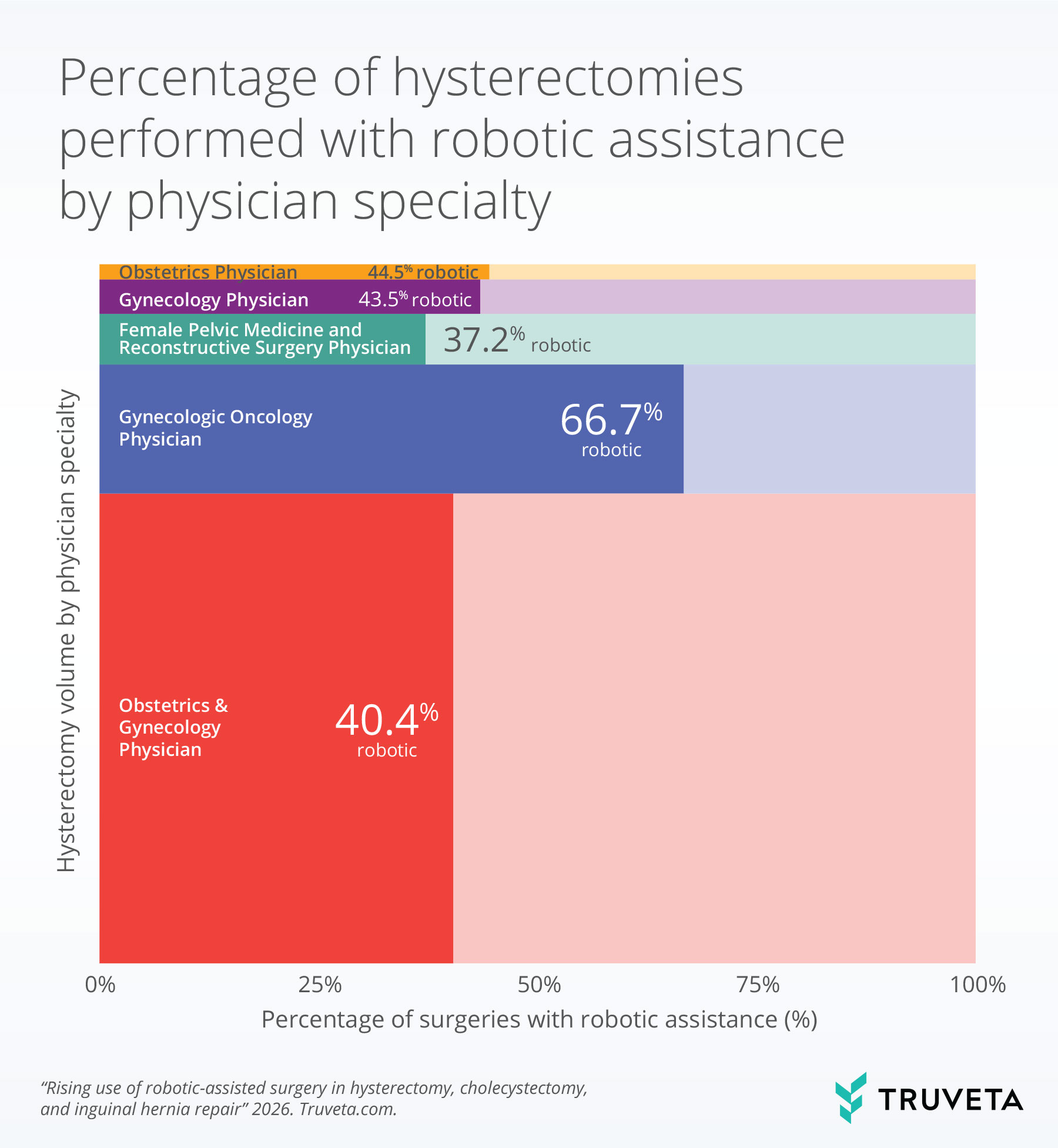

Provider specialty for hysterectomies

Because hysterectomy demonstrated substantial robotic adoption overall, we next examined variation in robotic use for this procedure by physician specialty. Robotic-assisted hysterectomy varied by physician specialty.

Gynecologic oncology physicians had the highest use of robotic assistance, performing 66.7% of hysterectomies with robotic assistance.

Among other specialties, robotic assistance was highest among obstetrics physicians (44.5%), followed by gynecology physicians (43.5%).

Obstetrics and gynecology physicians (40.4%) and female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery physicians (37.2%) had the lowest rates of utilizing robotic assistance while preforming hysterectomies.

The bar width indicates the relative volume of the physician specialty who performed a hysterectomy. The more saturated portion of each bar represents the percentage of physicians who performed a hysterectomy with robotic assistance.

Gynecologic cancer and robotic assistance for hysterectomies

Additional clinical factors were associated with the use of robotic assistance during hysterectomy.

Patients with a history of gynecologic cancer had the highest rates of robotic-assisted hysterectomy (68.8%).

Among other clinical conditions, robotic assistance was highest among patients with a history of uterine prolapse (50.3%) and endometriosis (50.1%).

Robotic assistance was used slightly less frequently but remained common in patients who were overweight or obese (48.3%) and patients with a history of uterine fibroids (47.3%).

Discussion

In this analysis of more than one million laparoscopic procedures performed between 2018 and 2025, we observed substantial growth in the use of robotic-assisted surgery across hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair. The most dramatic relative growth occurred in cholecystectomy, where robotic use expanded more than six-fold. These findings are consistent with prior studies reporting rising adoption of robotic-assisted surgery across multiple surgical specialties (2, 19, 20).

Across all three procedures, robotic-assisted surgery was more frequently used among patients with higher Elixhauser comorbidity scores, indicating that patients with more complex underlying health conditions were more likely to undergo robotic procedures. Patient age was another factor associated with robotic assistance, particularly for hysterectomy and cholecystectomy. This pattern is also consistent with prior studies suggesting that robotic-assisted surgery may be more commonly used in more complex cases where greater visualization or technical precision is required (24–28). In addition, this pattern may also reflect the fact that patients with greater medical complexity are more likely to receive care at centers with greater access to advanced surgical technologies, including robotic platforms (29). Regardless, the consistent association between comorbidity burden and robotic use suggests that adoption is associated with patient clinical risk.

Geographic differences were also apparent. Patients living in urban areas were significantly more likely to receive robotic-assisted surgery than those in rural areas across all procedures. Robotic platforms are more commonly available in large, urban health systems, and rural hospitals may face financial, workforce training, or volume-related barriers to adoption (30, 31). Ongoing advances in robotic technology, including early development of remote and tele-robotic capabilities, could broaden access to specialized surgical care by allowing surgeons to support or perform complex procedures across geographic boundaries (29). As robotic surgery continues to expand, it will be important to monitor how these changes affect rural–urban differences in access to care.

For hysterectomy, we observed notable variation by surgeon specialty and clinical indication. Gynecologic oncologists had the highest rates of robotic-assisted hysterectomy, and patients with a history of gynecologic cancer were more likely to undergo robotic-assisted surgery than those without. This pattern reflects prior work showing higher use of robotic-assisted surgery in gynecologic oncology and among more complex patients (30, 32, 33). It may also be influenced by differences in training and experience with robotic techniques (32, 34, 35).

This study has a few limitations. We relied on procedure codes and robotic device documentation to identify robotic-assisted surgeries, which may vary across institutions. Additionally, while we adjusted for a wide range of patient and provider characteristics, unmeasured factors such as insurance coverage, hospital size, surgical volume, teaching status, and availability of robotic platforms may also influence the decision to use robotic assistance.

This analysis draws on recent real-world data spanning more than one million patients across the US to describe contemporary trends in robotic-assisted surgery as practice patterns continue to evolve. By examining multiple common laparoscopic procedures and variation by patient and provider characteristics, these findings offer insight into how robotic-assisted surgery is currently being used in routine clinical care. As surgical technologies and practice continue to change, analyses using up-to-date, large-scale data can help contextualize how new approaches are adopted in real-world settings.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data accessed on December 12, 2025.

Citations

- M. M. Tiwari, J. F. Reynoso, R. High, A. W. Tsang, D. Oleynikov, Safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of common laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc 25, 1127–1135 (2011).

- K. H. Sheetz, J. Claflin, J. B. Dimick, Trends in the adoption of robotic surgery for common surgical procedures. JAMA Network Open 3, e1918911–e1918911 (2020).

- D. Luchristt, O. Brown, K. Kenton, C. E. Bretschneider, Trends in operative time and outcomes in minimally invasive hysterectomy from 2008 to 2018. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 224, 202-e1 (2021).

- M. Diana, Jjbj. Marescaux, Robotic surgery. Journal of British Surgery 102, e15–e28 (2015).

- D. Sarlos, L. Kots, N. Stevanovic, G. Schaer, Robotic hysterectomy versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: Outcome and cost analyses of a matched case–control study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 150, 92–96 (2010).

- H. Muaddi, M. E. Hafid, W. J. Choi, E. Lillie, C. de Mestral, A. Nathens, T. A. Stukel, P. J. Karanicolas, Clinical Outcomes of Robotic Surgery Compared to Conventional Surgical Approaches (Laparoscopic or Open): A Systematic Overview of Reviews. Annals of Surgery 273, 467 (2021).

- E. J. Charles, J. H. Mehaffey, C. A. Tache-Leon, P. T. Hallowell, R. G. Sawyer, Z. Yang, Inguinal hernia repair: is there a benefit to using the robot? Surg Endosc 32, 2131–2136 (2018).

- R. P. Pasic, J. A. Rizzo, H. Fang, S. Ross, M. Moore, C. Gunnarsson, Comparing Robot-Assisted with Conventional Laparoscopic Hysterectomy: Impact on Cost and Clinical Outcomes. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 17, 730–738 (2010).

- A. Qabbani, O. M. Aboumarzouk, T. ElBakry, A. Al-Ansari, M. S. Elakkad, Robotic inguinal hernia repair: systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ Journal of Surgery 91, 2277–2287 (2021).

- L. Solaini, D. Cavaliere, A. Avanzolini, G. Rocco, G. Ercolani, Robotic versus laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Robotic Surg 16, 775–781 (2022).

- D. S. Strosberg, M. C. Nguyen, P. Muscarella, V. K. Narula, A retrospective comparison of robotic cholecystectomy versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy: operative outcomes and cost analysis. Surg Endosc 31, 1436–1441 (2017).

- A. Tan, H. Ashrafian, A. J. Scott, S. E. Mason, L. Harling, T. Athanasiou, A. Darzi, Robotic surgery: disruptive innovation or unfulfilled promise? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the first 30 years. Surg Endosc 30, 4330–4352 (2016).

- A. VARGHESE, M. DOGLIOLI, A. N. FADER, Updates and Controversies of Robotic-Assisted Surgery in Gynecologic Surgery. Clin Obstet Gynecol 62, 733–748 (2019).

- P. P. Rao, Robotic surgery: new robots and finally some real competition! World J Urol 36, 537–541 (2018).

- A. Sarin, S. Samreen, J. M. Moffett, E. Inga-Zapata, F. Bianco, N. A. Alkhamesi, J. D. Owen, N. Shahi, J. C. DeLong, D. Stefanidis, C. M. Schlachta, P. Sylla, D. E. Azagury, for The SAGES Robotic Platforms Working Group, Upcoming multi-visceral robotic surgery systems: a SAGES review. Surg Endosc 38, 6987–7010 (2024).

- A. Brodie, N. Vasdev, The future of robotic surgery. annals 100, 4–13 (2018).

- E. I. George, T. C. Brand, A. LaPorta, J. Marescaux, R. M. Satava, Origins of Robotic Surgery: From Skepticism to Standard of Care. JSLS 22, e2018.00039 (2018).

- T. Haidegger, S. Speidel, D. Stoyanov, R. M. Satava, Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery—Surgical Robotics in the Data Age. Proceedings of the IEEE 110, 835–846 (2022).

- C. L. Stewart, P. H. G. Ituarte, K. A. Melstrom, S. G. Warner, L. G. Melstrom, L. L. Lai, Y. Fong, Y. Woo, Robotic surgery trends in general surgical oncology from the National Inpatient Sample. Surg Endosc 33, 2591–2601 (2019).

- C. P. Childers, M. Maggard-Gibbons, Trends in the use of robotic-assisted surgery during the COVID 19 pandemic. British Journal of Surgery 108, e330–e331 (2021).

- S. P. Kim, S. A. Boorjian, N. D. Shah, C. J. Weight, J. C. Tilburt, L. C. Han, R. H. Thompson, Q.-D. Trinh, M. Sun, J. P. Moriarty, R. J. Karnes, Disparities in Access to Hospitals with Robotic Surgery for Patients with Prostate Cancer Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy. The Journal of Urology 189, 514–520 (2013).

- L. C. Tatebe, R. Gray, K. Tatebe, F. Garcia, B. Putty, Socioeconomic factors and parity of access to robotic surgery in a county health system. J Robotic Surg 12, 35–41 (2018).

- C. Van Walraven, P. C. Austin, A. Jennings, H. Quan, A. J. Forster, A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Medical care 47, 626–633 (2009).

- C. Andolfi, K. Umanskiy, Current Trends and Perspectives in Robotic Surgery. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques 29, 127–128 (2019).

- M. Song, Q. Liu, H. Guo, Z. Wang, H. Zhang, Global trends and hotspots in robotic surgery over the past decade: a bibliometric and visualized analysis. J Robotic Surg 19, 33 (2024).

- R. K. Chihara, M. P. Kim, E. Y. Chan, Robotic surgery facilitates complex minimally invasive operations. Journal of Thoracic Disease 12, 4606 (2020).

- L. J. Herrinton, T. Raine-Bennett, L. Liu, S. E. Alexeeff, W. Ramos, B. Suh-Burgmann, Outcomes of Robotic Hysterectomy for Treatment of Benign Conditions: Influence of Patient Complexity. Perm J 24, 19.035 (2019).

- D. W. Doo, S. R. Guntupalli, B. R. Corr, J. Sheeder, S. A. Davidson, K. Behbakht, M. J. Jarrett, M. S. Guy, Comparative Surgical Outcomes for Endometrial Cancer Patients 65 Years Old or Older Staged With Robotics or Laparotomy. Ann Surg Oncol 22, 3687–3694 (2015).

- Y. A. Sherif, M. A. Adam, A. Imana, S. Erdene, R. W. Davis, Remote Robotic Surgery and Virtual Education Platforms: How Advanced Surgical Technologies Can Increase Access to Surgical Care in Resource-Limited Settings. Semin Plast Surg 37, 217–222 (2023).

- A. J. B. Smith, A. AlAshqar, K. F. Chaves, M. A. Borahay, Association of demographic, clinical, and hospital-related factors with use of robotic hysterectomy for benign indications: A national database study. Int J Med Robot 16, e2107 (2020).

- E. A. Blake, J. Sheeder, K. Behbakht, S. R. Guntupalli, M. S. Guy, Factors Impacting Use of Robotic Surgery for Treatment of Endometrial Cancer in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 23, 3744–3748 (2016).

- P. T. Ramirez, S. Adams, J. F. Boggess, W. M. Burke, M. M. Frumovitz, G. J. Gardner, L. J. Havrilesky, R. Holloway, M. P. Lowe, J. F. Magrina, Robotic-assisted surgery in gynecologic oncology: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology consensus statement: developed by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Clinical Practice Robotics Task Force, Gynecologic oncology. 124 (2012)pp. 180–184.

- S. H. Bush, S. M. Apte, Robotic-Assisted Surgery in Gynecological Oncology. Cancer Control 22, 307–313 (2015).

- R. D. Shaw, M. A. Eid, J. Bleicher, J. Broecker, B. Caesar, R. Chin, C. Meyer, A. Mitsakos, A. E. Stolarksi, L. Theiss, B. K. Smith, S. J. Ivatury, Current Barriers in Robotic Surgery Training for General Surgery Residents. Journal of Surgical Education 79, 606–613 (2022).

- S. Azadi, I. C. Green, A. Arnold, M. Truong, J. Potts, M. A. Martino, Robotic Surgery: The Impact of Simulation and Other Innovative Platforms on Performance and Training. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 28, 490–495 (2021).