Sign up for a free account to read full studies, with full transparency into methods and results, and experience the power of Truveta Studio

Authors: Brianna M. Goodwin Cartwright, MS ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Patricia J. Rodriguez, PhD MPH ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Samuel Gratzl, PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Charlotte Baker, DrPH MPH CPH ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Duy Do, PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA, Nicholas Stucky, MD PhD ⊕Truveta, Inc, Bellevue, WA

Date: August, 2024

Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 14.8% of the US population. There are known disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of CKD. Of the 14.8% of people in the US with CKD, up to 90% are unaware of the diagnosis. Black and African-American (henceforth referred to as Black) and Hispanic patients are more likely to develop end stage disease (Stage 5) than white patients and are less likely to be able to obtain care that slows the progression of the disease. Approximately 12.4% of US population is identified as Black but 18.6% of CKD patients are Black.

Race is a social construct that was interspersed in some older methods to diagnose CKD. Race affects both the occurrence and the treatment of disease. Particularly relevant to CKD, patients identified as Black were assumed to have greater muscle mass than non-Black patients because of their race but without a scientific basis. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR or GFR) indicates how well the kidneys are functioning. The lower the number, the worse the kidney function. Due to the racial bias about muscle mass and body composition, these older methods – including the 2009 CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation – showed a false level of kidney function for Black patients by multiplying the GFR by 1.159. We found that this led to underdiagnosis in Black patients and their being diagnosed later and at more severe stages. The 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equation removed race and this change improved the time to CKD diagnosis for all patients, especially Black patients. The NKF-ASN Task Force and the KDIGO now recommend using CKD-EPI 2021 (race-free).Among this population, we describe the number of patients with any switching evidence (prescription or dispense of biosimilar) during the time period. Demographic and health characteristics of patients switching were compared to the overall population.

CKD patients are at high risk for hyperkalemia (serum potassium level ≥ 5.0 mmol/L). Hyperkalemia increases risk of arrythmias and cardiac arrest, hospitalization, ED visits, and mortality. Management of hyperkalemia is essential to decrease poor cardiovascular outcomes and allow patients to continue CKD treatment; it includes potassium-lowering drugs such as potassium blockers, sodium bicarbonate, and diuretics.

Objective

To understand if use of the race-free CKD-EPI 2021 delays the time to use of potassium-lowering drugs

Methods

Using a subset of Truveta Data – including conditions, medication requests (e.g., prescriptions), medication dispensing (e.g., fills), social drivers of health (SDOH), and demographics – we identified patients 18 years old and older with a new CKD diagnosis between January 1, 2021 and December 31, 2022 with at least one medical encounter within the 36 months (about 3 years) prior to diagnosis and no medication dispense of potassium binders at or at least one day before diagnosis.

Patients were excluded if they had a missing or unknown race or sex. We also excluded patients if they had a diagnosis of renal failure, polycystic kidney disease, or acute kidney injury (AKI) at or before CKD diagnosis. AKI patients were excluded because of an inability to discern in the data whether 1) AKI occurred because of CKD or whether CKD occurred because of AKI and because 2) patients with AKI could be sicker than other patients that develop CKD.

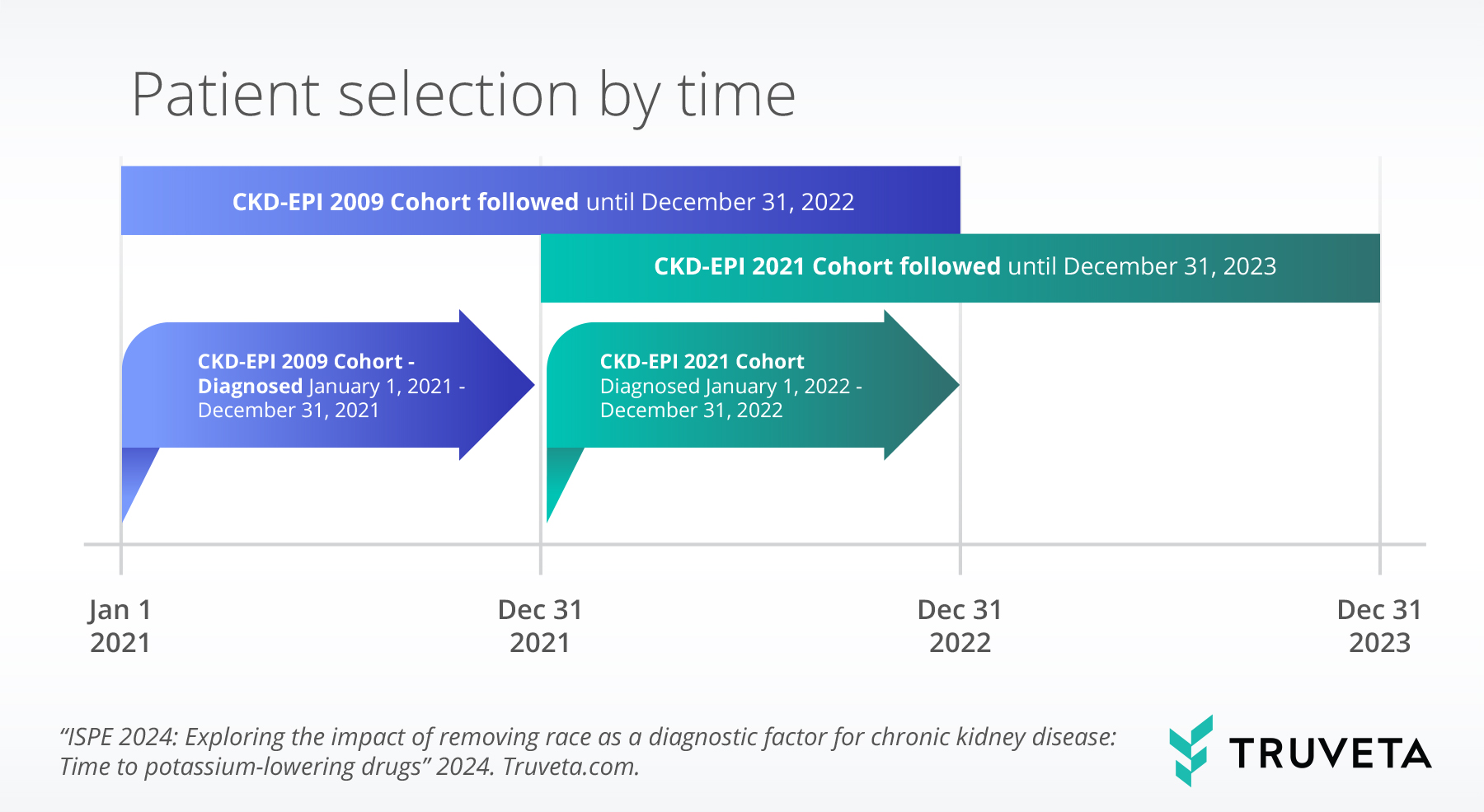

To compare prescription and dispense before and after recommending the removal of race from diagnosing CKD, we used December 31, 2021 as a proxy for the end of the use of the race-inclusive CKD-EPI 2009 equation.

We then created two mutually exclusive cohorts: CKD-EPI 2009 cohort (race-inclusive equation) and CKD-EPI 2021 cohort (race-free equation) based on their date of diagnosis. The CKD-EPI 2009 cohort was diagnosed between January 1, 2021 and December 31, 2021 (inclusive). These patients were diagnosed when the race-based 2009 CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (CKD-EPI 2009) was recommended. The CKD-EPI 2021 cohort was diagnosed between January 1, 2022 and December 31, 2022 (inclusive), when CKD-EPI 2021 was recommended. We then followed patients from the first diagnosis of CKD until a) first occurrence of prescription or dispense of potassium binders, b) last medical encounter recorded in the data, or c) end of a one-year follow-up period, whichever came first. Administrative censoring for patients diagnosed in 2021 was December 31, 2022. Administrative censoring for patients diagnosed in 2022 was December 31, 2023.

We then used Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by cohort and the interaction of cohort and race to describe probability of outcome, as well as Cox proportional hazard models to compare time to first prescription or dispense. We then adjusted for sex, age, race, ethnicity, income, education, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and renal failure.

We identified all conditions using ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM, and SNOMED CT codes. We identified all medications using RxNorm codes.

Results

Before adjustment, use of potassium-lowering drugs differed within race groups and Black patients in both cohorts had higher use than non-Black patients in either cohort.

After adjustment, the hazard of potassium-lowering drug use decreased by 13% after the removal of race from CKD-EPI (AHR 0.87, p<0.0001). There was no statistical difference between race groups (Black patients AHR 0.79, Non-Black patients AHR 0.90, p=0.1). In the same model, use of potassium-lowering drugs was lower for patients that were obese (AHR 0.84; CI 0.79, 0.90) and those that had chronic hypertension (AHR 0.73; CI 0.68, 0.78).

Sign up for a free account to read this full study, with full transparency into methods and results, and experience the power of Truveta Studio