With the NCAA tournament starting this week, we first explored basketball. Truveta employees are in fierce debate over which of their teams will take both the men and women March Madness title this year. We have Duke, University of Kansas, and Virginia Tech alumni on staff, and Gonzaga is always a hometown favorite for many of our Seattle-based employees.

With more than 36 million Americans estimated to be filling out a bracket this week (Statista, 2023), Truveta Research took this as inspiration to dig into Truveta data to see what we could learn about injuries related to basketball, especially for those in the 18-24-year-old age group. We were curious not only about who was experiencing basketball-related injuries, but also for the people who were injured, what body part was injured most often?

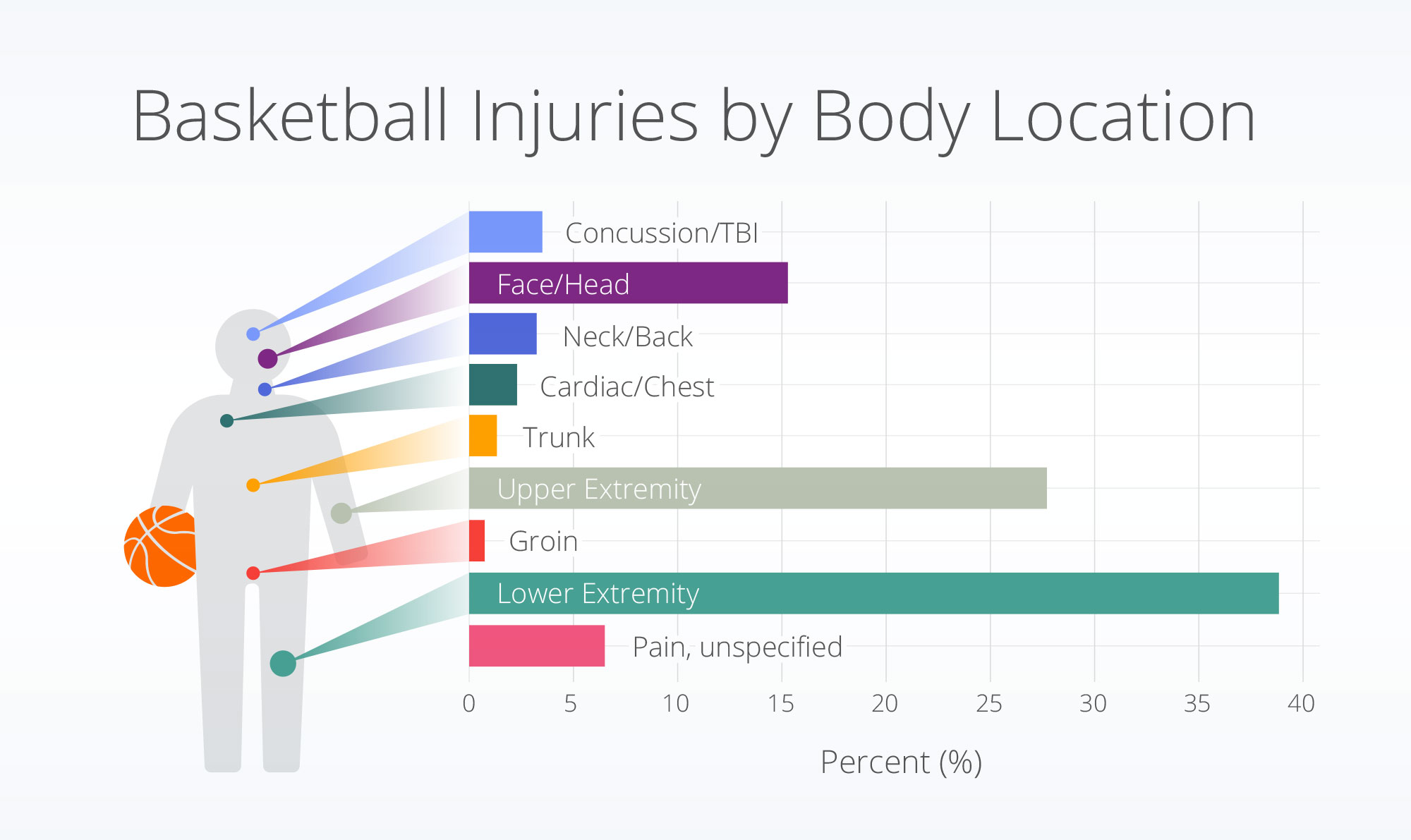

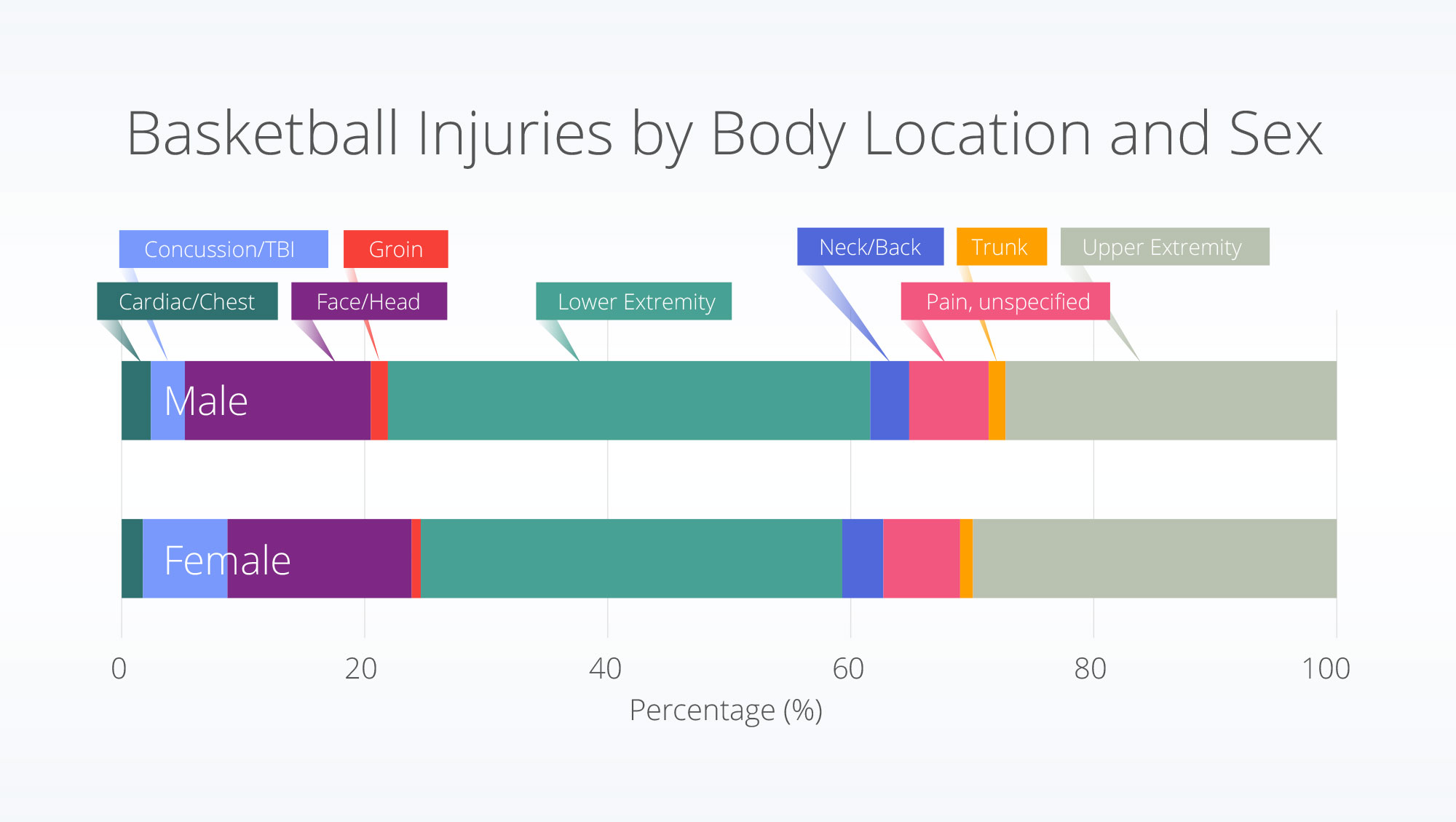

What we learned is of importance to athletic trainers and medical professionals onsite at the NCAA tournaments – lower extremity (legs, ankles, and feet) injuries were the most common injury location among both males and females in the 18–24-year-old age range (same as players in the NCAA tournament). Females in this age range had an increased rate of concussions/traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) compared with males.

Methods

We defined basketball-related injury encounters using a subset of ICD10 codes. Using a subset of Truveta data, we identified over 37,000 people, with over 44,000 basketball-related injury encounters.

We compared the age and sex of those getting injured. We also looked at the location of the encounter to understand how people engaged with the health care system when injuries occurred.

Finally, we classified the body parts that were injured or affected during the basketball injury. We found the diagnostic codes that were associated with the same encounter as the injury and classified them into 13 categories according to injury location (cardiac/chest, concussion/TBI, face/head, groin, lower extremity, neck/back, pain in unspecified location, trunk, upper extremity, other location, unrelated to place of injury on the body). For this analysis we excluded diagnoses that were classified as ‘other location’ or ‘unrelated to place of injury on the body.’ We also excluded a small set of injuries that were associated with multiple sports.

Results

Who made up the injured population?

It’s important to note that there may be differences between the percentage of people who are engaging in sports and who are getting injured (Hanson et al., 2005; Harmon et al., 2018).

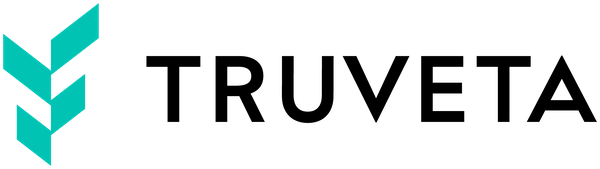

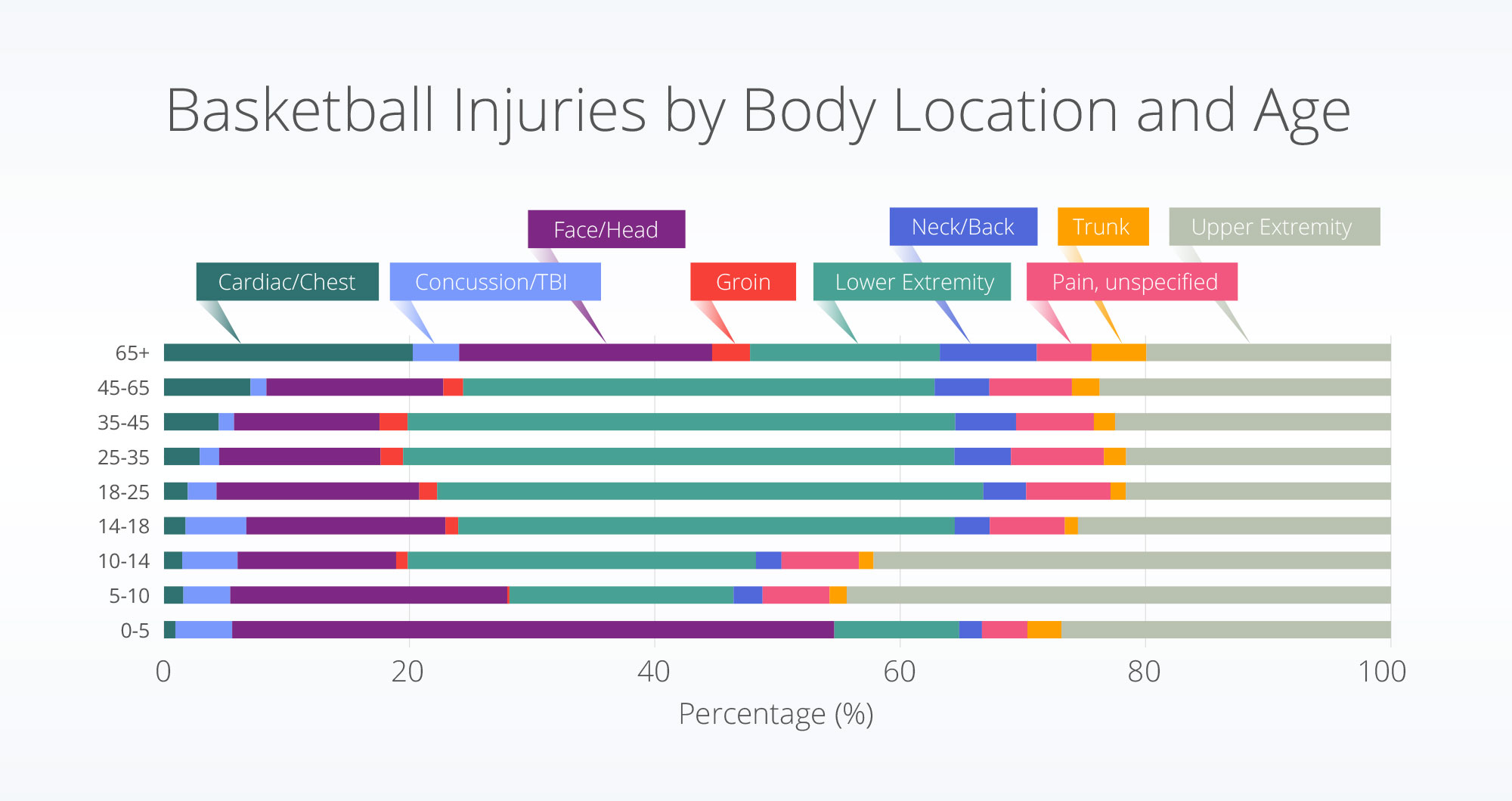

Over half the basketball-related injuries in our population were made up of people between the ages of 14-25. The majority (83.0%) of the population with basketball-related injuries were male. There were differences in the age-distributions of injuries between males and females. Females experience a larger percent of injuries in each age group under 18 (0-5, 5-10, 10-14, and 14-18 years old). About a quarter of the male injuries occurred in the 18–25-year-old age range, which was higher than the percentage of female injuries that occurred in this age range.

When people had basketball-related injuries, did they go to the emergency department?

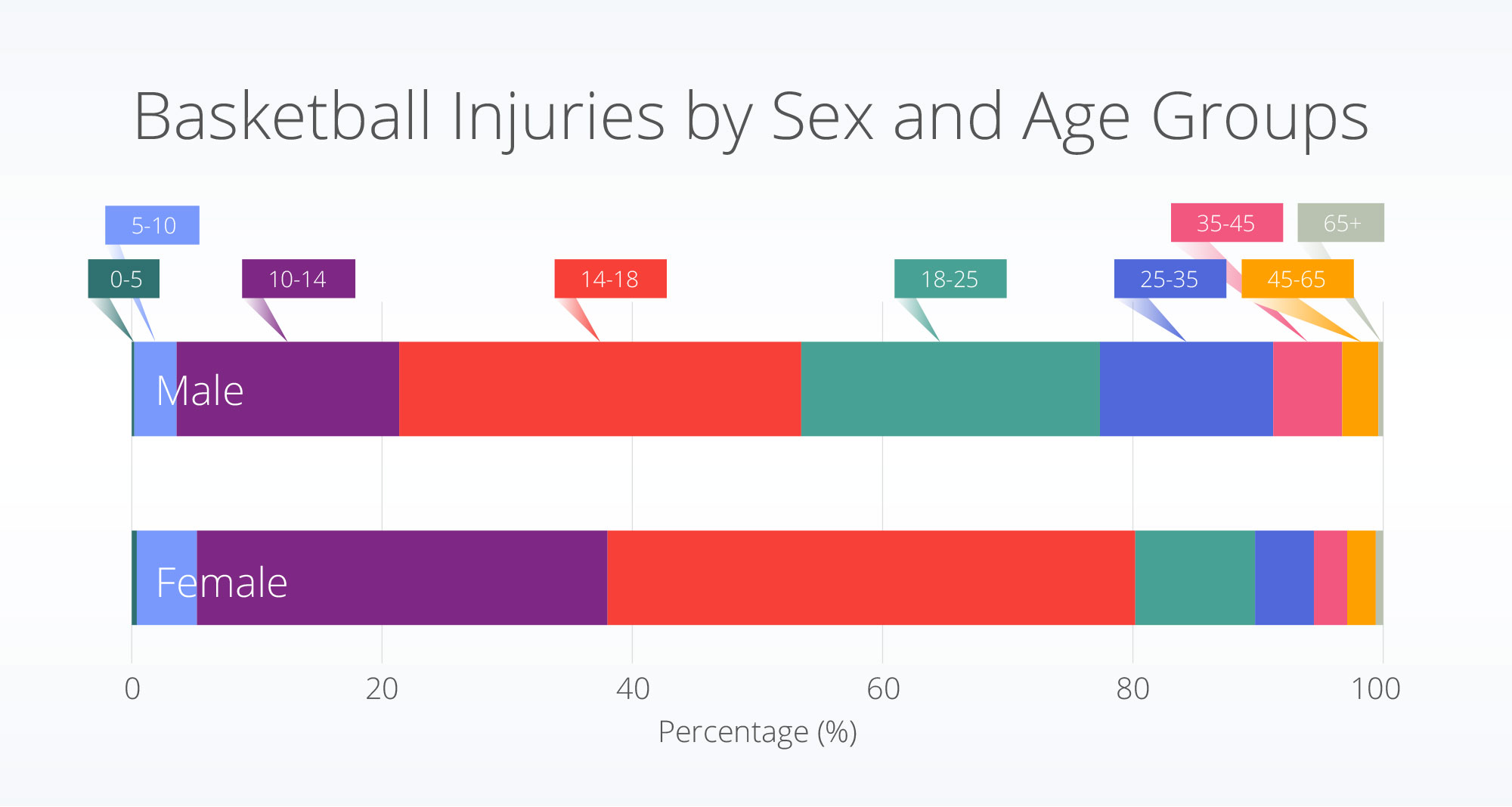

Yes, nearly 85% of injuries in our population resulted in the emergency department visits. This was higher for males compared with females (86.3% compared to 78.8%). Females with basketball injuries had a higher rate of outpatient encounters (14.2% compared to 7.8%).

Emergency department encounters were highest for the 0-5 and 18–25-year-old populations. Inpatient encounters were highest among the 65 and older population. The results for both the oldest and youngest age groups should be interpreted with caution as they represent a small number of overall patients with basketball-related injuries.

What body part is injured?

Most basketball injuries were associated with the lower extremities (38%) and upper extremities (27.7%).

Discussion

With 25% of adults playing sports across the US and an even larger population of children playing sports, studying the injuries associated with sports is important (Black et al., 2022; Harvard T.H. Chan, 2015). Not only does understanding who has been affected by injuries help to inform whether additional safety rules are needed, but understanding the body part affected may also impact clinical treatment programs.

In the population of people experiencing basketball-related injuries, we saw that nearly a quarter of the males experiencing injuries were within the 18-24 age range (age of NCAA tournament players). We also saw this population of males experienced the highest percentage of injuries in their lower extremity. However, with females, we saw an increase in concussions for this age group. Athletic trainers and medical staff should be prepared for these types of injuries during the men’s and women’s NCAA tournaments.

As with any analysis, there are limitations associated with this analysis. First, to be counted as a basketball-related injury, the person had to have an encounter within the hospital system. Injuries that did not include a visit within a hospital system were not captured in our analysis. Further, multiple body parts could be included for one person/injury. To account for this, we counted each body part that was injured but did not explore different injury combinations. Additionally, we classified basketball-related injuries based on the existence of a subset of ICD10 codes related to basketball. If a physician did not use these codes, the injury would not be captured within these data. Finally, no statistical analyses were conducted to test for differences between groups or account for the population who was playing basketball. In this study, we describe the differences within a population with basketball-related injuries, but additional research would be needed to take into account the incidence amongst a population who plays basketball and test for significance.

With every insight, we attempt to answer a series of questions, which, like any research, always generates more questions and hypotheses. This insight generated questions about other sport-related injuries – do we see similar injury profiles for other sports such as baseball and soccer? For those who experience multiple injuries, how are they different than people who only have one injury? Look for upcoming insights in which we continue to explore injuries for different sports.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data pulled January 11, 2023.

References

Black, L. I., Terlizzi, E. P., & Vahratian, A. (2022, August). Organized Sports Participation Among Children Aged 6–17 Years: United States, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics Home. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db441.htm

Hanson, D., Hanson, J., Vardon, P., McFarlane, K., Lloyd, J., Muller, R., & Durrheim, D. (2005). The injury iceberg: An ecological approach to planning sustainable community safety interventions. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 16(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE05005

Harmon, K. J., Proescholdbell, S. K., Register-Mihalik, J., Richardson, D. B., Waller, A. E., & Marshall, S. W. (2018). Characteristics of sports and recreation-related emergency department visits among school-age children and youth in North Carolina, 2010–2014. Injury Epidemiology, 5(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-018-0152-0

Harvard T.H. Chan. (2015, June 15). Poll: Three in four adults played sports when they were younger, but only one in four still play. Harvard T.H. Chan, School of Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/poll-many-adults-played-sports-when-young-but-few-still-play/

Statista. (2023). Estimated number of adults that intend to fill out a bracket during March Madness in the United States in 2019 and 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1223099/bracket-march-madness-intention/