Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a common disease that causes narrowing of the arteries in the extremities. The lifetime risk for Americans varies between 19-30% [1]. Many studies have shown that PAD disproportionately affects both Black or African American (henceforth referred to as Black) and Hispanic or Latino individuals; further, these groups experience worse outcomes (including amputation) compared to white and non-Hispanic or Latino individuals [1-4].

As part of PAD Awareness Month, we investigated disparities in the frequency of common procedures used to treat PAD, known as endovascular (or minimally invasive) revascularization, and the associated outcomes. Revascularization is used to open the artery and improve blood flow to the areas beyond the narrowed artery. As part of this procedure, a small balloon is inflated within the artery to open the narrowed area. Alternatively, a stent, or small metal scaffold device, may also be placed to help keep the artery open for longer periods of time. Newer designs of both balloons and stents include a drug coating to prevent the re-narrowing of the artery once the balloon is removed or following the placement of the stent (called restenosis).

Previous studies have shown disparities in outcomes following revascularization (such as lower-limb amputation and death) by race and sex [5-6]. Many studies have emphasized the need for additional modern data with larger sample sizes to understand disparities in care by procedure type and associated adverse outcomes (such as lower-limb amputation, inpatient readmissions, and additional revascularization procedures) for the PAD population. Large national studies to understand racial and ethnic disparities in those who receive drug-eluting vs. bare stents and balloons have been conducted for the coronary artery disease (CAD) population [7]. Within the PAD population, while studies have been conducted to understand disparities in revascularization type, to the best of our knowledge, previous studies have been limited in terms of geographic region, sample size, timeliness of the data, and association between type of revascularization and outcome based on race, sex, and ethnicity [8].

Due to the small sample sizes observed in previous literature and the timeliness of Truveta data, we wanted to learn more about the PAD population, such as who received revascularization procedures, whether disparities exist among the patients who received drug-coated vs. bare stents and balloons, and whether there were differences in adverse outcomes across the different technologies used.

As a result of this analysis, we found that Black patients with PAD have lower rates of revascularization procedures and receive drug-eluting stents at lower rates when compared to their white counterparts with PAD. We also found that Hispanic or Latino patients with PAD have lower rates of revascularization procedures and use of drug-eluting stents than non-Hispanic or Latino individuals. Given published evidence for better outcomes when drug-eluting devices are used [10-14], this suggests Black and Hispanic or Latino groups may be receiving effective treatments at lower rates than white and non-Hispanic or Latino groups, respectively.

Methods

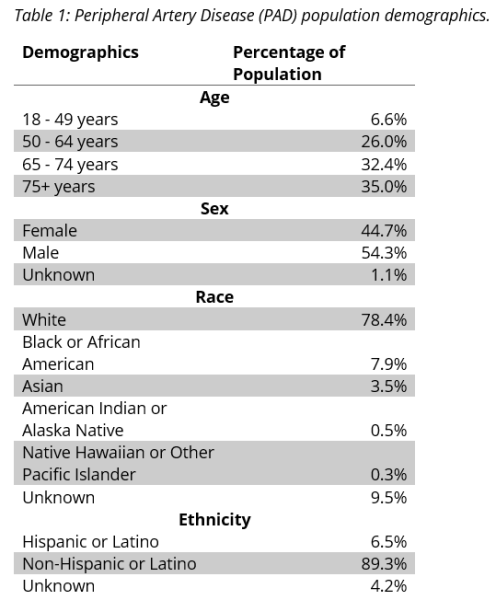

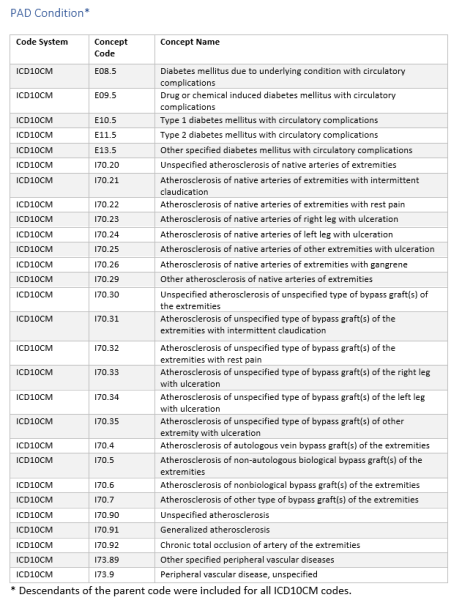

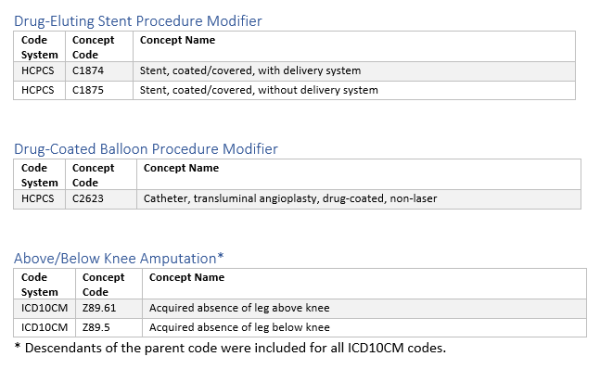

Using a subset of Truveta data, we identified people diagnosed with PAD (Table 1). The diagnostic codes used to identify PAD patients are provided in the supplement. The population resulted in over 455,000 individuals with PAD.

We asked two questions of the PAD population:

- Of the individuals who underwent revascularization procedures, were there differences in the use of drug-eluting stents and drug-coated balloons versus bare metal stents and bare balloons across demographic groups?

- Of the individuals who underwent revascularization procedures, were there differences in the rates of three adverse outcomes by revascularization device?

- Lower-limb amputation: New below-knee and above-knee amputation within a year following the revascularization encounter

- 30-day all-cause re-admission: Inpatient admission within 30 days following the revascularization encounter

- One-year repeat revascularization: Another revascularization procedure within one year following the index revascularization encounter

Revascularization procedure, type of stent, and adverse revascularization outcomes were based on a variety of CPT, HCPCS, and ICD10 codes provided in the supplement.

Results

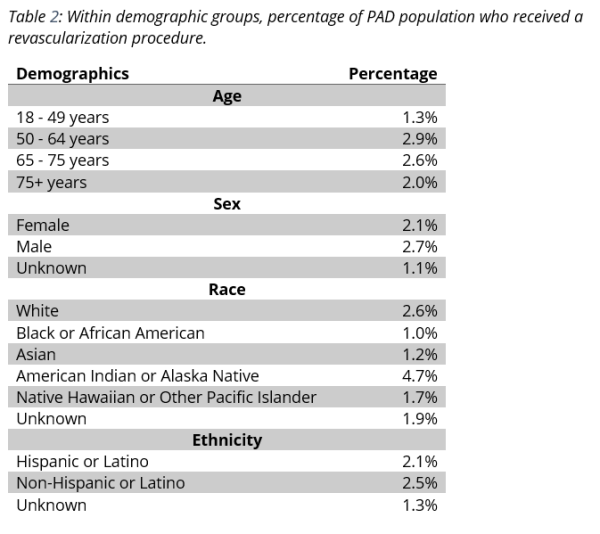

Of those diagnosed with PAD, 2.4% (nearly 11,000) underwent a revascularization procedure. The difference across demographic groups is shown in Table 2.

Differences in treatments across demographic groups

Age

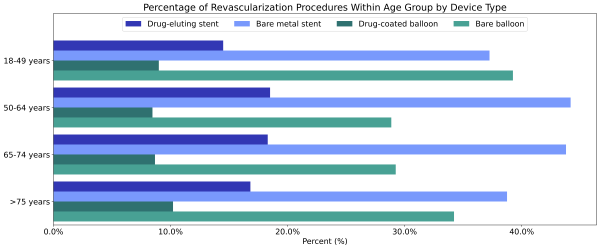

Individuals with PAD who were between the ages of 50 – 64 (2.9%) and 64 – 74 (2.6%) were most likely to receive a revascularization procedure than other age groups. Individuals over 75 and between 18 – 49 received bare balloons at higher rates than in other age groups. The rates of drug-coated balloon use were similar between all adult age groups; however, those age 18-50 received drug-eluting stents less often than other age groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of revascularization procedures within each age group by device type.

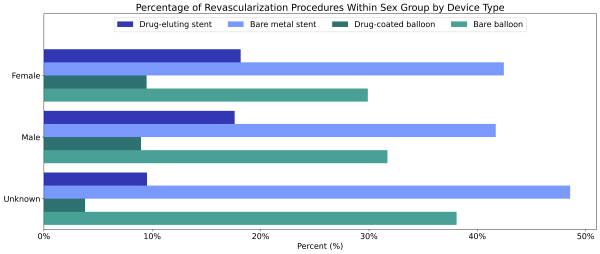

Sex

Females diagnosed with PAD were less likely to receive a revascularization procedure than males diagnosed with PAD (2.1% vs 2.7%, Table 2). However, of individuals who had a revascularization procedure, females received a drug-eluting stent (21.6%) or a drug-coated balloon angioplasty (11.2%) at similar rates to males (20.7% and 10.5%, respectively, Figure 2). The unknowns in this report either indicate the value was not included in the individual’s electronic health record or that it was excluded from the data to protect an individual’s identity as a part of Truveta’s commitment to privacy [9].

Figure 2: Percentage of revascularization procedures among males and females by device type.

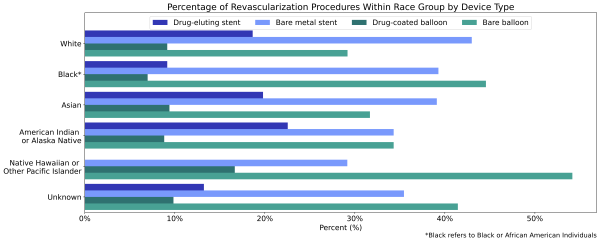

Race

Black (1.0%) and Asian (1.2%) patients diagnosed with PAD were less likely to receive any revascularization procedure compared to white patients (2.6%) diagnosed with PAD (Table 2). American Indian or Alaska Native patients were more likely to receive a revascularization procedure than white patients (4.7% vs 2.6%). A higher percentage of all non-white race groups who received a revascularization procedure received a bare device compared to white individuals (Figure 3). Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander and Black individuals received bare devices at the highest rates. Again, the unknowns in this report either indicate the value was not included in the individual’s electronic health record or that it was excluded from the data to protect an individual’s identity as a part of Truveta’s commitment to privacy [9].

Figure 3: Percentage of revascularization procedures within each race group by device type.

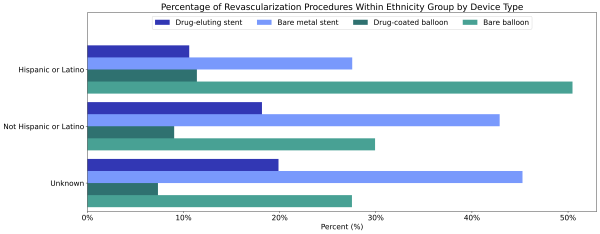

Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino patients diagnosed with PAD were less likely to receive a revascularization procedure than non-Hispanic or Latino patients diagnosed with PAD (2.1% vs 2.5%). When Hispanic or Latino patients did have a revascularization procedure, they were less likely to receive a drug-eluting stent (12.7%), but more likely to receive a drug-coated balloon angioplasty (13.5%) than non-Hispanic or Latino patients (21.4% and 10.6%, Figure 4).

Figure 4: Percentage of revascularization procedures within each ethnicity group by device type.

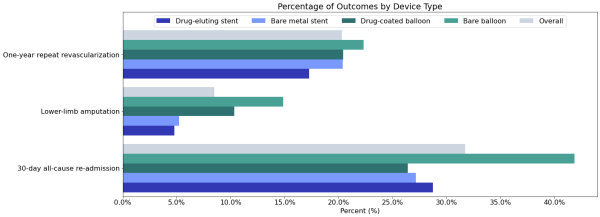

Differences in revascularization outcomes

Figure 5 shows the percentage of the population who experienced adverse outcomes by revascularization type.

Figure 5: Percentage of population who had one of three adverse outcomes following a revascularization procedure.

Lower-limb amputation

Overall, 8.5% of patients in this cohort who underwent a revascularization procedure suffered a lower limb amputation within one year. The highest rates occurred for individuals who received a bare balloon (14.9%), and the lowest rates occurred for those who received drug-eluting stents (4.8%).

30-day all-cause re-admission

Overall, 31.7% of people who had a revascularization procedure were re-hospitalized within 30 days of the procedure. This occurred most frequently for patients who were initially treated with bare balloons (41.9%).

One-year repeat revascularization

Overall, 20.3% of people who had a revascularization procedure had another revascularization procedure within one year of the initial procedure. This occurred most frequently for those whose index revascularization was with bare balloons (22.3%); however, repeat procedures were provided for 17.3% of patients for all procedure types.

Discussion

Based upon prior studies [2, 3, 4] showing disparities in treatment and outcomes in PAD, we expected to find that Black and Hispanic or Latino individuals underwent revascularization at lower rates than whites. These expectations were supported by the results presented here for rates of procedures for Black and Asian patients. They also were seen for Hispanic or Latino patients when compared with non-Hispanic or Latino patients. American Indians or Alaska Native patients were unexpectedly more likely to have undergone revascularization procedures than white patients. This result should be interpreted with caution, as no methods to compare the population in this study to the US national population was conducted in this study, and a limited sample size for American Indians or Alaska Native patients may affect these results.

Published literature has indicated that drug-coated devices have improved outcomes when compared with non-drug coated alternatives [10-14]. Additionally, race was found to be a larger predictor of revascularization or amputation than insurance or socioeconomic status [2]. With that in mind, we expected Black patients and other historically marginalized racial groups to be less likely to receive superior outcome endovascular devices such as a drug-eluting stent and drug-coated balloon. This was true of Black patients with drug-eluting stents, but not drug-coated balloons. Other historically marginalized racial groups did not show this trend. Hispanic or Latino patients also received bare metal stents and bare balloons at higher rates compared with the non-Hispanic or Latino patient group.

Finally, and most importantly, this analysis demonstrated amputation risks as higher for patients initially treated with bare metal stents and bare balloons compared to drug-coated devices. One-year repeat revascularization rates were lowest for drug eluting stents and similar for other devices. Interestingly, this benefit of drug-eluting devices was not seen in 30-day all-cause re-admission rates.

As with any analysis, this analysis has limitations. First, we looked at raw data and did not adjust for comorbidities such as diabetes, which have been shown to influence outcomes and are more prevalent in certain populations. Second, while this is a large sample, it does not include all patients in the US; there is a potential for sampling bias where certain groups may be over- or underrepresented (e.g., certain rural regions). Also, outcomes in this study were not directly linked to the revascularization procedure; therefore, we can’t say if an amputation, hospitalization, or subsequent revascularization following a procedure was directly related to the initial revascularization or a different root cause. Finally, this analysis did not include underlying socioeconomic measures, such as income or housing instability, which have been shown to influence a variety of medical outcomes.

In the future, we plan to build upon this analysis by exploring certain demographics like age in greater detail, adjusting for comorbidities, and incorporating social determinants of health (SDOH) data. Additionally, adding more device-level data, such as price, in combination with the SDOH data would be interesting to further understand the disparities in device type and outcome.

Conclusion

Truveta data shows that there are disparities in both the patients who received PAD treatment with revascularization and the specific devices used in revascularization. Black and Hispanic or Latino individuals have lower rates of revascularization and drug-eluting stents than white and non-Hispanic or Latino individuals, respectively. Given published evidence for better outcomes with drug-eluting devices [10-14], this suggests they may be receiving optimal therapy at lower rates.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating. These findings are consistent with data from August 24, 2022.

Citations

- Virani, Salim S., et al. “Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association.” Circulation8 (2021): e254-e743. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950

- Durazzo, Tyler S., Stanley Frencher, and Richard Gusberg. “Influence of race on the management of lower extremity ischemia: revascularization vs amputation.” JAMA surgery7 (2013): 617-623. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/1669979

- Guadagnoli, Edward, et al. “The influence of race on the use of surgical procedures for treatment of peripheral vascular disease of the lower extremities.” Archives of Surgery4 (1995): 381-386. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/article-abstract/596176

- Eslami, Mohammad H., Maksim Zayaruzny, and Gordon A. Fitzgerald. “The adverse effects of race, insurance status, and low income on the rate of amputation in patients presenting with lower extremity ischemia.” Journal of vascular surgery1 (2007): 55-59. https://www.jvascsurg.org/article/S0741-5214(06)01749-6/fulltext

- Mustapha, Jihad A., George L. Adams, and Ehrin J. Armstrong. “Racial Disparities in Risk for Major Amputation or Death After Endovascular Interventions for Peripheral Artery Disease: A LIBERTY 360 Study.” (2021).

- Behrendt, Christian-Alexander, et al. “Sex disparities in long-term mortality after paclitaxel exposure in patients with peripheral artery disease: a nationwide claims-based cohort study.” Journal of clinical medicine 10.13 (2021): 2978.

- Kumar, Robert S., et al. “Effect of race and ethnicity on outcomes with drug-eluting and bare metal stents: results in 423 965 patients in the linked National Cardiovascular Data Registry and centers for Medicare & Medicaid services payer databases.” Circulation13 (2013): 1395-1403.

- Loja, Melissa N., et al. “Racial disparities in outcomes of endovascular procedures for peripheral arterial disease: an evaluation of California hospitals, 2005–2009.” Annals of vascular surgery5 (2015): 950-959.

- Our Approach to protecting Patient Privacy. Spring 2022. Truveta’s Approach to Patient Privacy. https://resources.truveta.com/patient-privacy?hsLang=en

- Rastan, Aljoscha, et al. “Sirolimus-eluting stents for treatment of infrapopliteal arteries reduce clinical event rate compared to bare-metal stents: long-term results from a randomized trial.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology7 (2012): 587-591. https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.035

- Tepe, Gunnar, et al. “Drug-coated balloon versus standard percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for the treatment of superficial femoral and popliteal peripheral artery disease: 12-month results from the IN. PACT SFA randomized trial.” Circulation5 (2015): 495-502. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011004

- Bosiers, Marc, et al. “Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting versus bare-metal stents in patients with critical limb ischemia and infrapopliteal arterial occlusive disease.” Journal of vascular surgery2 (2012): 390-398. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0741521411020787

- Steiner, Sabine, et al. “COMPARE: prospective, randomized, non-inferiority trial of high-vs. low-dose paclitaxel drug-coated balloons for femoropopliteal interventions.” European heart journal 41.27 (2020): 2541-2552. COMPARE: prospective, randomized, non-inferiority trial of high- vs. low-dose paclitaxel drug-coated balloons for femoropopliteal interventions | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

- Gray, William A., et al. “A polymer-coated, paclitaxel-eluting stent (Eluvia) versus a polymer-free, paclitaxel-coated stent (Zilver PTX) for endovascular femoropopliteal intervention (IMPERIAL): a randomised, non-inferiority trial.” The Lancet 392.10157 (2018): 1541-1551. A polymer-coated, paclitaxel-eluting stent (Eluvia) versus a polymer-free, paclitaxel-coated stent (Zilver PTX) for endovascular femoropopliteal intervention (IMPERIAL): a randomised, non-inferiority trial – ScienceDirect

Supplement Data Definitions

Truveta is a collective of US health systems with a shared vision of saving lives with data. Through partnerships with 24 innovative health system members, Truveta offers innovative solutions to enable researchers find cures faster, empower every clinician to be an expert, and help families make the most informed decisions about their care. Truveta’s data is licensed for healthcare research, not targeted advertising. To learn more, follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter, and sign up for our newsletter.