The pandemic has fundamentally changed the way we live. For many of us, it has also changed our interactions with the world around us. Previous reports have shown how living through the pandemic has impacted mental health [1,2], including how a COVID-19 diagnosis impacts mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety [3]. Even before the pandemic, adolescents were at high risk for mental health-related diagnoses [4]. During the pandemic this has only intensified; in late 2021 the US Surgeon General issued an advisory about the mental health status of children, adolescents, and young adults and provided specific recommendations to decrease the effects of the pandemic on this group’s mental wellbeing.

Some diagnosed with COVID-19 have a variety of post-COVID-19 symptoms, commonly referred to as long COVID. Symptoms vary and can include cardiovascular, coagulation and hematologic, gastrointestinal, kidney, mental health, metabolic, musculoskeletal, and neurologic disorders [5]. It’s estimated that 1 in 5 adults experience some long COVID symptoms [6], and as such researchers are actively trying to understand the risk factors and downstream effects. Given the potential dire outcomes from mental health disorders, it is important to understand mental health outcomes as the pandemic persists and the effects of long COVID are becoming apparent.

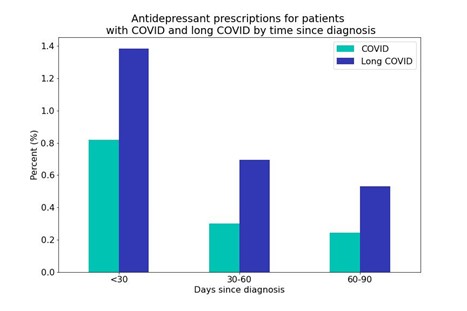

The Truveta Research team was curious to explore the incidence of a first-time antidepressant prescription within 30, 60, and 90 days of those diagnosed with long COVID. As a comparison, we also looked at trends in first-time antidepressant prescriptions for those who experienced a first-time COVID infection but were not diagnosed with long COVID. We explored a subset of the Truveta dataset to answer these questions.

We found that it’s likely that long COVID not only affects people physically, but also mentally. Adults with long COVID were nearly two times more likely to receive a first-time antidepressant prescription in the first 90 days following a diagnosis (2.6%) than someone with a COVID infection (1.4%). In adolescents, those diagnosed with long COVID are are nearly 2 times more likely to receive a first-time antidepressant prescription in the first 90 days following their diagnosis (5.4%) than someone with a COVID infection (2.8%).

Methods

Using a subset of the Truveta dataset, we identified COVID and long COVID populations. The COVID population was defined as the first COVID-19 diagnostic code or a positive lab test for those 18 years or older and those aged 12-17 between May 1, 2020 and July 10, 2022. Individuals were excluded from the COVID population if they had a long COVID diagnosis. The long COVID population consisted of individuals over 18 or between 12-17-years-old who had a long COVID diagnosis (ICD10 U09.9: “Post COVID-19 condition, unspecified” or SNOMED CT:1119303003, “Post-acute COVID-19”) between May 1, 2020 and July 10, 2022.

We excluded anyone who had an antidepressant prescription before the COVID diagnosis/lab test (COVID population) or long COVID diagnosis (long COVID population). Antidepression drugs included SSRIs and SNRIs (Fluoxetine, Paroxetine, Sertraline, Citalopram, Escitalopram, Fluvoxamine, Duloxetine, and Venlafaxine). This resulted in adult cohorts of over 1.3 million and 19,000 patients who had COVID or a long COVID diagnosis, respectively, with no previous antidepression prescriptions. The adolescent populations consisted of 88,000 12-17-year-olds with COVID and nearly 600 12-17-year-olds with long COVID, without a previous antidepression prescription. We will refer to these populations as the COVID and long COVID populations.

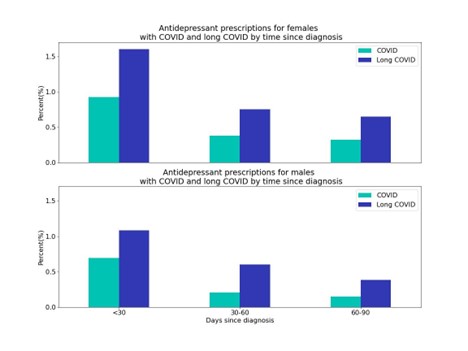

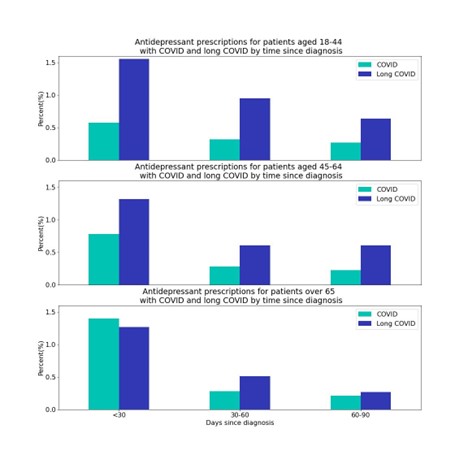

We looked at the rate of first-time antidepression prescriptions within the first 30, 60, and 90 days for both populations. We further looked at differences by sex and age groups (18-44, 45-64, and over 65 years old).

Results

Adults:

Our results show 1 in 73 COVID patients (1.4%) and 1 in 38 long COVID diagnosed patients (2.6%) are receiving a first-time antidepressant prescription within 90 days of their diagnosis. Over half of the first-time prescriptions (53%, or 1.4% overall) for patients with long COVID occur within the first 30-days following the diagnosis. Within the first 90 days, the long COVID population was nearly twice as likely to receive an antidepressant prescription than the COVID population.

For both the COVID and long COVID populations, women are prescribed first-time antidepressants at a higher rate (COVID = 1.6%; long COVID = 3.0%) than men (COVID = 1.1%; long COVID = 2.1%). This trend is consistent across all time periods. We have previously reported that women are also more likely to be diagnosed with long COVID.

For the long COVID population those aged 18-44 are more likely to get a first-time prescription (3.1%) compared with those 45-64 (2.5%) and over 65 (2.0%) within the first 90-days of the diagnosis. For those with a long COVID diagnosis, 18–44-year-olds and 45-64-year-olds have 2.7-times and 2-times the rate of first-time antidepressant prescriptions within the first 90 days, respectively. The long COVID population over 65 has 1.1-times the rate as the COVID population within the first 90 days, and the COVID population had a higher first-time antidepressant prescription rate during the first 30 days following diagnosis.

Adolescents:

For the adolescent population we see 1 in 19 (5.4%) long COVID diagnosed adolescent patients are receiving a first-time antidepressant prescription within 90 days of diagnosis. This is nearly 2 times the rate of the COVID population, where 1 in 36 (2.8%) adolescents are prescribed first-time antidepressant prescriptions.

Both COVID (4.0%) and long COVID (7.3%) female adolescents are over 2.4-times more likely to be prescribed antidepressants within 90 days than male adolescents (COVID: 1.5%; long COVID: 3.0%). This first-time prescription occurs at nearly 2 times the rate for female adolescents with long COVID compared to COVID. Nearly 1 in 14 female adolescents are receiving a prescription within 90 days of a long COVID diagnosis.

Discussion

Adults and adolescents who have never received an antidepression prescription are receiving one following a long COVID diagnosis and at greater rates than those diagnosed with COVID. For both adolescents and adults, females are more likely to receive a first-time prescription than males.

These results prompt further research questions: Are these antidepressant prescriptions the result of social factors such as isolation or living with long COVID symptoms for an extended period of time, or due to changes in underlying brain physiology, or both? Why do we see differences in prescribing practices between sexes across multiple age groups? How does calendar time in the pandemic affect these results, as long COVID diagnoses always occur after a COVID diagnosis?

Limitations:

There are a few limitations associated with the results presented here. Drug prescriptions were included regardless of status and therefore do not indicate the person filled the prescription or took the medication as prescribed. Diagnoses and symptoms associated with long COVID are still actively being defined. We assumed that long COVID was defined by the presence of one of two diagnostic codes physicians used when long COVID symptoms are seen in patients. We did not confirm individuals in our long COVID population had a previous positive COVID-19 test, as these are not always captured in the medical record (e.g., at-home rapid tests). However, if an individual received a long COVID diagnosis, they presumably had a previous COVID positive diagnosis or positive test. For the COVID population we may miss those with tests not reported in their health record (e.g., at-home rapid tests). The COVID lab/diagnosis, long COVID diagnosis, and antidepressant prescriptions (before or after the long COVID diagnosis) all needed to occur within a Truveta health system for them to be captured within our analyses. Finally, the analyses presented here did not adjust for differences in demographics between our population and the general public. We used a COVID population to give reference to the long COVID population, however we did not match patient demographics between the groups.

Overall, our results emphasize that as clinicians and researchers aim to further understand the complexities related to long COVID, healthcare providers must be acutely aware of their patients’ mental health.

These are preliminary research findings and not peer reviewed. Data are constantly changing and updating, but are consistent with data pulled July 20, 2022.

Citations

[1] Panchal, Urvashi, et al. “The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review.” European child & adolescent psychiatry (2021): 1-27.

[2] O’Connor, Rory C., et al. “Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study.” The British journal of psychiatry 218.6 (2021): 326-333.

[3] Xie, Yan, Evan Xu, and Ziyad Al-Aly. “Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study.” bmj 376 (2022).

[4] Avenevoli, Shelli, et al. “Mental health surveillance among children–United States, 2005-2011.” (2013).

[5] Al-Aly, Ziyad, Benjamin Bowe, and Yan Xie. “Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Nature Medicine (2022): 1-7.

[6] Bull-Otterson L, Baca S, Saydah S, et al. Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years — United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:713–717. DOI: